Jug – Gene Ammons

19th February 2019“When I heard (Gene) Ammons play that saxophone, I knew that I was going to become a saxophone player. There was no doubt in my mind about it.”

Johnny Griffin

“His big sound and driving beat established him as one of the giants of modern jazz saxophone.”

Leonard Feather and Ira Gitler

In August 1947 Albert Ammons, whose business card read, “Albert C. Ammons – King of Boogie Woogie”, went into a Chicago studio to record for the Mercury label. As he had done off-and-on during his career, Ammons would be recording with a group named as ‘Albert Ammons and His Rhythm Kings’, and guitarist, Ike Perkins, and bassist, Israel Crosby, who were part of the ‘Rhythm Kings’ when the group first recorded in 1936, would be part of the 1947 ensemble. But the twenty-two year-old tenor saxophonist was new to the group. The tenor player was Albert’s son, Gene.

Albert, Edsel and Gene

Albert Ammons, seen by several authorities as the greatest of all Boogie-Woogie pianists, was born in Chicago in 1907. While still in his teens he married Lila Mae Sherrod, a gifted pianist and singer, and their first son, Edsel Albert Ammons, was born in February 1924. A year or so later, on 14th April 1925, their second son, Eugene, shortened to Gene, was born. Edsel would achieve great things: he graduated from Roosevelt University in Chicago, he would go on to pursue postgraduate qualifications in Theology, he would become a deacon and an elder in the African Methodist Episcopal Church and in 1976 he would become Bishop of America’s United Methodist Church. Bishop Edsel Ammons died on Christmas Eve in 2010 aged eighty-six. His father and his younger brother, Gene, would lead altogether different and much shorter lives.

By the time he recorded with his father in August 1947, Gene Ammons had already fallen under the spell of Lester Young. Yet, unlike many of the aspiring tenor players who were attracted to Lester’s melodic way of improvising, Gene did not use a light, dry sound; Gene’s sound was big, rich and round. It owed more to Hawkins, Webster and Don Byas than Lester. The yelps and screams associated with Illinois Jacquet had also found there way into Gene Ammons’ tenor playing, as he made clear when he soloed on ‘S. P. Blues’ with his father’s ‘Rhythm Kings’ (1). Sadly, less than three years later, his father was dead. Albert Ammons was only forty-two when he died. Hard drinking and the ups and downs of the jazz life had taken their toll.

Albert Ammons – Piano

An emerging star and convict

Before playing with his father, Gene Ammons had spent three years with the Billy Eckstine Orchestra alongside such trail-blazing modernists as Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, and two months before his session with the ‘Rhythm Kings’, he had recorded with his own sextet. That session produced a minor hit, ‘Red Top’, with Gene beginning his solo with a quote from ‘Alice Blue Gown’. (On ‘Idaho’ from the same session, Gene begins his solo with a quote from Dvorak’s ‘Humoresque’. Quotes, it seems, were in.) In the late ‘40s Gene was also involved in numerous tenor battles with players on the Chicago scene and, according to Bob Porter, “never lost a match.” This was “the era when the legend of Gene Ammons grew in his own hometown.”

During his time with Eckstine, Gene Ammons also acquired a nickname that would be used for the rest of his life. Eckstine called Gene ‘Jug-head’ when he heard of Gene’s hat size. Abbreviated to ‘Jug’, it stuck.

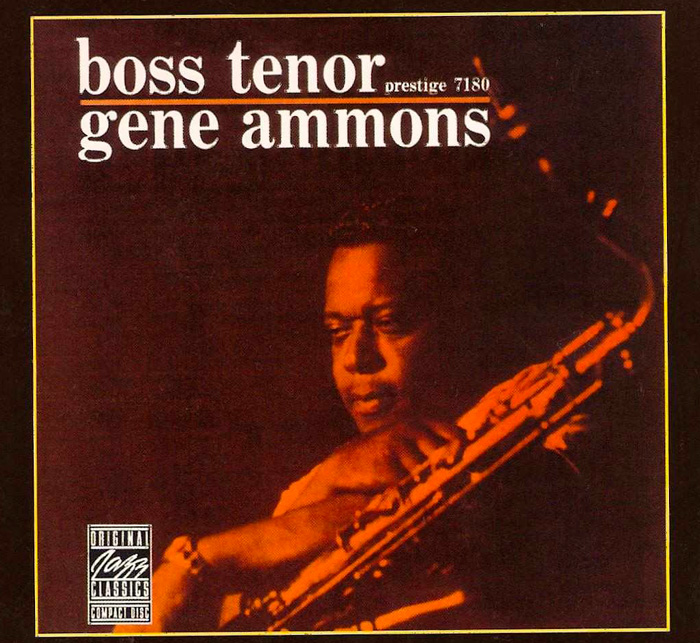

The 1950s was an eventful time in Jug’s life. He had another minor hit with what has been described as a “fulsomely romantic rendition” of ‘My Foolish Heart’ and he had a wonderful small group that featured Sonny Stitt on baritone and tenor and Junior Mance on piano (2). Later in the decade he would record an album with John Coltrane, on alto, Jerome Richardson and Paul Quinichette, another album with Art Farmer, Jackie McLean and Duke Jordan and one with Idrees Sulieman, Pepper Adams and Mal Waldron (3). However, in 1958 he was convicted of possessing narcotics and was away from recording studios until 1960. Released on parole in June of that year he was soon recording for Prestige. On 16thJune in the company of Tommy Flanagan, piano, Doug Watkins, bass, Art Taylor, drums, and Ray Barretto, congas, Gene Ammons would produce what many critics regard as one the best albums of his career. ‘Boss Tenor’opens with a blues, ‘Hittin’ the Jug’. Two choruses from an unhurried Flanagan make way for Ammons to state the simple theme and then to stretch out, leaving plenty of space with just the occasional double-timed section to add excitement. This is masterful blues playing by someone who knows the value of taking his time. On Rodgers and Hart’s ‘My Romance’, a tune I usually associate with Ben Webster, Ammons shows that even when playing at half-power, he can produce a sound that is rich and enveloping. The tempo is at its fastest on Parker’s ‘Confirmation’, but Ammons is still unhurried, and the biggest hit of the session, ‘Canadian Sunset’, finds Ammons swinging mightily. After sharing front-line duties with the likes of Coltrane, Farmer and Adams, ‘Boss Tenor’ allows Ammons the opportunity to take centre-stage, and he doesn’t disappoint. The next day Ammons was back in the studio with organist Johnny ‘Hammond’ Smith, and produced another minor hit, ‘Angel Eyes’, though it would be a few years before that was released. But things would soon go wrong for the rising tenor star. As Ammons would later tell Leonard Feather , not long after the ‘Angel Eyes’ session, the authorities “said I had violated my parole and sent me back to the penitentiary. Luckily I didn’t have but five months left to complete the full sentence so I went back and did that and came home on a discharge in January of ’61.”

In the studios, the penitentiary, the studios

The next two years would be tremendously busy ones for Gene Ammons. Prestige, realising the appeal of Ammons to jazz and R and B fans as well as those who simply liked to hear ballads well played, made sure Ammons made frequent visits to the recording studios. The album ‘Nice and Cool’, with Richard Wyands, piano, Doug Watkins, bass, and J. C. Heard, drums, was recorded on 26th January, 1961, and the next day with the same rhythm section Ammons recorded the album ‘Jug’. ‘Boss Tenors’, featuring Ammons with Sonny Stitt, was recorded on 27th August and ‘Up Tight’, where some of the piano duties were in the capable hands of Patti Bown, was recorded in October 1961. The album ‘Twisting the Jug’, with Joe Newman, trumpet and Jack McDuff, organ, was recorded in November 1961 and ‘Brother Jack Meets the Boss’, which again had McDuff on organ, was recorded in January 1962. ‘Boss Tenors in Orbit’, recorded on 18th February, 1962, had Ammons with Sonny Stitt and organist, Don Patterson, ‘Soul Summit’, from 19th February, 1962, had Ammons alongside Stitt and McDuff on organ, while ‘The Soulful Moods of Gene Ammons’ from April 1962 has Ammons supported by a rhythm section of Patti Bown, piano, George Duvivier, bass, and Ed Shaugnessy, drums. On ‘Jug and Dodo’ from May 1962 Dodo Marmarosa is on piano and on ‘Bad! Bossa Nova’recorded in September 1962 the pianist is Hank Jones (4).

These productive times were brought to an end with a second conviction for possession of narcotics, though this time he was charged with intent to supply as well. According to Ammons, he could have faced “10 years to life” and when he “first went to court the judge did sentence…(him) from 15 to life”, though eventually his sentence was reduced to ten to twelve years and he served seven. He served his time at Stateville Penitentiary, Joliet, Illinois, where he had his horn, led a band of inmates, wrote for the band and did some teaching.

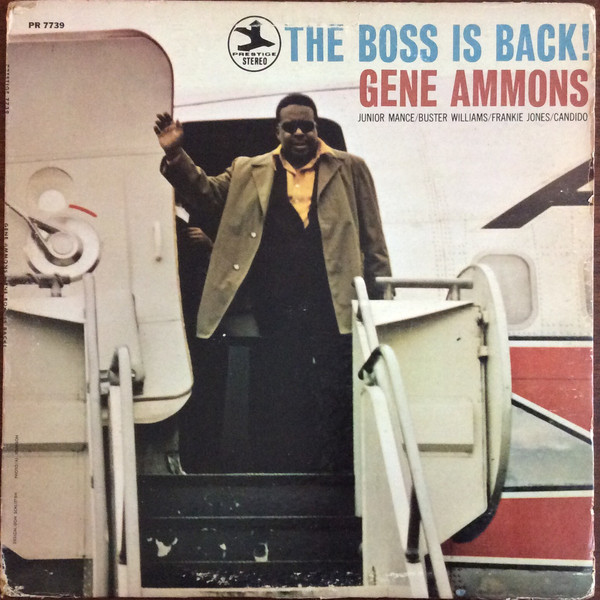

On 10th and 11th November, 1969, Ammons was back in Rudy Van Gelder’s studio in New Jersey. Two albums resulted from these sessions. ‘The Boss Is Back’ was released first and ‘Brother Jug’ released the following year. On ‘The Boss Is Back’ most of the accompaniment is provided by a conventional rhythm section that includes a pianist from early days, Junior Mance, plus the conga specialist, Candido. On ‘Brother Jug’ Ammons is supported by Sonny Phillips, organ, Billy Butler, guitar, Bob Bushnell, Fender bass, and Bernard Purdie, drums. Both albums show that Ammons is on top form. If anything his sound is bigger than ever with, perhaps, a shade more edge, and the ballad playing on ‘Here’s that Rainy Day’, ‘Didn’t We’ and ‘Blue Velvet’ is powerful and moving (5). Jug was definitely back.

His live performances were also something special, as Bob Porter has reported: “Ammons, the bandleader, was something to watch. He was a master at making his audience feel relaxed. A typical set might start with something very fast in order to get the players properly warmed up. He would then take the microphone and begin talking to the audience and introducing his sidemen. He might comment on something in the news or perhaps the weather, but all the time he was talking, his organist would be playing soft chords behind him that would gradually swell to the point that he’d introduce one of his hit ballads, and the club would go wild.”

In poor health

But Ammons was not in the best of health. Some accounts say that when he was released from Stateville Penitentiary, he was already suffering from emphysema, but the medical advice that he should stop smoking went unheeded. In late May 1974 he broke an arm in Oklahoma. He returned home to Chicago, where, according to Frederick J. Spencer, M.D., he was found to be suffering from cancer of the bone. A little later he contracted pneumonia. He died in Chicago’s Michael Reese Hospital on 6th August, 1974, aged forty-nine. His death certificate said that he died of lung cancer. This, Spencer suggests, was the cause of death and was likely to have been the cause of the secondary cancer and the subsequent weakening of the bones.

At Gene Ammons’ funeral service the Reverend Edsel Albert Ammons spoke in tribute to his brother, Dr. Louis Rawls, father of three-time Grammy winner, Lou Rawls, delivered the eulogy and Sonny Stitt played in tribute to his friend.

Gene Ammons sounded like a bruiser with a big warm heart, an in-your-face macho player with a sentimental side. He had the technique and the know-how of the boppers, but, in the main, he preferred a simpler more direct approach, which meant his music was always accessible, perhaps too accessible as far as some critics were concerned. (But, then, not many critics have swapped eights and fours with Sonny Stitt.) A leading instigator and exponent of what became known as soul jazz, his albums rarely disappointed. He could stir things up and holler and shout, and then change tempo to find the sweet spots of a ballad with an assured touch. And while he wasn’t always at liberty to record, when he had the opportunity, he recorded prolifically. As Richard Cook has written, “Like his father, Jug died young, although he left behind a voluminous legacy on record.” It is a legacy that is well worth listening to.

Peter Gardner

January, 2019

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to David Nathan, Jazz Archivist, The National Jazz Archive, Loughton Library, Traps Hill, Loughton, Essex. IG10 1HD, Steve Marshall, Marshall McGurk, Elm House Farm, Crosby, Maryport, Cumbria, CA 15 6SH and Dawkes’ woodwind specialist, Sam Gregory.

Endnotes

(1) ‘S. P. Blues’ is available on the CD ‘An Introduction to Albert Ammons: His Best Recordings, 1939-1947’, Best of Jazz, 4057.

(2) ‘Red Top’, ‘Idaho’, ‘My Foolish Heart’ and several recordings involving Gene Ammons with Sonny Stitt and Junior Mance are available on the four CD set ‘Gene Ammons, Quadromania, You Can Depend on Me’ Membran 222402-444.

(3) The album with Ammons and Coltrane, Richardson and Quinichette was called ‘Gene Ammons and His All Stars: Groove Blues’. The album with Ammons and Farmer and McLean was called ‘The Happy Blues: Gene Ammons’. The album with Ammons and Sulieman, Adams and Waldron was called ‘Blue Gene’. All three albums, but minus one track from ‘The Happy Blues’, plus the highly recommended album ‘Boss Tenor’ are available on the competitively priced ‘Gene Ammons, Three Classic Albums Plus’ Avid Jazz AMSC 1029.

(4) ‘Boss Tenor’plus the albums ‘Jug’, ‘Up Tight’, ‘Twisting the Jug’, ‘Brother Jack Meets the Boss’, ‘Soul Summit’, ‘Preachin’’ and ‘Bad! Bossa Nova’ are all available in ‘Gene Ammons: The Prestige Collection, 1960-1962’ EN4CD 9114, though this collection does not give personnel details.

(5) Both ‘The Boss Is Back’ and ‘Brother Jug’ have been issued on one CD: ‘Gene Ammons: The Boss Is Back’ Prestige PCD 24129-2.

Some sources used

Leonard Feather, ‘The Rebirth of Gene Ammons’, Down Beat,xxxvii, 12, 1970.

Leonard Feather and Ira Gitler, The Biographical Encyclopedia of Jazz(New York, Oxford University Press, 1999).

Bob Porter, Soul Jazz: Jazz in the Black Community, 1945-1975 (Xlibris, Milton Keynes, 2016).

David H, Rosenthal, Hard Bop: Jazz and Black Music, 1955-1965(Oxford University Press, New York, 1992).

Peter Silvester, A Left Hand Like God: A Study of Boogie-Woogie(Quartet Books, London, 1989).

Frederick J. Spencer, Jazz and Death: Medical Profiles of Jazz Greats (University Press of Mississippi, Jackson, 2002).

Dempsey J. Travis, An Autobiography of Black Jazz(Urban Research Institute, Chicago, 1983).