Fletcher Henderson

15th February 2020

“If Benny was the “King”, what then was Fletcher?”

– Gunther Schuller

“Goodman…opened the whole wide world of jazz to hundreds of thousands

who had never heard of Benny Carter or Fletcher Henderson.”

– Tom Scanlan

Henderson “made great recordings of his own compositions, which sold a

minimal number, only to have the same tunes and arrangements cut by Benny

Goodman with astronomical sales. No question about it; he was frustrated.”

– John Hammond

He appears in photographs taken during his heyday as a pale-skinned African American, with well-greased hair, perfectly combed, and a small well-trimmed moustache. Standing six-foot tall he looks a picture of respectability, which is what one might expect given that his father, Professor Henderson, was a high school principal and his mother, Ozie Lena, was a music teacher. Fletcher, the eldest of the Henderson’s three children, was born in Cuthbert, Georgia, in December 1897. He studied Chemistry at Atlanta University, where he also excelled at baseball and as a pianist, and he graduated in June 1920. At Atlanta he also acquired the nickname ‘Smack’, which, back then, had nothing to do with heroin. Fletcher may have acquired the name from the sound he made when kissing or the sound he made at the back of his mouth when sleeping or because it rhymed with his roommate’s nickname of ‘Mac’. Whatever the reason, the nickname had staying power; even in the 1950s Fletcher would be referred to as Smack.

New York and a Gathering of Stars

Fletcher arrived in New York at the start of the twenties. Perhaps he was going to undertake a postgraduate course in Chemistry. Maybe he started to work in a firm’s chemical laboratory. What we do know is that Fletcher roomed with a pianist who worked in a riverboat orchestra and, when his roommate was ill, Fletcher subbed for him. Soon more and more work came Henderson’s way. This was a time when America, or at least its record companies, discovered the blues, many sung by artistes called ‘Smith’, and not just Bessie. And singers needed accompanists. Some also wanted small orchestras.

Henderson obliged on both counts. Revella Hughes recorded with Henderson on piano and Lulu Whidby had the benefit of Henderson’s Novelty Orchestra, while more famous singers, like Ethel Waters and Alberta Hunter, also recorded with groups that featured Henderson and bore his name. Extensive touring with Ethel Waters and her Black Swan Troubadours, including engagements in New Orleans, and more recordings for Black Swan Records and other labels with the likes of Bessie Smith, Trixie Smith, Clara Smith and Ethel Waters meant that by the Spring of 1923 the once aspiring chemist had become an established figure among African Americans in New York’s recording studios.

The musicians that Henderson took on record dates to accompany singers or to record on their own, usually as ‘Fletcher Henderson and his Orchestra’, were starting to grow in importance. A man who played several reed instruments, Don Redman, became a regular member of Henderson’s recording groups in the early twenties and a principal arranger. Banjoist, Charlie Dixon, also made frequent appearances with Henderson as did a young tenor saxophonist, who had earlier been a member of Mamie Smith’s Jazz Hounds, Coleman Hawkins.

When these and other of Smack’s recording musicians appeared in public, Fletcher was picked to be their leader, not because he pushed himself forward, but because, as Don Redman recalled, “he was a college graduate and presented a nice appearance”. Henderson’s musicians began their first New York residence at the ‘Little Club’, better known as ‘Club Alabam’, near Broadway in January 1924. By July of ’24 Henderson’s group of musicians, now billed as The Fletcher Henderson Recording Orchestra, had secured an engagement at the prestigious Roseland Ballroom – it was one of the first African American bands to play at Roseland. Two months later an event occurred whose significance would be felt for decades to come. Louis Armstrong, the man many still regard as the world’s greatest jazz musician, arrived from Chicago to provide Henderson with great swing, the hottest solos in jazz and greater power in the trumpet section.

‘Smack’ had tried to recruit Armstrong into Ethel Waters’ Black Swan Troubadours when he heard the young cornetist in New Orleans, but Henderson’s and Waters’ loss was King Oliver’s and Chicago’s gain. Yet, the fact that Henderson had finally got his man, was not warmly welcomed by all of Henderson’s musicians. Fletcher’s sidemen prided themselves on being excellent readers, able to produce immaculate performances of written arrangements at first sight and capable of reproducing those perfect performances night after night.

Despite their time in studios with blues singers, Fletcher’s musicians probably felt ‘The Blues’ were beneath them and improvisation did not figure highly among their musical aspirations. They wanted to be better at doing what successful white musicians were doing. New York’s musical values weren’t Chicago’s. That the poorly dressed upstart from New Orleans via Chicago’s Lincoln Gardens got Henderson’s sophisticates to question their musical values speaks volumes about Armstrong’s talent and its appeal.

Armstrong also recommended a clarinettist who doubled on alto, who would become one of Smack’s most loyal sidemen, Buster Bailey, which meant that for a while Henderson had the finest reed section in New York: Redman, Hawkins and Bailey.

Armstrong stayed with Henderson for a little over one year, but Henderson would carry on from strength to strength. Henderson and Redman were producing great arrangements, and, despite Smack’s shunning the spotlight, the Henderson Orchestra would be recognised as the finest black orchestra in New York until near the decade’s end.

The Decline in ’29

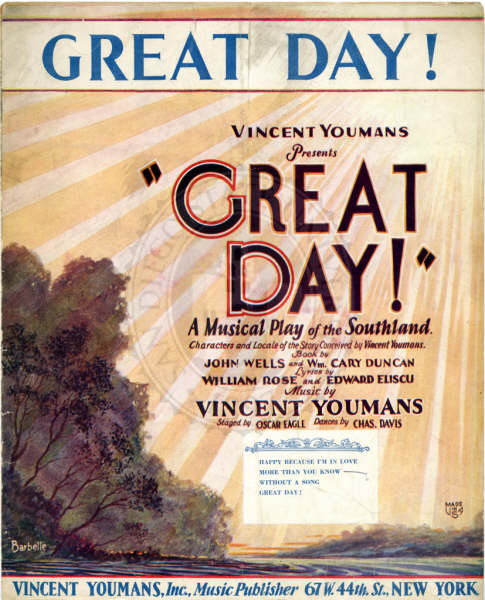

Jerome Kern’s Showboat was such a success on Broadway in the late 1920s that it was bound to inspire some kind of duplication. Vincent Youmans and his backers thought the way was now open for an extravagant musical with a racial theme, a multi-racial cast, with great new songs, top-flight dancers and the Duke Ellington Orchestra. The musical would be called Horseshoes. At some point Ellington and His Orchestra were dropped from the plans, though Irving Mills, the Duke’s manager, prevented this resulting in any adverse publicity for Ellington. The replacement for the Duke and his men was the Henderson Orchestra with Fletcher conducting. (It was rumoured he was taking conducting lessons in order to bring legitimacy to his performances.) Louis Armstrong, now billed as ‘The World’s Greatest Cornet Player’, was also going to join the show.

Unfortunately, all did not go well. Some of Henderson’s musicians were sacked and white musicians were brought in as replacements. Someone proposed that Armstrong occupy not the first, but the second trumpet chair and he seems to have been allocated just one solo spot in the show. Armstrong quickly left. At some point it was agreed that a string section had to be added to the orchestra and, despite musicians of many hues being available in New York, an all-white string section was assembled.

Henderson’s remaining musicians were eventually fired or quit, and Henderson was replaced by a white conductor. Under a new name, Great Day, Youmans’ musical finally made it to Broadway, where it ran for only thirty-seven performances and closed on 16th November, 1929. Showboat ran for five-hundred and seventy-two performances on Broadway and three-hundred and fifty in London’s West End.

Henderson, never one to strive for publicity, was equally reserved when he or his musicians were wronged. It was thought there were clearly times during the rehearsals and comings and goings of Horseshoes/Great Day when Henderson could have been more assertive and put up a fight for the members of his band and for his musical values, but this didn’t happen. Such reticence did not enhance Henderson’s reputation among New York musicians or the Afro American press.

In later years, Fletcher’s wife, Leora, would claim that her husband had been involved in a car accident in Frankfort, Kentucky, in August 1928 in which he sustained serious head injuries and as a result he became “careless” and unconcerned about matters involving his band. This might help explain his seeming indifference to the treatment of his musicians while they were involved with the Youmans’ show. However, in his biography of Fletcher, Jeffrey Magee points out that Henderson’s niece insisted that the injuries sustained in the Frankfort accident were to Fletcher’s collar bone and they were minor. She also suggested that Leora may not have been best placed to report on Fletcher’s condition in 1928, since, at the time of the accident, Fletcher had left his wife and was living with another woman.

Whatever the cause, Fletcher’s lack of concern for his musicians or his own reputation meant that by the end of 1929 he had lost his band and wouldn’t be visiting the recording studios for the foreseeable future. Paul Whiteman and His Orchestra would record the tunes from Great Day. ‘Smack’ and Wall Street had fallen in the same year.

On the way back?

The band that Fletcher took into the recording studios on 9th December 1932 showed that, whatever had happened in the past, he was now moving in the right musical direction. Of course, discipline had never been a strong point with Henderson’s musicians, and for this December date his band arrived late and didn’t manage to complete its four scheduled recordings. But one side was truly outstanding. For many it would become the signature tune of the coming era. The piece, whose origins go back to the days of ragtime, was ‘Jelly Roll’ Morton’s ‘King Porter Stomp’, though on this occasion it was called ‘New King Porter Stomp’. This version consists of a series of solos over riffing saxophones. The solos begin with trumpeter Bobby Stark followed by Coleman Hawkins, tenor, Sandy Williams, trombone, Rex Stewart, trumpet, and the rousing J. C. Higginbottom on trombone. The final chorus features exchanges between the trumpets and the saxes before a high-note finish.

Henderson rerecorded the Morton piece, this time under its original title, on 18th August 1933 with a similar arrangement, though on this new version, after Bobby Stark’s opening solo, there are contributions from a clarinettist, maybe Procope, from Dicky Wells, trombone, from Hawkins, and the gifted and uplifting Henry ‘Red’ Allen, Fletcher’s new trumpet star. These versions of ‘King Porter’ are flag-wavers that put other banners in the shade.

Despite changes in personnel, the most significant being Coleman Hawkins, who left for Europe in March 1934, Henderson carried on leading and recording with outstanding groups of musicians. In September 1934, for example, he made three visits to the recording studios and amongst the reed players he had Buster Bailey, who had enjoyed spells with the band since the time of Armstrong, and Russell Procope and Hilton Jefferson, who would have brought precision and warmth to any sax section. Hawkins had been a principal soloist, but Ben Webster was doing well as a full-toned replacement.

On trumpet, Henry ‘Red’ Allen, whose version of ‘Nagasaki’ recorded with Henderson a year earlier had become Harlem’s ‘national anthem’, sat alongside Russell Smith and Irving Randolph, giving the band an excellent trumpet section. On trombone, Claude Jones and Keg Johnson were both first class musicians, and behind the saxes and brass was the delicate, subtle and unobtrusive drummer, Walter Johnson, who had propelled several of Henderson’s outfits, but never drew attention away from the band’s soloists.

If the individuals were excellent, the recordings made in September 1934 were of similar standing: a staple of the big-band era that was about to grip America, ‘Big John’s Special’, was recorded on 11th September; the next day the band recorded Fletcher’s ‘Down South Camp Meeting’ and ‘Wrappin’ It Up’ alongside a version of Handy’s ‘Memphis Blues’ that had been remodelled by a master arranger. This was a band with arrangements that were creating a distinctive and definitive style.

Those of us who have only heard and been impressed by Fletcher’s studio performances will no doubt be surprised to read, what many have insisted upon, that Henderson’s bands did not play at their best on recordings; apparently they showed their excellence in dance halls and theatres, not in recording studios. All of which leads us to wonder, just how good the band of ‘34 must have been ‘live’. And, yet, superb or not, only a few weeks after making some of its greatest recordings, the band would cease to exist. In November 1934, while playing in Detroit and attracting good audiences, Henderson’s sidemen did not get paid. This was not the first time the band had suffered from poor management. Henderson’s musicians had had enough. Many went to New York to join Benny Carter. “Late 1934 marks a turning point in Henderson’s career”, writes Magee. “Fletcher Henderson was a bandleader without a band.” Would writing for a white band change his fortunes?

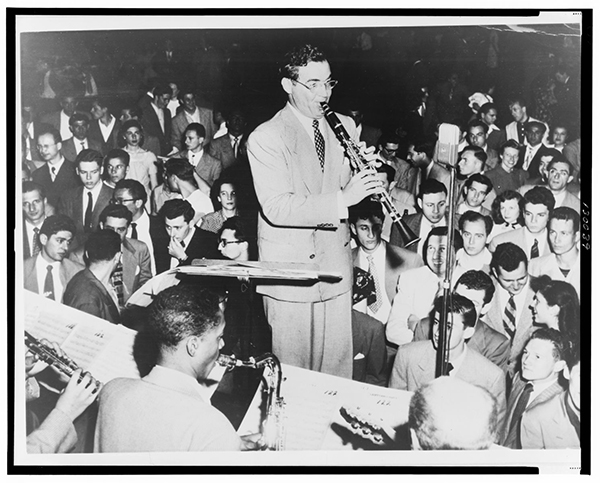

Then came Benny

In late 1934 the well-connected record producer and columnist, John Hammond, approached Fletcher with an offer that Henderson accepted. Fletcher would provide arrangements for Benny Goodman and His Orchestra so that Goodman could produce the “hot” music required for his radio broadcasts. Sometimes Henderson passed on the arrangements he had used with his bands and sometimes, as with Irving Berlin’s ‘Blue Skies’, he would produce something new for Goodman. As a result, on Saturday nights’ ‘Let’s Dance’ programmes Fletcher’s charts would be heard from coast to coast. Henderson was reaching the biggest audience of his life. And Benny? In his biography of Goodman, Ross Firestone, writes: “through no fault of his own, Benny was the beneficiary of a dozen years of experimentation, development and gradual perfection of a style of big band arranging that was to give him the identity he needed.” Maybe all that needs stressing is that the experimentation, the development and the moves towards perfection were principally carried out by Fletcher Henderson.

If ‘Let’s Dance’ provided the ammunition for Goodman’s rise to stardom, the touch paper was lit at The Palomar, a huge ballroom in California on the 21stAugust, 1935. The dancers stopped dancing and flooded round the bandstand when the Goodman band, with Bunny Berrigan on trumpet, started into ‘King Porter Stomp’. Goodman would recall, “I called out some of our big Fletcher arrangements…That first big roar from the crowd was one of the sweetest sounds I ever heard in my life – and from that time on the night kept getting bigger and bigger…”

If Palomar was where the ‘Swing Era’ began, its crowning glory, for many people, came over two years later at Carnegie Hall where Goodman presented something of a cavalcade of jazz, with small groups, guest stars and a jam session, in the famous upmarket auditorium. Included in his programme were several examples of his orchestra playing arrangements by a master: ‘Blue Skies’ arranged by Fletcher Henderson, ‘Blue Room’ arranged by Fletcher Henderson, ‘Sometimes I’m Happy’ arranged by Fletcher Henderson and, as an encore, ‘Big John Special’ arranged by Fletcher Henderson. And, lest we forget, other bands in the Swing Era would use Fletcher’s arrangements: Count Basie, Jimmy Dorsey, Tommy Dorsey, Harry James, Glenn Miller, Artie Shaw, and Chick Webb to name just a few.

Success as an arranger, still didn’t result in success as a leader. In 1936 Henderson was leading a new band with excellent musicians, such as Roy Eldridge and Joe Thomas in the trumpet section and Chu Berry amongst the saxophonists. Again, fame and popularity as a bandleader alluded him and the band broke up. Walter C. Allen, whose book on Fletcher must rank as one of the most thoroughly researched on any jazz musician, writes, “The story that he (Fletcher) disbanded without facing his men in person reflects little credit on him. Perhaps he was too involved in writing arrangements for Benny Goodman, and neglected his own band.” Maybe he had now grown indifferent to failure.

In the years ahead Henderson carried on fronting groups of various sizes, never approaching the success his arrangements achieved when played by others, until, in December 1950, he suffered a stroke. There were stories that he was making a recovery, but another stroke on 29th December 1952 proved fatal.

Fletcher’s status

Louis Armstrong, Coleman Hawkins, Don Redman, Benny Carter, Horace Henderson, Henry ‘Red’ Allen, Roy Eldridge, Chu Berry and others, passed through Henderson’s bands. With this breadth of talent and innovation amongst his sidemen and arrangers, Henderson, according to Magee, acted as “a musical catalyst, facilitator, collaborator, organizer, transmitter, medium, channel, funnel…”. This gives us some indication of the many ways in which Henderson interacted with others, though by concentrating on these dealings and relationships, we could lose sight of Fletcher’s own impact on the world of jazz.

Fletcher’s personal contributions to jazz stretch from being an accompanist to blues singers to being a leader of several superb big bands and an arranger of the most popular music that jazz has ever embraced, and it is for his arranging skills we are most indebted. Walter C. Allen’s appraisal is that Henderson “single-handedly created an arranging style…(that) culminated in what came to be known as “swing” and if any one man can claim to be the Father of Swing as a STYLE , it is Fletcher Henderson.” Several others have reached a similar conclusion, and many have echoed their verdict. As a result, ‘the father of swing’ has become something so routinely said of Henderson, that we may fail to grasp the unique accolade it is. And ‘the father of swing’ is a unique accolade, rightly deserved by a shy, reserved man from Cuthbert, Georgia.

Peter Gardner

February, 2020

Acknowledgements

I am most grateful for the help of Steve Marshall from Marshall McGurk, Maryport, Cumbria, David Nathan, Archivist, National Jazz Archive, Loughton Library, Loughton, Essex, and Sam Gregory, Dawkes’ Woodwind Specialist.

Some sources used

Walter C. Allen, Hendersonia: The Music of Fletcher Henderson and His Musicians (Walter C. Allen, Highland Park, New Jersey, 1973).

Ross Firestone, Swing, Swing, Swing: The Life and Times of Benny Goodman (Hodder and Stoughton, Sevenoaks, Kent, 1993).

Benny Goodman and Irving Kolodin, The Kingdom of Swing (Frederick Ungar, New York, 1961).

Jeffrey Magee, Fletcher Henderson and Big Band Jazz (Oxford University Press, New York, 2005).

Felix Manskleid, ‘Passing Notes on Fletcher Henderson’, Jazz Monthly, December 1957, pp.27-28.

Don Redman, ‘Jazz Composer-Arranger’, Jazz Review, Vol. 2, 1959, pp. 6-12.

Tom Scanlan, The Joy of Jazz; Swing Era, 1935-1947 (Fulcrum, Golden, Colorado, 1996).