‘Ike’s Last Hurrahs’

23rd April 2019Accounts of his short life usually stress he made a promising start to his career as a saxophonist, for in his early years he recorded on numerous occasions and became a principal soloist with the Cab Calloway Orchestra. The second period of his career, which covers most of the 1950s, is seen as a bleak battle with a heroin addiction, few well paid jobs and few recording opportunities. Third, and finally, there is a golden sunset, where our saxophonist was able to make recordings and gave performances that showed him at his best. Of course, real lives are never this simple or so neatly compartmentalised, and Ike Quebec’s was no doubt more complicated than this brief summary suggests, but I also suspect that most who knew Ike would recognise him from the picture we have painted.

Ike Quebec

Big-toned star emerges

Born in Newark, New Jersey, on 18th August, 1918, Ike Abrams Quebec first entered show business as a dancer, and, at the time, was also seen as a talented pianist. It was in his early twenties that he switched his attention to the tenor saxophone and made rapid progress on the instrument. In the early 1940s he played in the bands of Frankie Newton, Roy Eldridge and Benny Carter and between 1944 and 1951 he would work intermittently with the Cab Calloway band.

He was also making records. In July 1944 he was leader of a quintet that recorded for Alfred Lions’ Blue Note label and had a jukebox hit from the session with his own composition, ‘Blue Harlem’. The session also gave us a slow and sensitive version of ‘She’s Funny that Way’. In September, with a group billed as the ‘Ike Quebec Swingtet’ that featured such stars from Cab Calloway’s ranks as Jonah Jones and Tyree Glenn, Quebec was back recording for Blue Note and on ‘If I Had You’, Quebec gives one of his finest early ballad performances. The tempo is slow, Quebec’s tone is rich and full, without any edge or harshness, except in the upper register, where it is demanding and insistent, and Jones and Glenn play exquisite supporting roles. This is ballad playing by musicians who delight in what they are doing.

Another Blue Note session in April 1945 saw Quebec fronting a quintet and showing his solo prowess on both ‘Blue Turning Grey’, taken at a little above medium tempo, and on a slow and serious ‘Dolores’. In July 1945 the ‘Ike Quebec Swing Seven’ had Buck Clayton, trumpet, and Keg Johnson, trombone, sharing frontline duties with the tenor player, and after a rather frantic ‘I Found a New Baby’, Quebec excels on the slow ballad, ‘I Surrender Dear’. A gently swinging ‘Girl of My Dreams’ from a session in August for the Savoy label has Quebec in the company of pianist, Johnny Guarnieri, and bassist Milt Hinton. This is another example of effortless, full-toned tenor playing (1).

Hard times

At a time when the harmonic influence of bebop was affecting not just up-and-coming saxophonists, like Gene Ammons and Illinois Jacquet, but established stars from an earlier period, like Coleman Hawkins, Quebec seemed immune to bop’s harmonic attractions. While Quebec’s model is clearly Hawkins, it is not the Hawkins who tried to embrace the harmonics of Gillespie and Parker. Quebec’s hero is very much a man of the swing era with the addition of the rougher edges of tenor saxophone playing that the 1940s helped bring to the fore.

Another of bop’s enticements seemed to have little impact on the young Quebec. But, then, as Dexter Gordon observed, reflecting on his own addiction, “…there were a lot of cats that started later. That’s another thing that surprised me. Cats who had seen us go through this…I’m talking about older guys like Ike Quebec and other guys over thirty already. Even Jug (Gene Ammons)…”

Fortunately Quebec, unlike many, was not killed by his addiction, although “…the casualty list in the fifties …started to look like the Korean War was being fought at the corner of Central and 45th” was Hampton Hawes’ assessment of the impact of drugs on the New York jazz scene. Those who managed to live with their addictions could still end up in penitentiaries. When Gene Ammons was charged for the second time, he was originally looking at a sentence of fifteen years to life. He eventually served seven years (2).

Quebec survived and stayed out of prison, but, as Leonard Feather would have it, “during the 1950s he was virtually inactive in jazz”. Indeed, Richard Cook has written that “by the middle of the decade he was driving a taxi”.

Blue Note’s golden times

Berlin-born Alfred Lion founded Blue Note records in 1939. Quebec had already recorded for the label in the 1940s and in 1959, with Quebec back playing and sounding like a throwback to an earlier style, Alfred Lion thought that Quebec might have a suitable sound for the jukebox market. Lion also valued Quebec’s views on which musicians Blue Note should recruit. Before long, Quebec was a valuable part of the company.

Quebec’s first comeback album, ‘Heavy Soul’, was recorded in Rudy Van Gelder’s New Jersey studio on 26th November, 1961. Accompanied by Freddie Roach, organ, Al Harewood, drums, and a bass player with whom he had played during his time with Cab Calloway, Milt Hinton, ‘Heavy Soul’ finds Quebec specialising in ballads like ‘Just One More Chance’, ‘Brother Can You Spare a Dime?’ and ‘I want a Little Girl’. This was perfect material for Quebec’s warm, enveloping tone. “3 a.m. uptown bar music” is Leonard Feather’s description, and even the title track, ‘Heavy Soul’, a twelve bar by Quebec, keeps to a small-hours tempo and mood.

Ike Quebec – ‘Heavy Soul’ Blue Note Records

On 9thDecember Quebec was again recording in Van Gelder’s studio in New Jersey with Roach, Hinton and Harewood. This album would be called ‘It Might As Well Be Spring’. In addition to the title track, the ballads included ‘Lover Man’ and ‘Willow Weep For Me’, and there was a spirited ‘Ol’ Man River’ that has Quebec at his most extreme, though extreme Quebec is well within most listeners’ tolerance levels.

What many writers regard as Quebec’s finest performance came a week later. In the company of two of Miles Davis’ sidemen, Paul Chamber, bass, and Philly Joe Jones, drums, and with guitarist Grant Green instead of a keyboard player, Quebec tackled the Count Basie tune from 1938, ‘Blue and Sentimental’, which became the title track of his third album for Blue Note. As if honouring the legacy of Herschel Evans and Lester Young, Quebec and Green treat the Basie standard with considerable sensitivity. Only in the last chorus, with the familiar riff from Basie’s original, do they approach full power before returning to their restful and respectful ways. Another haunting tune on this rightly acclaimed album is one I associate with Artie Shaw’s final small groups, it is Henry Nemo’s, ‘Don’t Take Your Love From Me’. Quebec’s performance on this sadly neglected ballad is one of rich-toned delicacy.

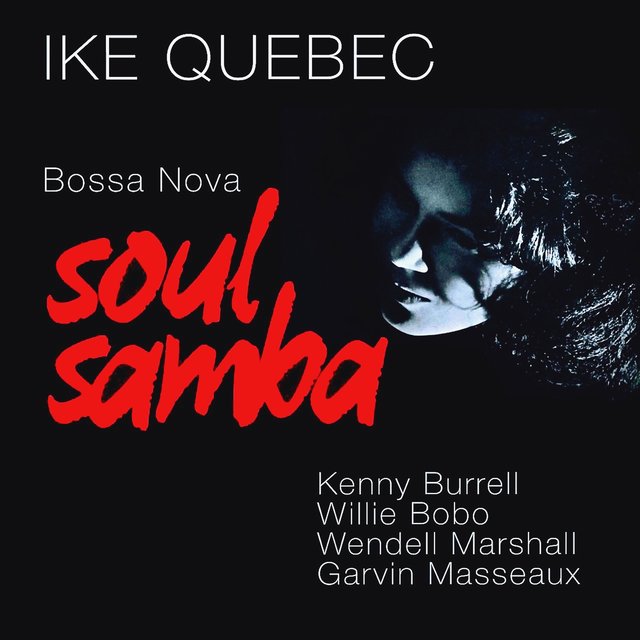

The album ‘Bossa Nova Soul Samba’ was recorded in October 1962. It features Kenny Burrell, guitar, Wendell Marshall, bass, Willie Bobo, drums, and Garvin Masseau, percussion, and has some of the quietest playing of Quebec’s recording career. Dvorak’s ‘Going (but spelt Goin’) Home’ and Liszt’s ‘Liebestraum’ may seem odd choices, but with a gentle bossa beat, they are perfect vehicles for Quebec’s softly pressing saxophone. Easily thought of as an attempt to cash in on what was then the current craze, this is actually a most satisfying album.

Ike Quebec – ‘Bossa Nova Soul Samba’

“a memorial which should be better known”

By the time he came to record these four albums Quebec, as Richard Cook maintains, “had himself matured into a musician of almost apologetic grandeur …his records garnered little attention, yet remain enormously satisfying examples of Blue Note’s releases in the period…They were unambitious records, filled with standards and blues, and the most striking thing about them is the preponderance of slow tempos: most Blue Notes were upbeat for most of the time, but Quebec took a different path…His brief sequence of albums is a memorial which should be better known and acknowledged.”

He may have been out of kilter with what the hardish boppers, modal improvisers and free jazzers of the day were doing, but he was true to himself; he produced music that was relaxed, deeply satisfying and never dull. Unfortunately his golden sunset didn’t last long. Ike Quebec died from lung cancer on 16th January, 1963. He was only forty-four years old.

Peter Gardner

April, 2019

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Steve Marshall, Marshall McGurk, Maryport, Cumbria, and Dawkes’ woodwind specialist, Sam Gregory.

Endnotes

(1) All of the recordings mentioned up to this point can be found on ‘A Proper Introduction to Ike Quebec: Blue Harlem’, INRO CD 2004.

(2) See my “Jug”, Dawkes Newsletter, February 2019.

(3) All four of the Blue Note albums that I have mentioned, ‘Heavy Soul’, ‘It Might As Well Be Spring’, ‘Blue and Sentimental’ and ‘Bossa Nova Soul Samba’, but without any additional tracks that may appear on individual CDs of these albums, are on the double CD ‘Ike Quebec: Four Classic Albums’, Avid Jazz, AMSC 1322. This double CD is competitively priced and is highly recommended.

Some sources used

Richard Cook, Blue Note Records: The Biography (Pimlico, London, 2003).

Ira Gitler, Swing to Bop (Oxford University Press, New York, 1985).

Hampton Hawes and Don Asher, Raise Up Off Me (Thunder’s Mouth, New York, 1974).

Bob Porter, Soul Jazz (Xlibris, Milton Keynes, 2016).

Harry Shapiro, Waiting for the Man (Helter Skelter, London, 1999).