Artie Shaw – The Last, the Very Last, the Final Gramercies

8th December 2017Join jazz aficionado Peter Gardner as he discusses the excellent late recording work of clarinettist Artie Shaw…

It wasn’t until about twenty years ago that I realised that such marvellous recordings existed. I was in a large bookshop in the north of England and I had been told the bookshop also stocked some jazz CDs. As I recall, there weren’t too many jazz CDs there and most seemed to be by John Coltrane and Miles Davis. But somewhere near the end of the jazz shelves, perhaps between Rollins and Tatum, I came across a double CD whose attention-grabbing title had the words ‘…The Last Recordings Rare and Unreleased’.

A couple of weeks later I was in the same shop and in roughly the same place on its jazz shelves I came across another double CD whose title spoke of ‘…More Last Recordings : The Final Sessions’. On subsequent visits I failed to find ‘Even More Last Recordings’ or ‘Additions to the Final Sessions’. Still, without going out of my way and without my purchases being prompted by any kind of research, I had acquired thirty-seven tracks, nearly four hours worth of music, by the last of the small groups that Artie Shaw took into the recording studios, groups that carried the name of his earlier 1940’s ventures into small group jazz, The Gramercy Five, and those thirty-seven recordings were a revelation (1).

Artie Shaw

Shortly after Benny Goodman had been dubbed ‘The King of Swing’, the popular and the musical press in America crowned Artie Shaw ‘The King of the Clarinet’. The boy, once known as Avraham Ben-Yitzak Arshawsky, had become a tall, dark and handsome bandleader, who sold millions of records, dated Hollywood’s most beautiful stars, disbanded and reassembled his orchestras with some regularity, ‘retired’ and returned, and frequently displayed annoyance at the trappings of celebrity. Artie Shaw was a wonderful clarinet player, but a difficult man to live with, as each of his eight wives would no doubt have testified.

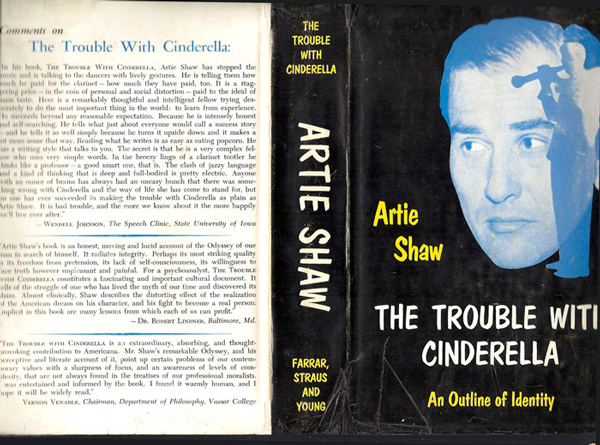

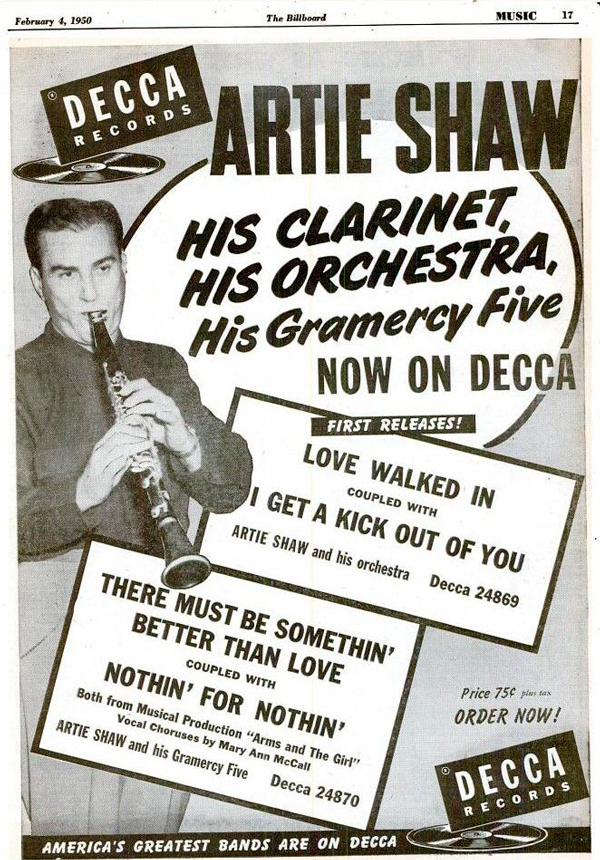

By the early 1950s, with the Swing Era and his great hits, such as ‘Begin the Beguine’, ‘Frenesi’ and ‘Stardust’, very much in the past, Artie Shaw was under contract to Decca Records and was producing such forgettable recordings as ‘I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles’, with an angelic choir, ‘It’s a Long Way to Tipperary’, ‘Show Me the Way to Go Home’, on which he sang, and ‘Jingle Bells’. Maybe Artie, who was usually driven to aim for perfection, was able to produce these lightweight efforts because his energies were directed elsewhere; he was pursuing his other great passion, writing. His much-awaited autobiography, The Trouble with Cinderella: An Outline of Identity, was finally published in May 1952. Artie’s next visit to Decca’s studios with a full-sized orchestra was probably on 2nd July, 1953, and on that occasion he did produce something of which he was justifiably proud. He improvised a cadenza at the end of ‘These Foolish Things’ which is truly astonishing (2). He would later say, “I did certain things in that cadenza that I thought – ‘That’s good; that’s as close to perfection as you’re going to get.’” Yet, there is something else to notice in the four recordings made that day; Shaw’s sound had become less assertive. Speaking of their differences as clarinet players, Benny Goodman maintained that Shaw’s “sound was more open. It carried a lot farther (than mine)”, but by 1953 Shaw’s bold, full-toned, bravura style of the Swing Era had softened and mellowed into something that wouldn’t carry very far. It was a sound for attentive listeners, not the dance hall.

Artie Shaw Biography – ‘The Trouble with Cinderella’

Not long after his Decca recording session Shaw had an offer to take a small group into what many have described as the “intimate” setting of New York’s Embers Club and he put together a sextet of carefully chosen musicians, several with experience of the new developments in jazz. These included African Americans Hank Jones on piano and Tommy Potter on bass along with drummer Denzil Best, whose parents were Barbadians. The guitarist Artie chose was Tal Farlow and on vibraphone he hired Joe Roland, who had recently been playing with George Shearing. Like several earlier Gramercy Fives, this new one, with Shaw on clarinet, would be a sextet.

Some measure of how determined Artie could be in his pursuit of perfection is revealed in Tom Nolan’s account of the new Gramercy Five preparing for its two-month Embers engagement. “Shaw held paid rehearsals…for an extraordinary six weeks – almost as long as the scheduled eight-week gig” and then “secured a late-September one-week shakedown gig at Boston’s Hi-Hat Club prior to the Embers October opening.” But the reviews for the Embers performances showed that such careful preparation wasn’t wasted; the arrangements and all the soloists, not just Artie, were praised and attention was drawn to Artie’s “warm, cozy style”, a style that, though less exciting than in former times, had “the composure of a true artist” as he led a group that was “gentle” and “strictly for listening”. For some reason Artie wasn’t happy with Denzil Best and he brought in Irv Kluger, a drummer who had played with Shaw in the 1940s and in 1950, as a replacement.

Feb 4th 1950 – Gramercy Five Advertisement

Fearing that the music of Shaw’s new group was too refined for the record-buying public, no major record company offered to take the sextet into a recording studio. Undaunted, Artie decided to finance a series of recordings himself. He began recording his new sextet in New York in December 1953 and again in the early months of 1954 also in New York. The tunes recorded included some familiar Gramercy Five numbers from the 1940s, such as ‘Summit Ridge Drive’, ‘When the Quail Come back to San Quentin’, ‘The Grabtown Grapple’ and ‘The Sad Sack’, as well as reworkings of some of Shaw’s big band successes, ‘Begin the Beguine’, ‘ Star Dust’ and ‘Frenesi’. Keen to avail himself of the greater time that the long playing record offered, these new versions of the earlier familiar tunes were often much longer that the original 78 r.p.m. recordings. The new versions of ‘The Sad Sack’ and ‘The Grabtown Grapple’ lasted over six and ten minutes respectively, while Shaw’s 1954 treatment of ‘Star Dust’ lasts nearly six. And while there are glimpses of the earlier renditions, this does not prevent the new sextet’s versions sounding like gentle and mature originals. As for Shaw’s sound, in his notes for several of these recordings, Dan Morgenstern wrote, “Glorious as it had been in 1938, it is even lovelier here.”

After its initial engagement, the new Gramercy Five toured for a while before returning for another successful spell at the Embers. Then, in April 1954, a smaller version of the group, now an actual quintet, was booked into the Casbar Lounge in Las Vegas’ Sahara Hotel. The quintet no longer had a vibes player and Joe Puma was the new guitarist. After the Casbar engagement the group played in San Francisco and in June Shaw financed more private recordings, this time in Hollywood. Rodgers and Hart’s ‘My Funny Valentine’ and Kern and Harbach’s ‘Yesterdays’ are two delicious ballads from these Hollywood sessions.

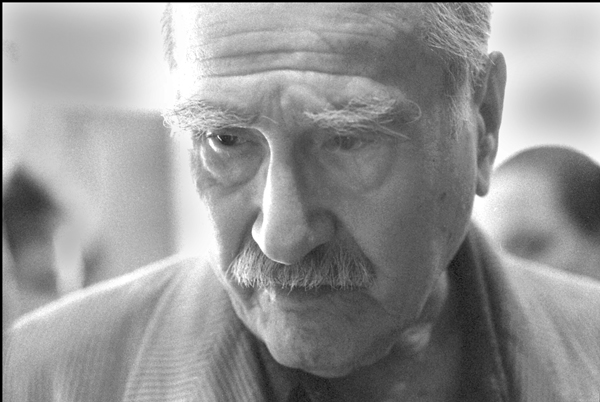

Unfortunately, these were to be the group’s last recordings. Within a short space of time, Artie Shaw had stopped playing and had moved to Spain, where he devoted his time to writing a novel, designing a castle, fishing and courting the woman who would become his eighth wife, the actress and novelist Evelyn Keyes. Artie Shaw lived until 2004 when he was ninety-four, but in the decades after the 50s, though there would be a few occasions when he conducted orchestras, he never again appeared as a clarinettist in public or in a recording studio. During their years in Spain together Evelyn Keyes could only recall one brief occasion when her husband played the clarinet. Even then “All he did was play some scales. Up and down. Over and over…It was the only time.”

So, The Gramercy Five recordings from 1953/54 are Shaw’s final recorded statements as a clarinettist. In 2012, when Jasmine issued a five CD collection described as ‘The Complete Commercially Released Recordings’ by The Gramercy Five, the collection contained forty-seven tracks from the 1953/54 period, including ten from the last sessions in Hollywood in June 1954 (3). With many tracks lasting over seven minutes, it is clear that Shaw’s final small group recordings constitute a substantial body of work.

Artie had chosen his sidemen for these groups based on his knowledge of their talents and abilities and, in the main, he had kept them together during rehearsals, engagements and recordings. Years later, when he reflected on their achievements, he had praise for them all, with pianist Hank Jones receiving a special and much deserved commendation. As for Shaw, he said he switched from his customary Selmer clarinet to a Buffet in order to get the sound he wanted with his final sextet and quintet (With a Buffet “I was able to get a more intimate, woody sound that blended with that small group.”). Artie also said that he used just enough air to keep the reed vibrating (“I was playing so softly that I was almost in a subtone mode – even in the upper register.”) and he played deliberately close to the microphone (“Sometimes you can hear the keys clicking.”). The result, Artie found, was “more intimacy and warmth – a lot more warmth”.

Shaw had progressed, both stylistically and harmonically, from the Swing Era, and critics have seen his final recordings as showing that he was still developing as a musician. They have also noted that within a few years of the final Gramercy Fives trying to produce what Artie described as “a sound like a chamber group”, the cooler sounds and the chamber jazz of small groups led by Gerry Mulligan, Chico Hamilton, Jimmy Giuffre and John Lewis would attract a huge following. So, the same critics have speculated, if Shaw had only stayed on the scene, then … But Artie was a restless man. He had a castle to build, fish to catch and novels to write. In any case, as he said of his final sessions, “That’s it. That’s all I have. That’s the best I can do.” Jazz authority and historian John White was a little more expansive about Shaw’s final recordings: “Every track contains its own delights and revelations, and it would be invidious of me to single out a particular performance. Suffice it to say that in the company of sympathetic and accomplished sidemen, these ‘last recordings’ are essential items in the Shaw discography. Like the best of small group swing/jazz, they offer inventiveness, intelligence, involvement, rhythm and (not least) rapture. Ironically, they also suggest that Shaw was perhaps at the height of his powers as an improviser on the eve of his (final) retirement.”

Artie Shaw in later life

In 2001, when Shaw was given the invidious task of making a selection of recordings from his entire career for the five CD boxed set ‘Self Portrait’, he chose several by his final Gramercy Fives (4). One of those, from March 1954, is a version of Henry Nemo’s song, ‘Don’t Take Your Love from Me’. The recording is a piece of magical understatement, or, as the critics would have it, a “feat of musical levitation” where there “is no imaginary way in which one bar, one phrase, could be bettered”. But there are many magical moments in Shaw’s ‘last recordings’. Do, please, try to find them and listen carefully. You, too, could be in raptures.

Peter Gardner – November, 2017

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to Steve Marshall, Marshall McGurk, Maryport, Cumbria, and to Sam Gregory, Dawkes’ woodwind specialist.

Endnotes

(1) The two double CD sets I have mentioned are: ‘Artie Shaw – The Last Recordings Rare and Unreleased’, Music Masters 01612-65071-2 (1992); and ‘Artie Shaw – More Last Recordings: The Final Sessions’ Music Masters 01612-65101-2 (1993). ‘The Last Recordings’ consists of tracks from both the New York and the Hollywood recording sessions. ‘More Last Recordings’ consists of tracks from the New York sessions and only one track recorded in Hollywood. Both compilations have excellent notes by Dan Morgenstern and Loren Schoenberg, and both compilations can still be found, though my research suggests that ‘More Last Recordings’ is becoming increasingly expensive. I would say the Jasmine collection (See (3) below) is the best buy in this area.

(2) ‘These Foolish Things’ from 2nd July, 1953, along with the three other tracks recorded at that session can be found on the double CD ‘Artie Shaw: These Foolish Things: The Decca Years’, Sepia 1314. This compilation also contains ‘I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles’, ‘It’s along Way to Tipperary’, ‘Show Me he Way to Go Home’ and ‘Jingle Bells’.

(3) Here are the details for Jasmine’s 5 CD collection: ‘Artie Shaw and His Gramercy 5, “Six Star Treats”, The Complete Commercially Released Recordings’, Jasmine JASBOX 20-5. This excellent and extensive collection includes recordings by Shaw’s earlier Gramercy Five groups and all the tracks from the two Music Masters compilations mentioned above. This Jasmine collection can still be bought at a reasonable price. It is strongly recommended.

(4) ‘Artie Shaw – Self Portrait’, Bluebird RCA 09026-63808-2 (2001). This is a 5 CD boxed set.

Some sources used

Evelyn Keyes, Scarlet O’Hara’s Younger Sister: My Life In and Out of Hollywood (W. H. Allen, London, 1978).

Notes from ‘Artie Shaw – The Last Recordings Rare and Unreleased’, Music Masters, 1992; notes from ‘Artie Shaw – More Last Recordings: The Final Sessions’, Music Masters, 1993; and notes from ‘Artie Shaw – Self Portrait’, Bluebird, 2001.

Tom Nolan, Three Chords for Beauty’s Sake (W. W. Norton, New York, 2010).

John White, Artie Shaw: Non-Stop Flight (The University of Hull Press, Hull, 1998).