…and then came Phil and Lew

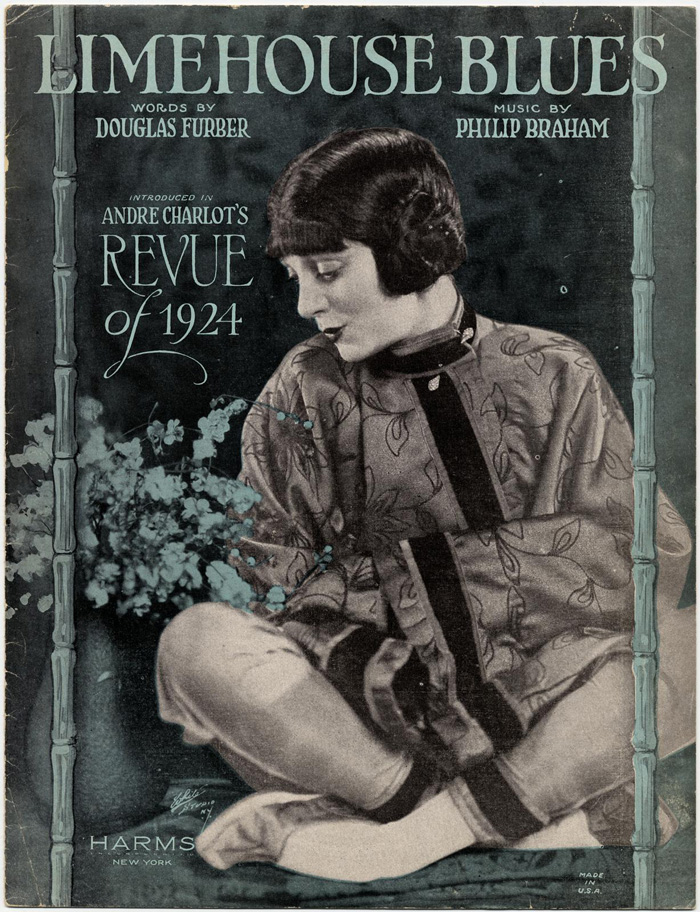

6th December 2019The musical revue, ‘A to Z’, opened on 11th October, 1921, at the Prince of Wales’ Theatre in London’s West End. It would run for 428 performances. Ivor Novello is credited as being the composer of ‘A to Z’, though other songwriters contributed pieces of their own, including the revue’s most durable song. Composed by Philip Braham with words by Douglas Furber, ‘Limehouse Blues’ would become something of a jazz standard or, if you have grown tired of musicians battling over its accommodating changes at breakneck speeds, maybe you would prefer the description ‘jazz warhorse’. Recorded by Paul Whiteman in the early 1920s and, several decades later, by the Sun Ra Arkestra, ‘Limehouse Blues’ certainly has staying power. It has also proved quite enticing to post-bop saxophonists wanting to give their awesome techniques a workout while providing their rhythm sections with a wake-up call. But more of them later.

A blues at the Prince of Wales

Despite its title, ‘Limehouse Blues’ isn’t a blues. Its refrain or chorus is not twelve, but thirty-two bars long, made-up of two sixteen bar sections. Written at a time when blues were starting to grow in popularity, its title would have added to the song’s appeal. Yet, what cannot be overlooked is that given the nature and sentiment of the lyrics, calling the song a blues may not be too wide of the mark. The Limehouse district of London, often seen by earlier generations as London’s Chinatown, is the setting for the song, and it speaks of a poor “Limehouse kid – Going the way that the rest of them did…nobody’s child…just kind o’wild”. As for the supposed singer of the song, he or she has learned “the real Limehouse blues – Learned from the Chinese those sad Chinese blues”. It’s a song of despair.

Surprisingly, few performances of ‘Limehouse Blues’ get anywhere near the sadness of the lyrics. The fact is that the repetition of notes at the start allows for the tune to be played quickly, even by those just learning their instruments, and, unlike another vehicle that seems built for speed, Ray Noble’s ‘Cherokee’, ‘Limehouse Blues’ doesn’t have a demanding bridge waiting to trap the young improvisor.

The copyright entry for the Library of Congress tells us that ‘Limehouse Blues’ was first published by Ascherberg, Hopwood and Crew in London in 1922 and that it was an instrumental piece. What then of the sad lyrics? According to Robert Rawlins in his book Tunes of the Twenties, the “words (for ‘Limehouse Blues’) were added for its appearance in the show Andre Charlot’s Review of 1924”, which opened on Broadway on 9thJanuary 1924, where Gertrude Lawrence’s delivery of the song stopped the show. She was on her way to becoming a star on both sides of the Atlantic.

But were Furber’s lyrics heard in ‘A to Z’ at the Prince of Wales’ Theatre? Sheridan Morley, Gertrude Lawrence’s biographer, insists that one of the revue’s highlights was ‘Limehouse Blues’ “by Philip Braham and Douglas Furber …(which) was set up as a duet for Gertie and (the established star) Jack Buchanan…” Morley even quotes part of the lyric, “In Limehouse, you can hear those blues all day’”. Lawrence’s own recollections of ‘A to Z’ bring another character into the story: “I heard Teddy Gerrard sing ‘Limehouse Blues’ for the first time; the orchestra was directed by Philip (Pa) Braham…” (‘Pa’ was Braham’s nickname.) As for ‘Teddy Gerrard’, I take this to be a reference to Teddie Gerard (1892-1942), an Argentine film actress and Broadway performer, who, according to the London Stage, joined the cast of ‘A to Z’ during its West End run.

So, I think we can say that ‘Limehouse Blues’, with words by Douglas Furber, was heard at the Prince of Wales a few years before it brought audiences to their feet on Broadway.

Early recordings

One of the earliest recordings of ‘Limehouse Blues’, without vocal refrain, was by Jack Hilton in 1922, and one of the first jazz recordings was by Red Nichols and His Five Pennies in May 1928 with Scrappy Lambert taking the vocal. Nichols, who treated his ‘Five’ with great elasticity, seems to have had twelve musicians plus Lambert in the studio for this session, including such talented instrumentalists as Miff Mole, trombone, Joe Venuti, violin, and Eddie Lang on guitar. Nichols played the song at a lively pace, though nothing like the cramp-inducing tempos that would soon become the norm.

Ellington’s version from 1931 also refrained from pushing the metronome to its limits. As one commentator put it, the Duke slowed ‘Limehouse Blues’ “down to a medium-tempo amble…which almost sounds like it could serve as a soundtrack for a cowboy movie given the horse-trot beat he employs.” Tricky Sam Nanton, trombone, Johnny Hodges, alto, Barney Bigard, clarinet, Harry Carney, baritone, all find solo space in Ellington’s arrangement before Cootie Williams, trumpet, brings things to a sombre close.

By 1934, however, pulses were starting to race. In February the Casa Loma Orchestra gave us an over-excited version of Braham’s song, with soloists struggling to keep up, and in September Fletcher Henderson and Orchestra recorded Benny Carter’s arrangement of the Limehouse song. The tempo again was up, but the soloing, especially from trumpeter Red Allen, was majestic, and the section work was tight. A few days later came the Mills’ Brothers version. This was bright with simulated trumpet playing and lots of scat singing, and when the words were sung, as with the Scrappy Lambert /Red Nichol’s version, the Brothers use the word ‘Chinkies’ rather than ‘Chinese’. Political correctness, like respect for minorities, was still a long way away.

For many people who are fans of this era, the definitive recording of ‘Limehouse Blues’ came a little later than the Mills’ Brothers’ version. It was recorded on 4th May 1936 by Django Reinhardt and Stephane Grappelli with the Quintette du Hot Club de France. The Quintette’s rather sedate first chorus seems to shield the listener from the tempo, but nothing is hidden in the second and subsequent choruses, with Django demonstrating his chordal ability on his long solo and Stephane still managing to bring a little delicacy to proceedings. If this set the benchmark, future rhythm sections would be earning their money.

Fleet-fingered Chu Berry with the fiery trumpet of Hot Lips Page gave us a speedy and spirited version of ‘Limehouse’ in 1937, and, as if to show he wasn’t too fatigued by the experience, Berry revisited the tune in 1939, this time in the company of Buster Bailey and trumpeter Wingy Manone. Sidney Bechet’s recording of ‘Limehouse’ from September 1941, as one might expect from a soloist who rarely took a backward step, was bold and forceful, but still allowed Charlie Shavers to show that he was one of the very few trumpeters who could hold his own with the New Orleans’ master. Art Tatum’s version from 1943 is an awesome display by a supreme musician that no doubt left some wondering how two pianists could play so seamlessly together, and Benny Goodman, with a sextet that included Lou McGarity on trombone and the teenage sensation, Mel Powell, on piano, recorded the piece twice in 1941, the second time with an extended two chorus solo, where Benny seems to take his time to build something of masterful delicacy.

Moving further into the 1940s, the Boppers, apparently, didn’t take to ‘Limehouse’. Maybe, like Parker, they preferred ‘Cherokee’s’ changes or something more complex when flexing their muscles. Yet plenty of those who followed Parker, the Post-Boppers as some have called them, have delighted in ‘Limehouse’s’ simple chordal demands.

Sonny, Cannonball, Trane, Phil and Lew

In August 1958 Sonny Rollins was the guest star with the Modern Jazz Quartet at the Music Inn, Lenox, Massachusetts. Listening to-day to part of their concert, we hear Rollins announcing that the next piece will be ‘Limehouse Blues’ and this is followed by a short discussion amongst the musicians (1). Suddenly drummer Connie Kay emerges, setting a fearsome pace on hi-hat. Percy Heath, bass, and Rollins soon join him. What follows is at times flippant, at times astonishing – Rollins’ command of the tenor saxophone is nothing less than astonishing – and frequently wonderfully inventive. Rollins’ tone is rich and sonorous, reminding me of an earlier generation when big sounds were the norm, and Heath and Kay provide effortless support, despite the tempo. This is very much jazz that doesn’t take itself too seriously played by masters. Three musicians at the peak of their powers having a bit of fun. For those of us struggling on the lower slopes, their amusement only stresses how far we have to go. A sad song from a 1920’s revue had acquired a huge smile.

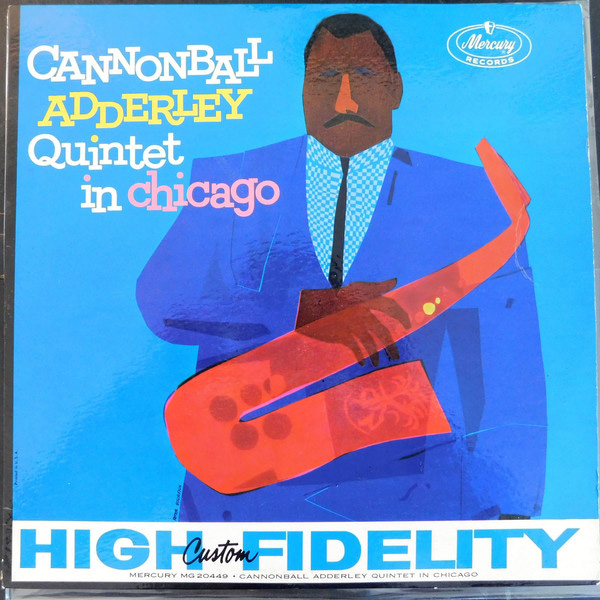

Less than a year later, in February 1959, five-sixths of the then current Miles Davis Sextet gathered in a recording studio in Chicago. The album they were about to make would be called ‘The Cannonball Adderley Quintet in Chicago’ and sharing frontline duties with the quick-silvered Adderley would be the musician who was soon about to transform tenor playing, John Coltrane (2). Precisely why two saxophonists at the forefront of jazz would choose to play a tune that had been doing the rounds for nearly forty years isn’t known. But they did and the result is superb.

After the opening chorus, where the two saxophonists play the ‘Limehouse’ melody, Adderley takes a two-chorus solo followed by two from Coltrane. The difference between the two soloists is quite stark; Adderley is dynamic and free-flowing, Coltrane more reflective and serious. If I were to award a prize, it would go to Adderley. Don Heckman in his original sleeve notes for the album disagrees: Coltrane “wins the laurels on this track…(for) a solo that bristles with an intense, driving propulsion.” (I always seem to hear better Adderley than most of the critics.) After a chorus from pianist Wynton Kelly, Adderley, Coltrane and drummer Jimmy Cobb have some exciting exchanges, before Cobb takes a back seat and leaves the soloing to the two horns. It’s all over in less than five minutes, which is no time at all given some of Coltrane’s later solos. Despite such brevity, this performance feels substantial, structured and complete. A wonderful addition to the ‘Limehouse’ legacy. But the best was still to come.

Phil Woods and Lew Tabackin are two musicians that probably only need one introduction, for Tabackin.

Lew Tabackin was born in Philadelphia in 1940 and his main instruments are tenor sax and flute. He has played with various groups and bands, and some of his best performances have been with the quartet and big band he formed with Japanese pianist, Toshiko Akiyoshi, whom he married in 1969. On tenor, while Tabackin has a softer side that reminds me a little of Paul Gonsalves, in the main he is a hard-driving, in-your-face kind of player. Just the person to give Phil Woods a fight.

It was on 10th December 1980 that Woods and Tabackin got together in New York’s Chelsea Sound Studio, with Phil on alto and Lew on tenor (3). The two reedmen start ‘Limehouse’ unaccompanied and at first you may be mistaken in thinking you have stumbled across a piece of free-form jazz, before the underlying chords impose their structure. After one chorus by the two horns, the rhythm section, of Jimmy Rowles, piano, Michael Moore, bass, and Bill Goodwin, drums, forces an entry, with Rowles in particular making his presence felt. Then there are solos, exchanges between the leaders, exchanges with drummer, more unaccompanied saxophones, the return of the rhythm section, a touch of the tune and a wild finish. This, say Richard Cook and Brian Morton, is “a ‘Limehouse Blues’ that takes the roof off”. All Music gave the album 4 ½ out of 5. (How did it lose 10%?) Has there ever been a better ‘Limehouse Blues’? I doubt it. If you have just one version in you collection, this is surely the one to have.

A modest success?

No one is going to argue that ‘Limehouse Blues’ belongs in the same category as ‘Stardust’ or ‘Body and Soul’. Perhaps ‘modest’ is the best way to describe the song. And, yet, this modest vehicle has stood the test of time, has proved attractive to some of the greatest of jazz musicians, especially saxophonists, and has led to some outstanding performances, performances that took off at speed and ended with huge smiles all round. That’s quite a success story for a modest song.

Peter Gardner

December, 2019

Acknowledgements

I am grateful for the help of Steve Marshall from Marshall McGurk, Maryport, Cumbria, and Sam Gregory, Dawkes’ woodwind specialist.

Endnotes

(1) This track can be found on the CD ‘Sonny Rollins and the Big Brass’, Verve 557 545-

(2) This album, including the track ‘Limehouse Blues’, was later released on the CD ‘Cannonball & Coltrane’, Emarcy 834 588-2.

(3) This session, including the track ‘Limehouse Blues’, was later released on the CD ‘Phil Woods/Lew Tabackin’, Evidence ECD 22209-2.

Some sources used

Richard Cook and Brian Morton, The Penguin Guide to Jazz on CD, Fifth Edition (Penguin, Harmondsworth, 2000).

Richard Cook and Brian Morton, The Penguin Guide to Jazz on CD, Fifth Edition (Penguin, Harmondsworth, 2000).

Ted Gioia, The Jazz Standards (Oxford University Press, New York, 2012).

Gertrude Lawrence, A Star Danced (W. H. Allen, London, 1945).

Sheridan Morley, Gertrude Lawrence (Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London,1981).

Robert Rawlins, Tunes of the Twenties (Rookwood House Publishing, Clayton, NJ, 2015).