Benny Carter: ‘The King’

11th October 2016…he is a king, man! You got Duke Ellington, Count Basie, and my man the Earl

of Hines, right? Well, Benny’s right up there with all them cats. Everybody

that knows who he is call him King! He is a King!

Louis Armstrong

Generations of jazz fans grew up in the firm belief that the three greatest alto saxophone players were Johnny Hodges, Benny Carter and Charlie Parker. Of this wondrous trio, only one could claim to be multi-talented; he was Benny Carter. His principal instruments were the alto sax and trumpet, which prompted someone with the pen-name of Snooty McSiegle to wax poetic:

Johnny Hodges

Sounds Gorgeous.

He knows how to jump it.

But Benny Carter is smarter.

He doubles on trumpet.

Benny Carter with Trumpet

Carter was also a very fine clarinettist and, in addition, he recorded on tenor and soprano saxophones, on trombone, piano and as a vocalist, and is reported as being able to play every dance band instrument. His recording career spanned over seven decades and his output was phenomenal; one chronological discography is over three hundred and seventy pages long. Some of his first arrangements were for the influential Fletcher Henderson Orchestra in the 1920s and in the decades that followed, including a spell in the 1930s when he wrote for the BBC’s Dance Orchestra, he proved himself to be an arranger that very few could ever hope to equal and arguably his writing for saxophones has never been bettered. He was also a respected bandleader, who helped further the careers of such modern thinking musicians as Miles Davis, J. J. Johnson and Max Roach, and he was composer, with standards and numerous film and television scores amongst his credits. His trailblazing work in Hollywood in the 50s and 60s and his work with musicians’ unions opened doors, once firmly shut, for Afro-American arrangers and players. Quincy Jones expressed his gratitude this way: “Benny opened the eyes of a lot of producers and studios, so that they could understand that you could go to blacks for other things outside blues and barbecue. He’s a total musician. He was the pioneer, he was the foundation. He made it possible for that doubt to be taken away.”

And Carter never seemed to slow down. Writing in 2001 his biographers observed: “Since turning eighty in 1987, he has written and performed six extended works; recorded some sixteen albums… composed dozens of new songs…toured the world many times, including ten trips to Japan and his first visits to Poland and Thailand…garnered seven Grammy nominations and (won) two Grammys…”(Berger, Berger and Patrick, p. 403). In fact, Carter received many prestigious music awards and numerous honorary degrees, he has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, he was honoured and feted by presidents and taught at Harvard, Princeton and Rutgers. On the occasion of his eighty-ninth birthday the Wall Street Journal carried an article with the headline: Benny Carter: 70 Years in Jazz (So Far). Oct. 7th is Benny Carter Day in Los Angeles, Oct. 8th is Benny Carter Day in New York City, in San Francisco it’s Dec. 5th…

Benny Carter with Alto Sax

Carter’s tone on alto was sweet with a slightly sultry edge, and his solos, invariably rich in decorative detours, were imbued with an elegance that no other alto player has ever approached, and they had structure and completeness; Carter’s improvised solos, though effortlessly spontaneous, could never be seen as works in progress. Little wonder that he was called “the Fred Astaire of the saxophone”. Gene Lees had this to say about Carter the altoist: “If you’re familiar with his playing, you can identify Benny Carter in about one bar. Nobody in the world phrases like him, no one inflects notes the way he does, no one has that urbane, gentle, aristocratic tone.”

Memorable Carter alto solos are to be found from all stages of his career, but one that I would like to draw particular attention to comes from a famous jam session that impresario Norman Granz organised in the summer of 1952. As luck would have it, Johnny Hodges, Charlie Parker and Benny Carter were all in Los Angeles at the same time and Granz arranged for the three alto stars to meet up in LA’s Radio Recorder studios with a wonderful rhythm section consisting of Oscar Peterson, Barney Kessel, Ray Brown and drummer, J. C. Heard. Tenor players, Ben Webster and Flip Phillips, and trumpeter, Charlie Shavers, were also added to the all-star line up. On the tantalizingly slow and delightfully simple ‘Funky Blues’, Hodges takes the first solo and produces, as he frequently did on the blues, a solo of moving simplicity that never sounds in the least contrived. Parker follows with two choruses that mix an earthiness with some of bop’s edginess and harmonic innovations. Next we have Carter. For someone who came to the fore in the swing era, we would not expect a display of bebop’s angularity, and in Carter’s two-chorus solo we certainly don’t find the rhythmic sparks that first made Gillespie, Parker and their coterie sound so eccentric in many people’s ears. Yet, from a harmonic perspective, Carter’s solo shows he has command what bebop brought to the jazz table. But, because of its effortless construction, his solo’s harmonic extravagance hardly draws attention to itself. The same might be said of Carter’s technical mastery. As Cannonball Adderley observed, “Benny could, and can, play as many notes as anyone, but he makes it look so easy. Some of the younger players make it look hard and therefore spectacular.”

Tracks from the Granz jam session appeared on the CD ‘Charlie Parker, Jam Session’, Verve 833 564-2, which includes ‘Funky Blues’. The tracks from the Verve CD also appear in ‘Charlie Parker: Legendary 1952 Jam Session’, Definitive Records, DRCD 11254.

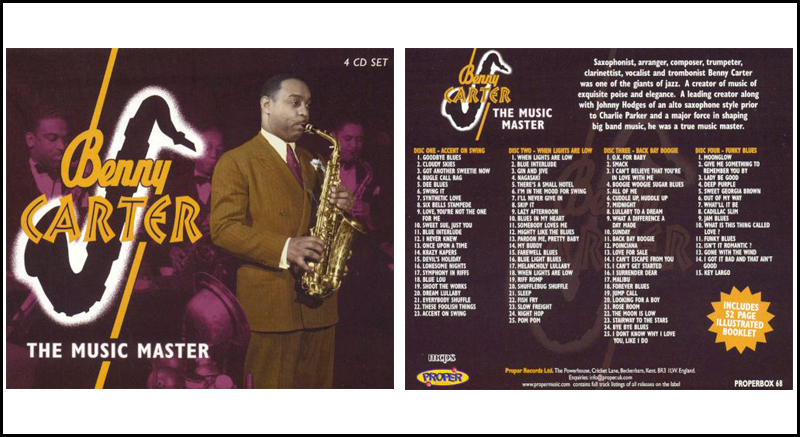

‘Benny Carter: The Music Master‘ 4CD Box Set – Proper Box 64

Those wanting to develop an appreciation of the first twenty years or so of Carter’s career will find the four CD set ‘Benny Carter: The Music Master’, Proper Box 64, with detailed notes by Joop Visser, well worth searching for. This particular collection begins with Carter’s recordings with The Chocolate Dandies, in New York in 1930, has several recordings made by Carter in England, Holland and France during the 30s and ends with four tracks Carter recorded with the Oscar Peterson trio plus drummer, Buddy Rich, in 1952. Another useful collection is Quadromania’s four CD set, ‘Benny Carter: Royal Garden Blues’, Membran 222416-444, which devotes most of its first two CDs to Carter’s 1930s recordings in Europe, and the whole of its fourth CD is made up of Carter’s recordings in the 1950s with Oscar Peterson groups. Unfortunately neither the Proper nor the Quadromania collection have four wonderful tracks recorded in Paris in April, 1937, by Coleman Hawkins and His All Star Jam Band, a group that, in addition to Hawkins, featured Benny Carter on alto, trumpet and as arranger, and guitarist, Django Reinhardt. These particular tracks are most likely to be found on Reinhardt compilations, such as ‘Djangology: Django Reinhardt, the gypsy genius’, Giants of Jazz CD 53002. Another attractive Carter compilation, though you may need to shop around to avoid some sellers’ high prices, is Membran’s double CD ‘Jazz Ballads, 14, Benny Carter’ 222544-311. This starts with the Benny Carter Orchestra in New York in 1940 and includes six tracks from the 1954 session where Carter recorded with the legendary pianist, Art Tatum.

Benny Carter has also appeared in some more recent releases. The Avid double CD, ‘Benny Carter: Four Classic Albums Plus’, AMSC 1048 has many examples of Carter’s effortless soloing and three of the chosen albums, ‘Jazz Giant’, ‘Swingin’ in the ‘20s’ and ‘Sax ala Carter’ allow us to hear Benny in relaxed small-group settings in the company of such illustrious musicians as Ben Webster, Earl Hines and Jimmy Rowles. Talking of illustrious companions, it would be seriously remiss of me if I did not mention the CD, ‘Benny Carter, Further Definitions’, Impulse 12292, part of which consists of tracks from a 1961 recording session that featured a similar line-up to the 1937 All Star Jam Band recordings and involves some examples of Carter’s wonderful writing for saxophones and some eloquent playing from the likes of Coleman Hawkins, Charlie Rouse, Phil Woods and, of course, Carter himself.

Benny Carter in later years

In an article written over thirty years ago, Earl Okin considered Carter’s “status as jazz’s first great alto voice” and whether he was still one of the greats. Faced with the fact that Carter was no longer topping jazz polls, Okin argued that such polls tend to favour those who have “attempted to take jazz in new directions”, which was never Carter’s way. Carter’s versatility was also seen as a weakness; “The public …seem not to be able to believe that one man can do several things at the same high level”. But despite Carter never being a jazz “revolutionary” and despite his undoubted versatility, Okin pugnaciously concluded: “He is still the finest alto player in the world. Now does anyone want an argument?”

Irving Mills, when manager of Duke Ellington, is said to have given Benny Carter the title ‘King’ in the 1930s. No one familiar with Carter’s talents and achievements has ever doubted that such a title was warranted, though some of his many fans may have sought a more elevated accolade for their hero. After all, as one headline writer put it, Benny’s From Heaven.

Benny Carter died on 12th July, 2003, just a few weeks before his ninety-sixth birthday.

Peter Gardner

October, 2016.

Acknowledgement

I am grateful for the help of David Nathan, Jazz Archivist, National Jazz Archive, Loughton Library, Trapps Hill, Loughton, Essex, IG10 1HD.

Some sources used

Morroe Berger, Edward Berger & James Patrick, Benny Carter: A Life in American Music, Vols. I and II (Scarecrow Press, Lanham, Maryland, 2002).

Gene Lees, Waiting for Dizzy (Oxford University Press, New York, 1991).

Earl Okin ‘Benny Carter: the cat with nine lives’, The Wire, Issue 9, Nov., 1984.