‘Jaws’

23rd February 2018“I didn’t buy an instrument for the sake of the music…I wanted the instrument for what it represented. By watching musicians I saw that they drank, they smoked, they got all the broads and they didn’t get up early in the morning. That attracted me. My next move was to see who got the most attention, so it was between the tenor saxophonist and the drummer. The drums looked like too much work, so I said I’ll get one of those tenor saxophones. That’s the truth.”

Whether playing the saxophone brought the results he hoped for is not recorded. What we do know is that even if he only saw playing the tenor saxophone as a means to an end, Eddie Davis or, to give him the name he had for much of his career, Eddie ‘Lockjaw’ Davis would become one of the most recognisable and one of the most musically muscular of tenor players.

As for the nickname ‘Lockjaw’, whether it came from the way he gripped his tenor’s mouthpiece or from the title of one of his early recordings has been a matter of debate, but the nickname and its abbreviation ‘Jaws’ certainly stuck.

‘Lockjaw’ seems to have been a man of natural authority and considerable self-confidence. For several years he worked at Minton’s Playhouse, a club enshrined in jazz folklore for its fearsome jam sessions and its role in the emergence of bebop. But he wasn’t just Minton’s resident tenor player; the manager of Minton’s, Teddy Hill, found it difficult to manage both the club and its bandstand, so ‘Lockjaw’ had what he called the “policeman’s job” of making sure that those musicians, who couldn’t cut the mustard, (kindly?) left the stage. If his policing Minton’s showed his authority, one of ‘Lockjaw’s’ earliest encounters with Count Basie speaks volumes about his self-confidence. The Basie orchestra was playing at the Savoy Ballroom in New York and ‘Lockjaw’, as Basie recalled, who was keen to join the Count’s band, would sit “right there behind me…near where the piano was” and he “kept saying, ‘You need me in this band.’ And I said, ‘No, I don’t. I don’t need nobody.’ But he’d say, ‘You need me in there.’” Later in his career, when Lockjaw was enjoying one of his longer spells with Basie, he was also the road manager for the band, and he proved to be one of the best Basie ever had. “He was tough, but he was fair. And he was honest…But he could get pretty rough…He wouldn’t stand for any stuff from anybody.”

In the arts the relationship between the work of art and the personality of the performer or creator is not simplistic, and the art of jazz is no exception; some of the most moving, sensitive and heartfelt playing in jazz has come from individuals who, by most accounts, could be nasty, brutish and distinctly short of those qualities that make someone warm, kind and approachable. However, with ‘Lockjaw’ I’m sure you heard the man; he played with authority and confidence (“I deliberately handle the horn the way I do, to show I’m its master!”) and, to borrow from Basie, with roughness, toughness and honesty.

Born in New York in 1922, Davis bought a tenor sax in his late teens, and, though he was mainly self-taught with the aid of an instruction book, he was playing professionally in a matter of months. Spells with the bands of Cootie Williams, Lucky Millinder, Andy Kirk and Louis Armstrong preceded his long residence at Minton’s. His early influences were tenor players from the swing era, like Coleman Hawkins and Ben Webster, but Bop and R & B would also have an impact on his style. By 1958 he was enjoying his second spell with Count Basie and he featured on what was surely one of the best big band albums of the first LP era. (Apparently another LP era is underway at present.) ‘The Atomic Basie’ consisted of eleven pieces by Neil Hefti and ‘Lockjaw’ solos magnificently on several tracks. He is deliciously Websterish on the bluesy ‘After Supper’, aggressive on ‘Flight of the Foo Birds’ and even more pugnacious when he solos at greater length on ‘Double-O’. But his supreme moment, I would contend, is on ‘Whirly Bird’. He enters like a lion, not frantic, just menacing and in complete command. You know this is someone who “wouldn’t stand for any stuff from anybody”.

During the 1950s ‘Lockjaw’ also helped initiate a trend that would attract many followers; he started to play in small groups, normally trios, that featured organists usually playing the Hammond B-3 organ. Tenor-organ groups became a staple of soul jazz and one of ‘Lockjaw’s’ most famous trios had the young Shirley Scott at the keyboard and pedals and Arthur Edgehill at the drums. In 1958, after he had left Basie, ‘Lockjaw’ along with Scott and Edgehill, and with the addition of George Duviver on bass and Jerome Richardson on flute, recorded two albums, ‘Eddie ‘Lockjaw’ Davis Cookbook’, Volumes 1 and 2. Blues that rock or move seductively are prominent in the Cookbooks, but so are ballads: ‘But Beautiful’, ‘Stardust’ and ‘I Surrender Dear’ are three of the ballads that ‘Lockjaw’ treats with respect and delicacy, though you always know that hollers and a scream or two are lying in reserve

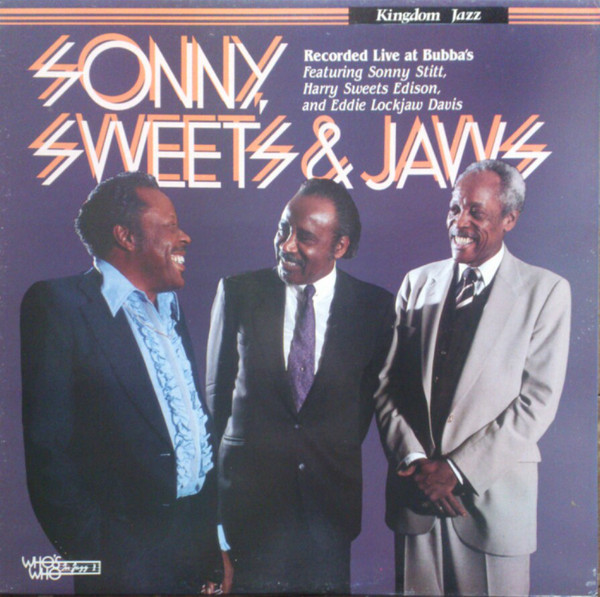

In 1960 ‘Lockjaw’ joined forces with ‘The Little Giant’, aka ‘The Fastest Tenor in the West’, the unquenchable Johnny Griffin, to form a group frequently referred to as ‘The Tough Tenors Quintet’. The group recorded several notable albums for both Jazzland and Riverside, two of the earliest being ‘Battle Stations’ and ‘Tough Tenors’ which, it is tempting to say, did exactly what they said on the labels, though, in fact, the two horn players didn’t battle, but inspired one another, albeit robustly. In the early sixties ‘Lockjaw’ also shared frontline duties in clubs and the recording studio with the fearsome Sonny Stitt. If anything bears testimony to ‘Lockjaw’s’ talent and the dependability of his own style, it is that he shared stages, spotlights, studios and microphones with both Griffin and Stitt, two sax players who would walk over anyone with a weakness, and ‘Lockjaw’ was never bettered and never deviated from his own distinctive brand of virile tenor. As Scott Yanow observed, ‘Lockjaw’ “could hold his own in a saxophone battle with anyone”.

Just a few weeks after making ‘Battle Stations’ with Griffin, ‘Jaws’ was the featured soloist on an album that several critics have singled out for high praise. Recorded in September 1960, ‘Trane Whistle’ involves a big band playing originals and charts by the emerging and immensely talented Oliver Nelson plus two arrangements by Ernie Wilkins. The following year, on Nelson’s rightly famous album ‘Blues and the Abstract Truth’, his composition ‘Stolen Moments’ would receive its definitive treatment. On ‘Trane Whistle’ the tune was heard for the first time on record, though for its first appearance it was called ‘The Stolen Moment’, with ‘Lockjaw’ soloing at length over some gentle prompting from the brass section.

The quintet with Griffin toured and recorded extensively, but poorly paid bookings led to its demise in 1962 and by 1963, ‘Jaws’, by his own admission, was feeling stale. At this point in his career he gave up playing and became a booking agent, often booking bands and soloists into the very clubs where he had previously played. Yet, playing still had a pull and by the mid 1960s he was back playing with Basie where with various breaks, he would stay for the next eight years or so. During one break he was in Europe with the outstanding Kenny Clarke-Francy Boland Big Band playing alongside Johnny Griffin during another break in 1970 he played with Griffin and the Clarke-Boland band’s rhythm section on an album recorded in Cologne called ‘Tough Tenors Again ’N’ Again’.

After Basie ‘Lockjaw’ pursued what Cook and Morton refer to as “the journeyman route of wandering freelance” through what remained of the ‘70s and the early ‘80s. Frequently he paired up with trumpeter Harry ‘Sweets’ Edison, the two horns often engaging in what Cook and Morton call the “good cop/bad cop routine”. No prizes for guessing who the bad cop was. One of my favourite ‘Lockjaw’ performances comes from this later period in his career. It was recorded in Zurich’s Widder Bar in March 1982. With Gustav Csilk on piano, Isla Eckinger on bass and drummer Oliver Jackson, and before what sounds like a small audience, ‘Jaws’ tackles the Vernon Duke/Ira Gershwin standard ‘I Can’t Get Started’ (1). He begins with a crowd–grabbing introduction, which is followed by a very slow and at times breathy ballad performance topped off with a coda that ends with a scream. This is ballad-playing with muscles.

It is said that Eddie ‘Lockjaw’ Davis appeared on over five hundred albums as leader, co-leader or sideman. He was an active musician until the September of his final year, but in November 1986, he died of cancer. He was sixty-four years old, though some obituaries said he was sixty-five. During his life-time many big-toned tenor players had appeared on the jazz scene – Illinois Jacquet, Arnett Cobb, Gene Ammons, Red Holloway, King Curtis, Plas Johnson, Stanley Turrentine are just a few that come to mind – , but none was as readily identifiable as ‘Lockjaw’.

Jazz has come a long way – from funeral processions and funky butt halls to conservatories and the ivy covered walls of academia – and this respectability has brought standardised sounds for jazz’s instruments. Bechet’s vibrato, Johnny Dodds’ edge, Pee Wee’s growls, Pete Brown’s staccato stridency, Webster’s breath and ‘Lockjaw’s’ punch, hollers and screams may all be outside to-day’s prescribed norms. Musical legitimacy can threaten individualism and make us less receptive to jazz’s diversity. So, before you wet another reed and try to produce an exam-board-approved tone, rebel a little; go and listen to ‘Lockjaw’. He was staggeringly original and also very, very good.

Peter Gardner

February, 2018.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Dawkes’ woodwind specialist, Sam Gregory, and to Steve Marshall from Marshall McGurk, Crosby, Maryport, Cumbria.

Endnote

(1) I hope this single endnote has some useful information about CDs that contain the recordings, tunes and albums that I have mentioned. ‘After Supper’, ‘Flight of the Foo Birds’, ‘Double-O’ and ‘Whirly Bird’ are all on ‘Count Basie/The Complete Atomic Basie’ Roulette 7243 8 28635 2 6. The two ‘Cookbook’ albums I have mentioned are ‘The Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis Cookbook’, Vol. 1, OJC20 652-2 and ‘The Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis Cookbook’, Vol. 2, OJCCD 653-2. Several albums by the Davis/Griffin Quintet can be found on the four CD collection ‘Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis/Johnny Griffin Quintet, The Complete Sessions’, Jazz Dynamics 001. (The use of ‘Complete’ in the title for this collection needs some qualification.) ‘Lockjaw’ can be heard with Stitt on ‘Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis & Sonny Stitt, Jaws & Stitt at Birdland’, CDP 7975072. ‘The Stolen Moment’/’Stolen Moments’ is on ‘Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis Big Band, Trane Whistle’, OJCCD 429-2. ‘Lockjaw’ with the Clarke/Boland band can be heard on ‘The Kenny Clarke/Francy Boland Big Band, Two Originals’, MPS 0979. The Davis-Griffin Quintet with the rhythm section from the Clarke/Boland Big Band appears on ‘The Eddie Lockjaw Davis-Johnny Griffin Quintet, Tough Tenors Again ’N’ Again’, MPS 441182. ‘Lockjaw’ and Harry Edison can be heard on several CDs, including ‘Edison’s Lights’, OJC 804 and ‘Harry ‘Sweets’ Edison/Eddie ‘Lockjaw’ Davis’, Storyville 8225. The version of ‘I Can’t Get Started’ from March 1982 that I refer to can be found on ‘Eddie ‘Lockjaw’ Davis, Live at the Widder’, Vol. 1, Divox CDX 48701. An impressive three CD collection is: ‘Eddie ‘Lockjaw’ Davis, 80th Birthday Celebration’, 35 Classic Prestige, Pablo, Jazzland and Riverside Recordings, Fantasy FANCD 6063-2. If you want a quick fix of ‘Lockjaw’ go to YouTube and watch him in 1965 soloing with the Count Basie Orchestra on ‘Jumping at the Woodside’.

Some sources used

Count Basie, Good Morning Blues: The Autobiography of Count Basie as told to Albert Murray (Heinemann, London, 1986).

Richard Cook and Brian Morton, The Penguin Guide to Jazz Recordings, Eighth Edition (Penguin Books, London, 2006).

Stanley Dance, The World of Count Basie (Sidgwick & Jackson, London, 1980).

Mike Hennessey, The Little Giant: The Story of Johnny Griffin (Northway, London, 2008).

David H. Rosenthal, Hard Bop: Jazz and Black Music, 1955-1965 (Oxford University Press, New York, 1992).

Arthur Taylor, Notes and Tones, Expanded Edition (Da Capo, New York,1993).