Benny’s Tales

19th April 2017Join Jazz aficionado Peter Gardner as he explores the great Benny Goodman…

It has become part of jazz folklore that once upon a time in a Chicago slum, shortly after the end of the First World War, a desperately poor Jewish father, who had emigrated to America from Eastern Europe, decided that some of his children might benefit from learning to play musical instruments. On hearing that a nearby synagogue ran a band for boys, the father took three of his twelve children to meet the synagogue’s band master.

The three boys were duly matched by age and physique to musical instruments: the largest of the three, Harry, was provided with a tuba; the next was given a trumpet; the smallest, Benjamin David, who was about ten years old, was given a clarinet. Within the space of just a few years, Benjamin, still in short pants, was astonishing the musicians who heard him with his tone, his technique and his ability to improvise chorus after chorus even on tunes thought of as having difficult changes. By the age of fourteen Benny Goodman was a professional musician playing in and around Chicago.

Another piece of jazz folklore is that in the summer of 1935, Benny Goodman began a tour that would take him and his band from New York to America’s West Coast. The tour turned out to be a disaster with the band playing to unresponsive, even hostile, dancers in ballroom after ballroom as it made its way to California, and there were times Benny thought of jacking the whole thing in. The problem was that the band had been broadcasting late at night from New York, playing hot driving music, spurred on by the flamboyant and crowd-pleasing drummer, Gene Krupa, and the same music was not going down well with those who wanted a mixture of quick steps, waltzes and the occasional polka.

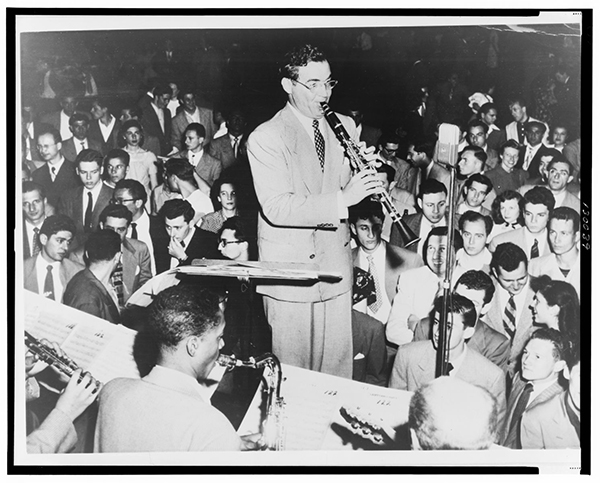

When the band opened up at California’s Palomar ballroom on 21st August, it began with the sweet music that had at least kept audiences peaceful in other venues, but after about an hour Benny decided that if he was going to go down, he would go down fighting. So, the band began playing its hot arrangements. The result was that the dancers surged round the bandstand, roared their approval of each new number and cheered every hot solo. The Swing Era was born right there and then in that ballroom on that night. Goodman’s stay at the Palomar was extended through September until October and the tour back across America was a resounding success as he and his band broke box office records wherever they appeared. The press would crown Goodman ‘The King of Swing’, king of an era that would last another eleven years or so.

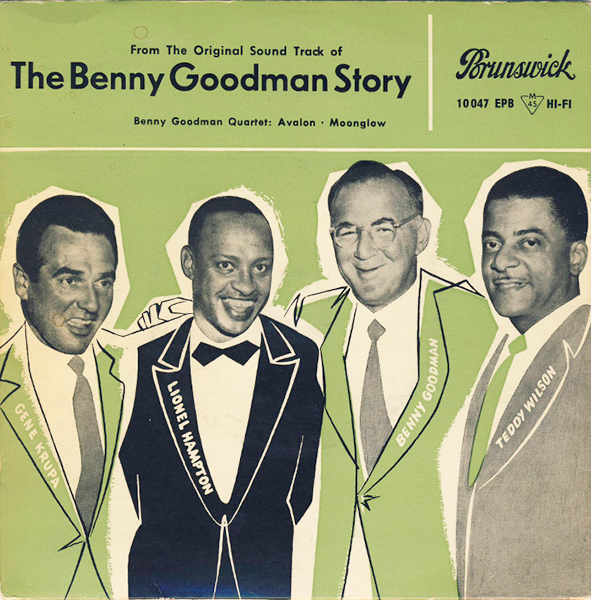

Our third tale involves someone who learnt to play the drums and, then, the xylophone in a band organised by the Chicago Defender newspaper mainly for its paperboys, but who would later move to Los Angeles. He would eventually become one of the jazz world’s great showmen. In the summer of 1936, when Goodman and his orchestra had returned in triumph to America’s West Coast, in addition to his star-studied orchestra, a Goodman evening would also feature the Benny Goodman Trio (1). The trio consisted of Goodman, clarinet, Krupa, drums, and on piano a young African American, who as a youngster had studied with Art Tatum and had honed his skills in the bands of Louis Armstrong and Benny Carter. He was Teddy Wilson. The trio had first recorded in July 1935 and, through its best selling records, public appearances and radio broadcasts, would become one of the most famous trios in the history of jazz. While on the West Coast someone told Goodman that a musician at Los Angeles’ Paradise Club would be worth checking out. Benny decided to pay the club a visit and took his clarinet along.

Some accounts say that the Paradise’s principal musical attraction was also a waiter, a bartender and, probably, a bottle-washer. But, whatever his other duties, Lionel Hampton had switched from the xylophone and had become a marvellous soloist on what at the time was something of a novelty instrument in the jazz world, the vibraphone. Goodman, who was thrilled by Hampton’s playing, spent the early hours of 20th August 1936 jamming with Hampton, returning later that evening with his trio and the four musicians jammed through the early hours of 21st August. Not content with that, the four met up in a Hollywood studio later in the morning to record a sumptuous version of ‘Moonglow’. The Benny Goodman Quartet was born. At Goodman’s famous Carnegie Hall appearance in January 1938 the Quartet’s version of ‘I Got Rhythm’, with Krupa and Hampton show-stoppingly prominent, brought the first half of the concert to a feverish close (2).

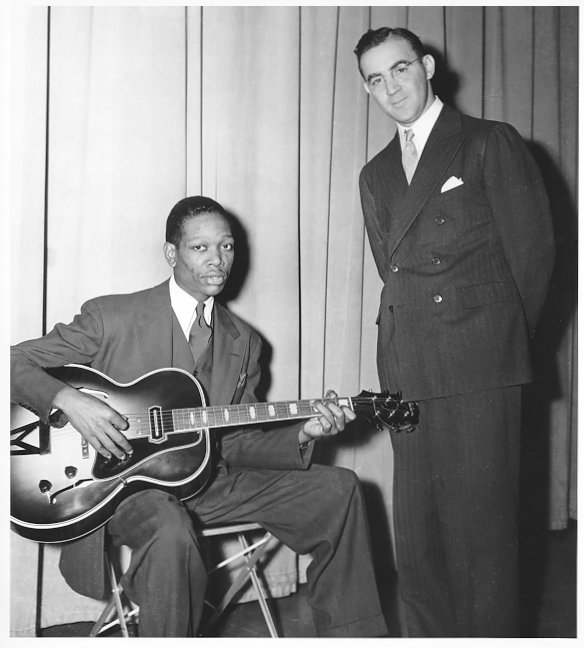

Our fourth piece of jazz folklore comes from 1939 and concerns a young man with extraordinary talent and vision, and a tragically short life. Pianist and arranger, Mary Lou Williams, had been singing the praises of a young man in Oklahoma City, Charlie Christian, who was doing wonderful things on the new-fangled electric guitar. John Hammond, a well-connected record producer, jazz columnist and talent-spotter, went to hear the young guitarist and brought him to Los Angeles to play with Goodman. Goodman initially showed no interest in the garishly dressed youngster, but Hammond, undaunted, took Christian to the Beverley Hills venue where Goodman was appearing. During an interval he led the guitarist onto the stage and made sure that Christian was plugged in and ready to play when Benny returned. On spotting the youthful interloper, Goodman called for ‘Rose Room’, a tune that had been composed over twenty years earlier, and which, being an old song, he hoped wouldn’t be one the young guitarist knew. However, Christian quickly joined in and jammed with Benny on ‘Rose Room’ for forty-five minutes.

For the next few short years Goodman’s small groups would usually feature America’s first master of the electric guitar. Before the end of 1939 Charlie Christian would have appeared with Goodman’s sextet at the Hollywood Bowl, on record, on several radio broadcasts and twice at Carnegie Hall, first in October for a concert for the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers and then in December for the second of John Hammond’s ‘From Spirituals to Swing’ concerts. Alas, while Christian’s career flourished his health deteriorated. He died of tuberculosis in March 1942, a few months short of his twenty-sixth birthday. Christian’s solo explorations and compositions were not just warmly received by Goodman; they were already paving the way for the music that Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie and Bud Powell would later perform with revolutionary zeal. Christian was welcomed at Minton’s Playhouse, where the boppers were cutting their teeth, not because he played with the most famous bandleader in the country, but because he was in tune with the new developments in jazz.

Charlie Christian with Benny

Of course, even if jazz folklore and historical truth have a nodding acquaintance, they have never been formally introduced. So, tales of how Benny got started, how he had his big breakthrough at the Palomar, how he met and jammed till dawn with the waiter, bartender and vibes player, Lionel Hampton, and how he tried to give the brush off to a brilliant guitarist in outlandish clothes, who would play an important role in the development of bebop, may all have been given more than a little polish over the years. But what needs no embellishment is that Goodman’s rival clarinettists in the entire history of jazz can be numbered on the fingers of one hand, and, as far as most critics are concerned, his only true rival was Artie Shaw, whose career was much shorter and whose social impact was much less that Benny’s. Goodman would appear in over twenty films, he would be the superstar and, in many people’s eyes, the instigator of what was known as ‘The Swing Era’ and he would be known internationally as ‘The King of Swing’.

On 18th January 1938 Benny Goodman and His Orchestra would give one of the first jazz concerts at New York’s famed home of classical music, Carnegie Hall, and he would eventually appear at Carnegie Hall on at least twenty-four occasions. Between 1931 and 1953 he would have one hundred and sixty-four hit records and his recordings of the Mozart Clarinet Concerto would be best sellers. Long after the Swing Era had become history he would carry on fronting big bands for special events and leading hot small groups with undiminished zeal. He would make international tours on behalf of the American State Department, Hollywood would make a film of his life, ‘The Benny Goodman Story’, he would be one of the very first white bandleaders to employ and appear in public with groups that included African American musicians – Teddy Wilson, Lionel Hampton and Charlie Christian might all be mentioned here – , and Goodman would carry on performing until shortly before his death in June 1986.

An astonishing musician and an astonishing career, with or without the folklore.

Peter Gardner

April, 2017.

Acknowledgement

I am most grateful for the help and patience of Steve Marshall.

Endnote

(1) The double CD ‘Benny Goodman, Trio and Quartet Showcase’, Primo PRMCD 6040, is a low priced and useful introduction to the Goodman trios and quartets in their heyday.

(2) Recordings from the famous Carnegie Hall Concert are available on various compilations. The competitively priced 10 CD boxed set, ‘Milestones of the King of Swing’, Documents, 12281, contains recordings from the Carnegie concert plus many other albums, including several tracks from ‘Benny Goodman in Moscow, 1962’. One of the tracks from the Moscow album, called ‘Medley’, which includes ‘Avalon’ and ‘Body and Soul’ amongst other tunes associated with Goodman, is an absolute tour de force. If you are a budding or even a well-bloomed clarinet player, try to listen to ‘Medley’.

Some Sources Used

Firestone, R. (1993) Swing, Swing, Swing: The Life and Times of Benny Goodman (Hodder and Stoughton, London).

Goodman, B. and Kolodin, I. (1961) The Kingdom of Swing (Frederick Ungar, New York).

Hammond, J. with Townsend, I. (1981) On Record (Penguin, Harmondsworth).

Hancock. J. (2008) Benny Goodman: The Famous 1938 Carnegie Hall Jazz Concert (Prancing Fish, Shrewsbury).