A Golden Age?

1st February 2018Nostalgia isn’t history; it’s too caught up with sentiment and rose-tinted recollections to let the facts and diligent research get in the way. So, forgive me if accuracy and well-grounded judgement are casualties in my trip down memory lane to an age or at least a time which for me was and still is golden. As The Good Book says, giants walked on the earth in those days. And please don’t think I am setting out to brag; it just so happens that I was fortunate enough to have experienced a wonderfully rich period of jazz, and only desperate people brag about sheer good fortune.

From the time in my early teens, that’s about 1955, when I first began to think of myself as a fledgling jazz fan, for a period of nine or ten years, I was privileged to hear some of the greatest jazz musicians the world has ever known. During the same period there were some musicians of similar status that I could have heard, but, much to my regret and for reasons that have now drifted from memory, I never did.

Louis Armstrong

One of the very first major jazz concerts I attended featured the man who transformed jazz in the 1920s and who, jazz historians would have us believe, almost single-handedly invented swing, Louis Armstrong. Armstrong, still playing with great power and panache, was appearing with his All Stars, a group that included such stalwarts as Trummy Young, Peanuts Hucko, Arvell Shaw and Billy Kyle. A little while later, I saw another New Orleans veteran, Kid Ory, in the company of that extraordinary trumpeter, Henry ‘Red’ Allen Jr. For some reason that I still can’t explain, I can’t add Sidney Bechet to the list of outstanding veterans that I heard. I suspect that if Bechet had spent more time in America in the 1920s, he would have been a rival to Armstrong, but places new always attracted jazz’s first saxophone superstar. Regrettably, when Bechet toured the UK with Humphrey Lyttelton in the 1950s, I never got to see him, and by the end of the decade this musical giant was sadly no longer with us. I could also have seen Earl Hines and Jack Teagarden, two legendary figures who helped transform the way we think about the piano and the trombone in jazz.

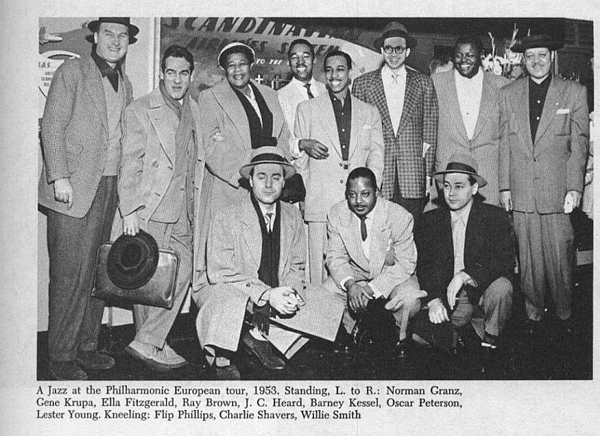

During the magical period I am concerned with Jazz at the Philharmonic Concerts helped introduce British audiences that had been starved of American performers since the mid-1930s to a host of stars (1). Let me just give you a flavour of what I mean. At one of the first Jazz at the Phil. Concerts I attended the four saxophonists who appeared were Coleman Hawkins, Don Byas, Benny Carter and Cannonball Adderley and three of the brass players were Roy Eldridge, Dizzy Gillespie and J. J. Johnson. Ella Fitzgerald, Oscar Peterson, Ray Brown, Shelly Manne, Jimmy Giuffre and Stan Getz were just some of the stars I heard on other Jazz at the Phil. evenings.

And there were big bands. At the start of my golden period Stan Kenton toured with what many regard as the greatest band he ever assembled. Then came Count Basie with an orchestra that included Frank Foster, Frank Wess, Joe Newman and the man who underpinned and swung every beat of the band, guitarist Freddie Green. The great Duke Ellington Orchestra also toured, an orchestra that featured Clark Terry and Lawrence Brown and a saxophone section that included such immortals as Johnny Hodges, Harry Carney and Paul Gonsalves. We will never hear their likes again.

There were also some memorable smaller groups that I managed to see and enjoy. My personal favourite would be the Modern Jazz Quartet, which for all its pristine delicacy swung mightily, and then there was the Dave Brubeck Quartet, which, even if it rarely swung, featured the hauntingly distinctive Paul Desmond on alto. With the Erroll Garner Trio, the piano was very much in the foreground, the swing was prodigious and Garner’s trademark introductions perplexed not just his audiences, but bass player Eddie Calhoun as well. (Calhoun confided after a concert in Birmingham that even if he guessed what tune Garner was about to light upon, he might still have to find its key, for Garner might play the same tune in different keys on different nights.)

Miles Davis

Two quintets I saw during those wonderful few years obviously deserve a mention: there was The Miles Davis Quintet, with the unrelenting Sonny Stitt on alto, a performance that included some back-to-the-audience posturing, but since I was in the choir stalls, this meant that Miles turned to face me; and I heard a John Coltrane Quintet, where the leader shared front line duties with Eric Dolphy, and went to great lengths on ‘My Favourite Things’.

Amongst the local musicians I heard during my jazz nurturing, Alex Welsh, Wally Fawkes, Bruce Turner, Tubby Hayes, Diz Disley, Danny Moss and Roy Williams all left lasting impressions, but for me the most strikingly original of all those jazz musicians I thought of as home-grown was the Indian-born, Edinburgh-educated Sandy Brown . His LP ‘McJazz’ (2), recorded in 1957, blew the idea that a traditional jazz line-up could only play traditional jazz clean out of the water. That originals by band members were lesser fare than material by ‘proper’ composers is something else that ‘McJazz’ seriously holed. After all these years, ‘McJazz’ is still surely one of the finest jazz recordings by a British band.

Sandy Brown

So, was the nine or ten year span I have recollected truly golden or was it something lesser that just happened to glister? Well, for a start it needs to be stressed that the so-called veterans I have mentioned were not just famous names from the past; they were still playing with considerable vigour during the period I have in mind. Those who heard Armstrong and Ory as well as Bechet, Teagarden and Earl Hines in the 1950s were being treated to performances by musicians with much to offer. Then we have to take into account the spread of jazz history covered by the musicians I have named. Could it ever be bettered? Imagine in the space of just a few years being able to hear Armstrong, Eldridge, Gillespie and Miles Davis. There was the history of the jazz trumpet in four wonderful and, so some historians would have us believe, consecutive chapters. Or think of hearing Ory, Teagarden and J. J. Johnson, or Hodges, Benny Carter, Adderley and Paul Desmond or Hawkins, Byas, Getz and Coltrane. The then and the now of jazz instrumentalists, all in fine form and when they played, no one took any prisoners.

Within another decade or so some of these great voices would be silent, some would lose their power and flair and what had been my golden age would have lost some of its stars and some of its brilliance.

Was there ever a better time to be a jazz fan than the period I have outlined? Or has nostalgia really got in the way of my better judgement? I doubt it.

Peter Gardner

January, 2018

Acknowledgements

I am most grateful for the help of Steve Marshall from Marshall McGurk, Maryport, Cumbria, and Dawkes’ woodwind specialist, Sam Gregory.

Endnotes

(1) See my ‘’The Ban’ – When Duke & Hawk were job-snatching aliens’, Dawkes Music Newsletter, 30th April, 2016.

(2) All of the tracks from the original ‘McJazz’ LP plus tracks from several 1956 to ’58 sessions featuring Sandy Brown can be found on the CD: Sandy Brown, ‘McJazz & Friends’, Lake LACD 58.