John Hammond’s ‘From Spirituals to Swing’

10th August 2018Most of his biographers mention that he found some very talented performers and brought them to the attention of wide and appreciative audiences. Count Basie, Billie Holiday, Charlie Christian, Aretha Franklin, Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen are just some that get named as being amongst his ‘discoveries’.

That he was a descendant of Cornelius Vanderbilt, therefore heir to part of the Vanderbilt fortune, and a tireless fighter for the rights of African Americans are also items his biographers are quick to bring to their readers’ attention. That he was a record producer, a Yale drop-out, that one of his sisters married Benny Goodman, ‘The King of Swing’, having been first married to an English Conservative Member of Parliament, that he was born in 1910 in a house near New York’s Central Park that had sixteen servants and its own ballroom are other items that might find their way into the biographical mix.

Deeper research might reveal that his first and life-directing experiences of jazz were not in his native city, but during a trip to London with his parents in the early 1920s, where he heard both Jimmy Dorsey, Tommy’s brother, playing with a group in a Lyon’s Corner House, and the New Orleans powerhouse, Sidney Bechet, playing in a West End theatre. Yet, what some biographers of John Hammond fail to mention is that in the late 1930s, when the Swing Era was in full flow and Swing was seen as something new, Hammond was committed to showing that Swing had roots, particularly African American roots, and he was determined to bring jazz history and jazz’s diversity to what he called “a musically sophisticated audience”. And you would be hard pressed to find an audience more musically sophisticated than at New York’s Carnegie Hall.

John Hammond

Following the success of Benny Goodman’s Carnegie Hall Concert in January 1938 when, to borrow from the music press of the time, swing invaded “the sanctum of the long-hairs”, John Hammond decided that the same venue would suit his purposes. But the cost of putting together the cast he had in mind, meant that he needed sponsorship. (I take it his family were not interested in helping its errant offspring’s wild venture.) The NAACP, The National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People, might have seemed an obvious sponsor, but, as Hammond wrote later, “Jazz and, particularly, primitive black music were not too familiar to the middle-class leaders of the NAACP to be anything they could take pride in.” Eventually Eric Bernay, business manager for New Masses, a weekly writers’ and arts publication financed by the Communist Party of America, agreed to sponsor Hammond’s dream. The concert would be called ‘From Spirituals to Swing’, it would be held on Friday, 23rd December, 1938, and it would be dedicated to Bessie Smith, the Empress of the Blues, who had died one year earlier. All of the performers would be African Americans or, to use the term that was employed in those days, Negroes. Hammond’s wish that the Carnegie evening was not to be used for propaganda purposes seems to have been well respected, though inside the cover of the concert’s programme is an appeal that reflects the stance of New Masses in those troubled times: it is for donations to help ease the suffering of nearly four million children “in Loyalist Spain” who are “the victims of Fascist aggression”.

According to the programme for the December evening, the first section of the concert would be devoted to Spirituals and Holy Roller Hymns. Having heard great reports about a vocal group in Kinston, North Carolina, Hammond went to check it out. The Mitchell Christian Singers were a vocal quartet that took its name from one of its original singers, William Mitchell, but he was no longer a member of the group. Hammond visited Kinston and, as he would later write, found the quartet “in a backwoods shack with no running water and no electricity” and was sure that no white person had ever set foot in their house. Having heard the quartet Hammond insisted “there could not be a concert without the Mitchell Christian Singers.” Twenty-three year-old Sister Rosetta, who had spent most of her life singing and playing guitar in churches, was also recruited for the Spirituals section. Later and better known as Sister Rosetta Tharpe, she would cross over into blues and jazz and be viewed as ‘the original soul sister’ and ‘the godmother of rock and roll’.

In the Blues section of the concert Hammond wanted to feature Blind Boy Fuller, but it turned out that Fuller was in jail for trying to shoot his wife. (“Blind Boy had managed by standing in the centre of a room, rotating slowly, and firing intermittently – fortunately missing” was how Hammond described the failed attempt.) Luckily, while trying to track down Fuller, Hammond came across a blind harmonica player and vocalist with his own unique talents, Sonny Terry, who later in life would form an immensely popular duo with Brownie McGhee. Blues singer Robert Johnson, whose recordings would have such an influence on rock and blues performers in the 1960s, was also wanted for the Blues section, but as Hammond noted in the concert’s programme, Johnson died at just about the time he heard “that he was booked to appear at Carnegie Hall on December 23. He was in his middle twenties and nobody seems to know what caused his death.”

Other singers recruited for their blues contributions included Ruby Smith, often thought to be related to Bessie Smith, Big Joe Turner, who dispensed with a microphone and still filled every nook and cranny of the Carnegie auditorium, and Big Bill Broonzy, rightly described as “one of the most important figures in the history of recorded blues.” To this impressive trio were added two vocalists from the Count Basie Orchestra, Jimmy Rushing and Helen Humes. Clearly Hammond had covered many bases of the blues with outstanding performers.

Even more impressive were the pianists assembled for the Boogie-Woogie section of the concert. They were the three kings or the three masters of Boogie-Woogie: Albert Ammons, Meade ‘Lux’ Lewis and Pete Johnson. James P. Johnson, often seen as the father of Harlem stride and a revered composer, was also amongst the piano stars Hammond assembled.

James P. Johnson – Pianist

The legendary Sidney Bechet on soprano sax and clarinet and trumpeter Tommy Ladnier, who, as recent research has shown was born not far from what is often viewed as jazz’s birthplace, were part of a front line for the concert’s Early New Orleans section.

For Swing there was Count Basie and His Orchestra. At that time Basie had outstanding soloists everywhere you looked: Buck Clayton and Harry Eddison frequently vied for solo space amongst the trumpeters; trombonists Dickie Wells, Dan Minor and Benny Morton all had their individual contributions to make; and in the reed section Herschel Evans and the revolutionary Lester Young were probably the best pair of tenor saxophonists that any band ever had. If the band’s horn players were outstanding, its rhythm section was simply off the scale. Later to be publicised as the All American Rhythm Section, Jo Jones, drums, Freddie Green, rhythm guitar, and Walter Page, bass, along with Count Basie, piano, could provide everything from a gently swinging cushion to fearsome propulsion. No band in the Swing Era had a rhythm section to match Bill Basie’s. To add to the excitement, for part of its performance the Basie orchestra would be accompanying a trumpet star who had played with the band in its Kansas City days, Oran ‘Hot Lips’ Page.

The concert for December 1938 was sold out and three-hundred of the integrated audience had to be seated on stage. A photograph of the event shows Walter Page and Jo Jones flanked by members of the audience, as if they are waiting to take over from the Basie sidemen. The same photograph shows that most of the women, as in church services at the time, are in hats. Despite reports of chaos backstage, the music flowed for three and a half hours ending with the Basie band in full flow.

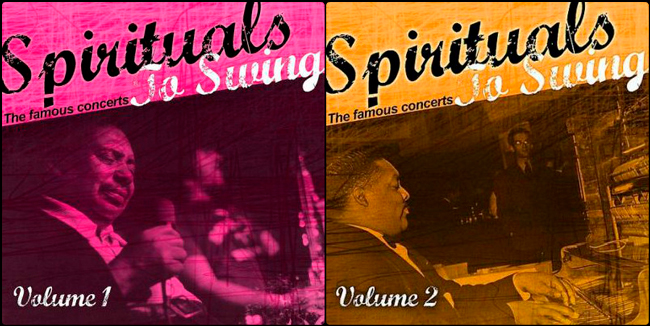

Hammond organized a second From Spirituals to Swing Concert on 24th December, 1939, and arranged for both concerts to be recorded. In the 1930s recording involved using acetate discs and in the 1950s the original recordings were transferred from the acetates to tape. In 1959 Vanguard issued a two LP set of the concerts and a double CD set followed in 1987, but later research discovered more material and in 1999 a 3 CD boxed set was issued (1). However, these recordings have to be treated with a certain degree of caution; noble though his intentions as a concert promoter might have been, Hammond was not above a bit of fakery when it came to ‘recordings’ from his famous promotions. Interspersed amongst the original tracks from the 1938 concert are several recordings made in a studio in June 1938 featuring Basie-led small groups complete with added applause. Also included on the LPs and CDs are some spoken introductions from Hammond that seem to come from the Carnegie Hall evenings. But these were actually recorded in the 1950s, with Hammond’s voice raised a tone or two by Vanguard’s engineer to make him sound younger, and seamlessly added. To his credit, though a little belatedly, in an interview in 1971 Hammond came clean about some 1938 studio recordings being made to sound like concert performances and about the late addition of his spoken contributions.

Sidney Bechet – Saxophonist

Nevertheless, the genuine recordings from the 1938 concert are mightily impressive, with only the Bechet-Ladnier group appearing overawed by the occasion as they rush through their numbers. The contribution by Mitchell’s Christian Singers makes one realise why Hammond saw them as essential to the evening. Later, when two grand pianos and an upright were pushed on stage, the audience must have wondered what it was about to receive. Ammons, Lewis and Pete Johnson soon let them know. ‘Cavalcade of Boogie’ which features the three pianists plus Walter Page and Jo Jones would make any audience rock, even a long-haired one. The original recordings of Basie from December 1938 show a band at its peak. On ‘Swinging the Blues’ the section work is precise perfection and soloists Lester Young, Buck Clayton, Herschel Evans and Harry Eddison respond accordingly. When ‘Lips’ Page takes his solo spot, the Basie sidemen riff their mighty encouragement behind him’ and on the frantic ‘Every Tub’ the band simply takes off., and, in the words of one commentator, Basie’s musicians left “the audience gasping at the spectacle of powerful talent let loose.”

The review of the 1938 concert that appeared in New Masses in January 1939 detailed not only the evening’s achievements, but spoke of the oppressive and much darker times on which the concert’s music shed light and over which it triumphed:

It is difficult enough to draw an attendance of three thousand, to achieve exciting and

commendatory comment from the daily and weekly press, to hold an audience spell-

bound – all of which the concert did; but to top this it gave a lesson in the history of

American music; to use a dread word, it educated. It marked the close alliance

between the music made in the everyday life of the Negro and the music which has

come to be called swing ; it maintained an authenticity which served as a crushing

indictment of commercial jazz with all its attendant chicanery and lack of sincerity;

and finally, it proved that an instinctive love of music will break through the thickest

fog of oppression, and with lightning speed and irrefutable argument, record that

oppression.

If John Hammond’s 1938 concert had achieved half of this, it would have been a resounding success. And it most certainly was.

Peter Gardner

Summer, 2018

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Steve Marshall, from Marshall McGurk, Crosby, Maryport, Cumbria, and Sam Gregory, Dawkes’ woodwind specialist.

Endnote

(1) Vanguard, ‘From Spirituals to Swing’, 3 CD Set, 169/71-2, originally issued in 1999.

Some sources used

John Hammond with Irving Townsend, John Hammond on Record (Penguin, Harmondsworth, 1977).

Bo Lindstrom and Dan Vernhettes, Traveling Blues: The Life and Music of Tommy Ladnier (Jazz Edit, Paris, 2009).

Robert Walser, Ed., Keeping Time: Readings in Jazz History (Oxford University Press, New York, 1999).

Vanguard, ‘From Spirituals to Swing’, 3 CD Set, 169/71-2, 1999.