“Faz” by Peter Gardner

9th March 2018The number of great clarinet players who were born or learned to play in New Orleans when jazz was in its infancy is quite amazing. Johnny Dodds, Edmond Hall, Albert Nicholas, Omer Simeon, Leon Roppolo, Jimmy Noone, Barney Bigard, Sidney Bechet and Irving Henry Prestopnik are just some that come to mind. If the last of these is not too familiar, maybe you know him under the Mediterranean name for ‘beans’, possibly acquired as a term of commendation, or because in his early days he only played from music in a prim and proper or ‘fah-so-lah’ kind of way. Still, whatever its etymology, ‘Fazola’ replaced the east European name of his father, ‘Henry’ was dropped and for most of his adult life he was known as Irving Fazola or ‘Faz’.

Born in New Orleans in December 1912, Fazola’s first music lessons were on the piano, but he soon switched his attention to the saxophone and then to the Albert system clarinet. For a while he dabbled with the Boehm system, though he soon went back to the Albert system and he would play Albert clarinets for the rest of his life, frequently doubling on alto saxophone and occasionally trebling on baritone. By the time he was in his late teens he had developed what John Chilton calls “three dominant interests that went with his passion for music, they were eating (his greed was so indiscriminate that he became known to all his pals as ‘The Goat’), drinking (at that age…Faz’s favourite tipple was gin, with beer chasers) and finding girls.” From his teenage years Faz had “an energetic interest in female company that never dwindled”. Those who knew Fazola well have also stressed that he could be fiery-tempered and aggressive and that his speech was littered with oaths and curses.

Fortunately art doesn’t have to reflect life and by the time Fazola was in his twenties his clarinet playing was a thing of beauty. He had a soft, full, round, liquid sound in all registers, his initial difficulties with improvising were a thing of the past and he had become an inventive and melodic soloist, and he swung effortlessly. Fazola’s early hero had been the famous clarinettist with the New Orleans Rhythm Kings, Leon Roppolo, but the style that Faz developed was much less assertive than Roppolo’s and Fazola’s tone was never strident. And, above all, it was his tone that marked Faz out as special. ‘Opulent’ and ‘creamy’ are just two of the adjectives that have been used to describe it. As for similarities, the sound that Barney Bigard produced in the 30s and the well-rounded tone of Jimmy Noone come close, though they lacked the richness, the opulence, Fazola could muster.

Not surprisingly Fazola attracted attention from famous bandleaders who were keen to add a star soloist to their reed sections, but for a few years Faz declined their lucrative offers; he was more than content playing, eating and drinking excessively and chasing women in his native city.

Eventually bandleader Ben Pollack lured Faz away from New Orleans. Ben Pollack was a drummer and the bands he led in the 1920s and early 30s included several musicians who would become major stars in the Swing Era: Benny Goodman, Glenn Miller, Jack Teagarden and Harry James all served apprenticeships in Pollack’s orchestras. Once Fazola began to tour with Pollack and had started to make records (1), such as ‘Song of the Islands’ (1936) and ‘Jimtown Blues’ (1936), he came to national attention, though the pursuit of fame was never one of Faz’s vices; he had plenty of others to take up his time and add to his girth.

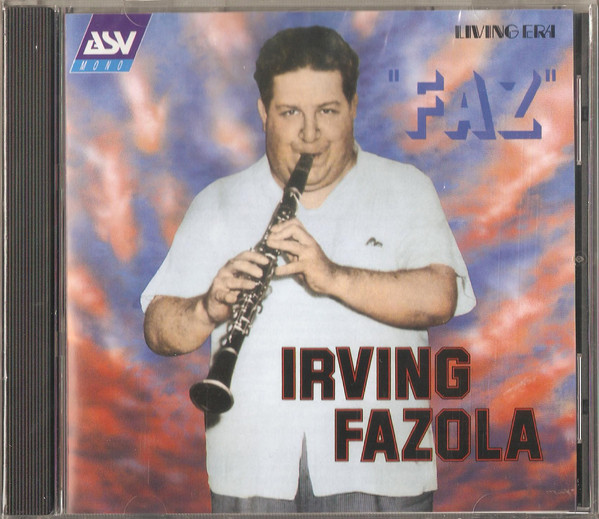

Living Era CD, ‘“Faz” Irving Fazola’ CD AJA 5279

A restless man when away from New Orleans, Faz’s stay with Ben Pollack soon ended After a brief spell with Glenn Miller and an even briefer one back with Pollack, Fazola made the most important move of his career, and, in a roundabout way, Ben Pollack would be linked to this new and important development as well. Let me explain. A couple of years before Faz left New Orleans, a band led by Pollack was touring and had reached California, but the band was not drawing the crowds or getting the promotion or the engagements its sidemen hoped for. Maybe the fault lay with the leader; all Pollack seemed interested in was furthering the career of the love of his life, the band’s girl singer, Doris Robbins. Unhappy at the way things were going, many of Pollack’s musicians decided to abandon their leader, to move to New York and to regroup. However, when ‘Pollack’s orphans’ got together in New York, they lacked a front man, someone to call the tunes, someone audiences would warm to, someone to hold a baton, even if a sideman was actually counting the band in. After a while, the orphans found a person who fitted the bill. He was tall, good-looking, had the right kind of personality and sang passably. He was Bob, the younger brother of Bing Crosby. So, ‘Pollack’s orphans’ acquired a front man and a name. They became the Bob Crosby Orchestra. In March 1938 Fazola joined Crosby and the period that Faz spent with the Bob Crosby Orchestra and its popular small group, the Bob Cats, would turn out to be the most productive of the clarinettist’s short career.

On 10th March, 1938, Fazola recorded Kokomo Arnold’s ‘Milk Cow Blues’ (2) with the Bob Crosby Orchestra, taking a two-chorus majestic and effortless solo before guitarist Nappy Lamare begins his tongue-in-cheek vocal. Playing behind Lamare’s vocal and later exchanging riffs with the trumpet section, we have what I take to be a wonderful clarinet trio of Fazola, Matty Matlock and Eddie Miller. Few bands have ever been so blessed with such a trio of clarinettists. Faz seems to be fitting into his new musical surroundings beautifully. A few days later Fazola recorded ‘March of the Bob Cats’ with the famous eight-piece small group drawn from the Crosby orchestra. As a tune, the ‘March’ is heavily indebted to ‘Maryland, My Maryland’ and Fazola’s two-chorus solo is a model of coherence and precision, perhaps reflecting his own experience of New Orleans marches. When he joins in the final choruses, Faz’s high note playing demonstrates that clarinettists needn’t be fussy to be effective ensemble players. But Fazola’s most famous recording with Crosby wouldn’t be made for another seven months.

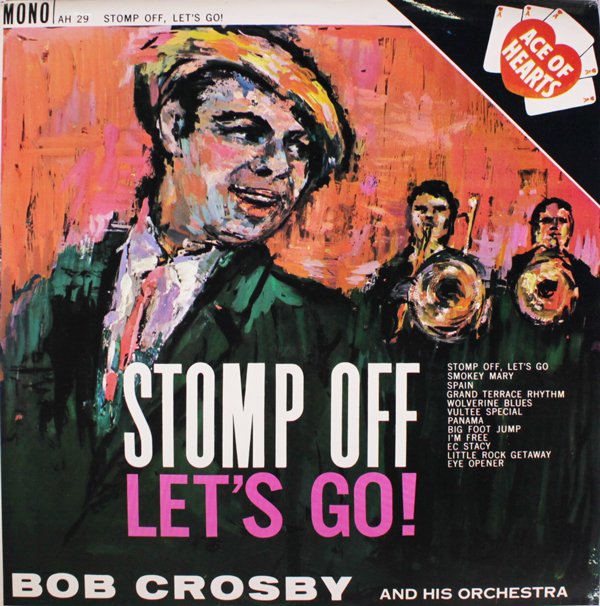

‘Stomp Off, Let’s Go! The Bob Crosby Orchestra and the Bob Cats’

In October 1938 the Crosby orchestra recorded a tune by its bass player, Bob Haggart, that would be forever associated with Fazola. I don’t know whether ‘My Inspiration’ was written with Faz in mind, but the tune’s opening melody and sentiment fit him like the best of bespoke tailoring. On ‘My Inspiration’ Fazola is the only soloist and he begins by playing the first theme with a delicacy that is ideally suited to Haggart’s haunting melody. When the tempo quickens, he solos with relaxation and certainty while the orchestra swings lustily behind him. Later clarinettists, like Bob Wilber, Kenny Davern and England’s Alan Barnes, would play ‘My Inspiration’ as a tribute to Fazola. During 1939 and at the start of 1940 Faz continued to make memorable recordings with Crosby’s big and small bands.

Among the various singers who appeared with the Crosby band, one of the youngest was Katherine Laverne Starks, who changed her name to Kay Starr and eventually became one of the pop world’s most successful vocalists. She toured with Bob Crosby when she was seventeen, with her mother as chaperone, and, apart from singing, the young Kay Starr had another important duty to perform. She protected Faz’s jug and prevented other sidemen from getting their hands on it. “He always called me little sister and gave me his jug to hold when he soloed because he trusted me and knew that I didn’t drink.”

But drinking on the bandstand was part of Fazola’s routine and may have contributed to what has been called ‘The Fazola-Conniff tussle’. According to one account, during a live performance, a particular passage in an arrangement required a fast trill from Fazola. Having visited his jug several times that evening, Fazola’s fingers could only move slowly. The fast trill wasn’t even medium-paced, and some of the band, including a young trombonist, Ray Conniff, found this amusing, much to Fazola’s annoyance. Conniff, who would later find international fame as an arranger, was not one of Fazola’s favourite people to start with, and his amusement at the sloppy trill led to Fazola exchanging words with him on stage and exchanging punches with him off-stage. Few punches, if any, landed, but the incident prompted Fazola to quit the Crosby band. As John Chilton has pointed out, Fazola “had never stayed for more than two years with any band” and “it is probable that (he)…would soon have left the band anyway”. So, perhaps the “tussle” was just the excuse that Fazola needed. Fazola left Crosby at the start of June 1940.

After playing for a while in New Orleans Fazola made a move that still seems surprising. He joined the Claude Thornhill orchestra. To-day Thornhill is remembered for harmonically progressive arrangements and swing versions of classical pieces. (Canadian Gil Evans, who rose to prominence in the 1950s through his arrangements for Miles Davis arranged for Thornhill in the 1940s.) Apparently Thornhill was delighted to recruit Fazola, who added a rich voice to the reed section and contributed short but delicate dixieland solos to Brahms’ ‘Hungarian Dance No. 5’ (1941) and Schuman’s ‘Traumerei’ (1941) amongst other well known classics (3).

Claude Thornhill and His Orchestra, ‘Snowfall’

At the start of 1942 Faz was on the move again. This time he joined Muggsy Spanier’s orchestra, this being a big band that Spanier hoped would be a great commercial success. Fazola also recorded with Muggsy’s small group, the Ragtimers, and had one “helluva fight” with one of Spanier’s arrangers. Brief stays with other bands ensued, but by the autumn of 1943, vastly overweight and suffering from high blood pressure, Fazola returned to his favourite city. In New Orleans he began to work on the radio, played in clubs, proved to be an inspiration for the young Pete Fountain and in the mid 1940s ‘Irving Fazola and His Dixielanders’, a seven-piece group, made several recordings for Keynote in New Orleans, including a delicious blues, ‘Mostly Faz’(1945). All of these recordings show that Fazola’s musical standards were undiminished.

By now his health was deteriorating. A man of medium height, some reports say that at times in his later years he weighed over twenty stones and was frequently out of breath. Yet, despite medical advice, he carried on eating and drinking to excess. He died in his sleep on 20th March, 1949. He was only thirty-six.

What I have always taken as one of the endearing qualities in Fazola’s clarinet playing, though some may see it as restrictive, is that he showed great respect for the instrument. He was never harsh or domineering or frantic or concerned with pushing boundaries. He was concerned with being mellow, melodic and warm, and, despite a tragically short career, the recorded evidence shows he succeeded wonderfully. Sadly appraisals of Fazola’s achievements often reveal the extent to which race imbues jazz criticism. ‘The greatest white New Orleans clarinettist’ and ‘One of the great white jazz clarinettists’ are the kinds of valuations I have in mind. Maybe we should just say he was one helluva clarinet player. After all, that’s what our ears tell us.

Peter Gardner

February, 2018

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Steve Marshall, Marshall McGurk, Maryport, Cumbria and Dawkes’ woodwind specialist who prepares Dawkes’ newsletters, Sam Gregory.

Endnotes

(1) Several of the recordings I mention, including ‘Song of the Islands’, ‘Jimtown Blues’, ‘My Inspiration’ and ‘Mostly Faz’, are on the Living Era CD, ‘“Faz” Irving Fazola’ CD AJA 5279.

(2) ‘Milk Cow Blues’ and ‘March of the Bob Cats’ are on the Living Era CD, ‘Stomp Off, Let’s Go! The Bob Crosby Orchestra and the Bob Cats’, CD AJA 5097.

(3) ‘Hungarian Dance No. 5’ and ‘Traumerei’ are on the Living Era CD, ‘Claude Thornhill and His Orchestra, ‘Snowfall’’, CD AJA 5542.

Some sources used

Vic Bellerby, Notes for ASV’s ‘Stomp Off , Let’s Go!’, Bob Crosby Orchestra and the Bob Cats, 1992 (AJA 5097) and ASV’s ‘Faz’, Irving Fazola, 1998 (AJA 5279)..

John Chilton. Stomp Off, Let’s Go! The Story of Bob Crosby’s Bob Cats and Big Band (Jazz Book Service, London, 1983).

George T. Simon, The Big Bands (Collier Macmillan, New York, 1974).

John R. Tumpak, When Swing Was the Thing (Marquette University Press, Milwaukee, 2009).