‘Big Ben’ by Peter Gardner

3rd November 2016In January 1967 Ben Webster was playing a short season at Ronnie Scott’s Cub in London. As often happened back then, star soloists who were playing at Ronnie Scott’s would play some out of town gigs. That was how, a few months earlier, I had heard Johnny Griffin in Coventry’s Leofric Hotel. Griffin, ‘The Little Giant’, ‘The Fastest Tenor in the West’, had left his audience enthralled and somewhat drained by his astonishing speed, unquenchable imagination and stamina.

Now I was on my way to hear a completely different kind of tenor player. On a cold and foggy January evening nearly fifty years ago, I was on my way to the Matrix Hotel in Coventry to hear the man that Ronnie Scott introduced as “A true jazz legend – one of the greatest tenor players jazz has ever known”. As I recall, Ben Webster, broad shouldered and portly, opened with some up medium tempo swingers, like ‘In a Mellow Tone’ and ‘What Am I Here For?’. There were no words spoken; he just counted in the tempo and played. Then it happened. Webster, with breath and vibrato, rather than a tone, eased himself into a familiar Irish melody, Stan Tracey felt for some gentle chords, and the room froze. Cigarettes remained unlit. People sat transfixed. At the bar drinkers stood silently with empty glasses, as if to order would ruin the moment. Ben Webster was playing ‘Danny Boy’. He had cast his spell and no one moved (1).

Ben Webster: jazz’s greatest ballad player?

Benny Green maintained that Webster’s tone in his later years “had grown so sumptuous that it seemed almost to possess a tactile quality, duping the listener into thinking he might reach out and run his fingers through its timbre”. My own view is that Webster’s sound itself stretched out, embraced and caressed you; soft, breathy and enveloping in the lower register, it had cello-like warmth in the higher registers that touched you like a delicate piece of fabric. And Webster’s statements, often little more than the bones of a melody, could be gentle to the point of being fragile. He had reached what Green sees as “that nirvana of the jazz soloist”, where, with “a tone so redolent of the jazz spirit, and his sense of time and rhythm …he could create authentic jazz just by playing the tune”.

Students of jazz, who are learning about chords, passing chords and substitutions and delving into devilish modes, will find the last statement truly remarkable. They may even find it paradoxical; for if improvisation lies at the heart of jazz, how can someone create authentic jazz by just playing a melody? The answer lies in tone, rhythm, time and, though Green omits this special ingredient, a good rhythm section, and Webster deservedly played with some of the finest.

Benjamin Francis Webster was born in Kansas City, Missouri, on 27th March, 1909. His parents split up before he was born and he was brought up by his great aunt, Agnes Johnson, to whom he would later show great affection and loyalty. In formal education Webster’s grades were impressive, but it was in music that he wanted to make his mark. Early lessons on the violin ended with a show of temper; he smashed his violin against a piano. He wanted to be a pianist. However, according to one of Webster’s biographers, Jeroen de Valk, his early experiences as a professional musician were far from encouraging; by 1927 the young pianist was working in a poorly paid band, touring “shabby dance halls in a dilapidated bus”, often eating chickens stolen from local farms and cooked over open fires by the roadside.

Surprisingly for someone who would become one of the great saxophone stylists, it was 1929 before Webster started to take an interest in the instrument. About this time he began travelling with Billy Young’s band, where he was given lessons on the alto, often by Billy’s son, Lester, who would also become one of the foremost tenor voices. Within a few months, Webster was on the road with another band, and he had switched to tenor. In the early 1930s he began to appear on recordings, but the results were not promising. Jazz authority, Gunther Schuller had this to say about Webster’s early efforts: “it is hard to realize – let alone believe – that one of the greatest balladeers in jazz (some would argue, myself included, the greatest) should have started as a buzz-toned, frantic, downright comical, slap-tongue saxophonist.”

From L to R: Duke Ellington, Ben Webster, Jimmy Hamilton

But Webster persevered and, it seems, listened to Coleman Hawkins’ recordings until “One day a guy (probably pianist Clyde Hart) said to me, “Well, Ben, you finally did it…You sound just like the Hawk now.” I packed up the record player and took it to Kansas City for my folks. From then on, I developed on my own.” Possibly because of tales like this, the “conventional theory”, as Gene Lees calls it, is that Webster “came out of Coleman Hawkins”. Yet, as Lees insists, Webster’s “big sound and slurs and push and bluff determination” meant that musically and otherwise Ben “was another thing entirely”. The Webster, who developed on his own, and who played with the Teddy Wilson orchestra in the late 1930s and later, and memorably, with Duke Ellington, had a directness and a physicality that set him apart from Hawkins. Webster got to the point with relish, never more so than in his famous solo on ‘Cotton Tail’ with the Ellington orchestra in May, 1940. The romantic Webster also flourished with Ellington. His second chorus solo on ‘All Too Soon’ from July, 1940, where we can delight in the rich warmth of his upper register, is a gem of ballad playing (2).

Webster left Ellington in 1943, though he would return for spells thereafter, and he began to appear in small groups in the clubs that helped New York’s 52nd Street become known as ‘Swing Street’ and ‘The Street That Never Sleeps’, where he would rub shoulders with the likes of Dizzy Gillespie, Billie Holiday, Art Tatum, Roy Eldridge, Charlie Parker…

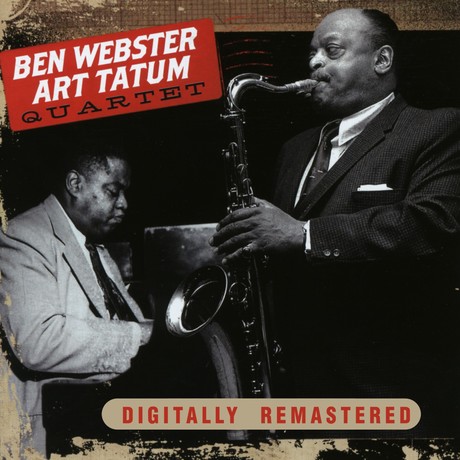

In the 1950s Webster moved to America’s west coast. There, often under the stewardship of impresario, Norman Granz, he featured in some memorable recordings, including one of the final albums made by the pianist Count Basie called “the eighth wonder of the world”, Art Tatum. If nature abhors a vacuum, Tatum seemed to abhor silence or space, filling any semblance of a rest with cascading runs or rich new chords the tune’s composer never dreamt of. Just as Tatum was busy, Webster was laid back. But their partnership in September 1956 worked and on such well-worn standards as ‘Where or When’ and ‘All the Things You Are’ the contrast of wizardry from the pianist and mellow melodic richness from the tenor player produces a musical treat. Alas, a little less than two months after recording with Webster, Art Tatum died at his home in Los Angeles. He was only forty-seven years old.

Granz also favoured teaming baritone player, Gerry Mulligan, with different saxophonists. As a result, Mulligan made memorable albums with Johnny Hodges, with Paul Desmond, and, in late 1959, with Ben Webster. The original LP ‘Gerry Mulligan Meets Ben Webster’ has since appeared with extra tracks on CD and with even more extra tracks as a double CD, ‘The Complete Gerry Mulligan Meets Ben Webster Sessions’. All versions, I would contend, live up to Nat Hentoff’s prediction in the original LP’s liner notes that the Mulligan-Webster session “will be listened to as long as one cares about jazz’ (3).

In 1964 Webster was offered his first engagement at Ronnie Scott’s and he never went back to America. Instead, he toured Europe, made several trips back to England, and in 1966 he became a tenant in a house in Amsterdam owned by Mrs. Hartlooper, a widow in her seventies. She mothered him as if he were her long lost son, though after a few years, Webster’s heavy drinking and long phone calls into the early morning to America became too much even for his adopted mother, and Ben moved to Copenhagen. He continued to tour and record, but in early September 1973 after a concert in Leiden, Holland, he suffered a stroke. Ben Webster died a few days later, on 20th September, in Lucas Hospital, Amsterdam.

Although at the time of his death Webster had a Selmer Mark VI tenor saxophone, he also had another tenor sax, his favourite instrument, which he called ‘Ol’ Bessie’ or ‘Ol’ Betsy’. This was a Balanced Action Selmer he had bought second-hand in the late 1930s and which he used for most of his life. While in Lucas Hospital, Webster had requested that, after he had gone, no one should play his favourite tenor. His Selmer Mark VI eventually went to Dexter Gordon, himself a legendary jazz star. In 1979, unplayed since Webster’s death, Ol’ Bessie was placed in the jazz museum in the Institute of Jazz Studies at Rutgers University, New Jersey, next to the Conn on which Lester Young, Webster’s early teacher, had initiated a new style of tenor playing during his time with Count Basie and on which Lester had accompanied Billie Holiday on many of her finest recordings.

As for other memorials, in 1972 a group of jazz writers and publishers proposed that 52nd Street should have a special pavement, like Hollywood Boulevard, that would have what author Arnold Shaw described as “medallions with the names of the great performers who made it the Jazz Mecca of the world”. ‘Swing Street’ would then have remembered Webster alongside Hawkins, Tatum, Charlie Parker, Billie Holiday and many others. Alas, the scheme was not pursued.

In Europe, albeit a few years after his death, Webster was accorded a memorial. Jeroen de Valk describes it in these terms: “In Holland, it took years before Ben Webster was awarded a lasting monument. In the eighties, however, a street was named after him in the neighbourhood of Zevenkamp in Rotterdam. The Ben Websterstraat is a short, angular street, with the appropriate cross streets of Fats Wallerstraat and Art Tatumstraat. The Coleman Hawkinspad and Duke Ellingtonstraat are a short distance away. Webster would have been delighted with this token of appreciation.”

Ben Webster deserves to be remembered in such elevated company.

Peter Gardner

November, 2016

Acknowledgements

This is my seventh piece for Dawkes’ Newsletter and I haven’t yet thanked the person who first invited me to write for Dawkes, who edits what I produce and finds suitable photos. He is one of Dawkes’ woodwind specialists and someone who has helped me greatly, Sam Gregory. I must also thank Steve Marshall for his patience and knowledge.

Endnotes

(1) The CD ‘Ben Webster – Stan Tracey, Soho Nights’, Vol. 1, Resteamed , RSJ 106, was recorded in Scott’s Club about one year after the evening I refer to and it features Webster accompanied by Stan Tracey playing ‘Danny Boy’/’Londonderry Air’.

(2 Both ‘Cotton Tail’ and ‘All Too Soon’ can be found on the strongly recommended double CD ‘Duke Ellington, Highlights of the Great 1940-1942 Band’, Avid AMSC 1143.

(3)There are other albums from the 1950s and early 60s that could be strongly recommended, several of which are available at present on low priced compilations, such as: ‘Ben Webster: Three Classic Albums Plus’, Avid Jazz, AMSC 1038, which contains the excellent album ‘Soulville’; ‘Ben Webster, Seven Classic Albums’, Real Gone Jazz, RGJCD 343, which contains ‘Soulville’ and the wonderful ‘Ben Webster Meets Oscar Peterson’; and ‘Ben Webster, The Complete Recordings, 1959-1962’, Enlightenment, EN4CD 9066, which has ‘Ben Webster Meets Oscar Peterson’. The last two compilations also have the tracks from the LP ‘Gerry Mulligan Meets Ben Webster’.

Some Sources Used

Jeroen de Valk, Ben Webster: His Life and Music (Berkeley Hills Books, California, 2001).

Benny Green, Notes for ‘Art Tatum: The Complete Pablo Group Masterpieces’, Pablo, 6PACD-4401-2.

Nat Hentoff, Liner Notes for LP ‘Gerry Mulligan Meets Ben Webster’ reprinted in Notes for ‘Gerry Mulligan Meets Ben Webster’, Verve 841 661-2.

Gene Lees, Waiting for Dizzy (Oxford University Press, New York, 1991).

Arnold Shaw, 52nd Street: The Street of Jazz (Da Capo, New York, 1977).

Gunther Schuller, The Swing Era: The Development of Jazz, 1930-1945 (Oxford University Press, New York, 1989).