‘Ronnie Peters’, ‘Buckshot La Funke’, Julian ‘Cannonball’…

8th September 2017Join jazz aficionado Peter Gardner with his look back at the one and only Julian ‘Cannonball’ Adderley…

Some accounts of his arrival on the New York jazz scene read like an exaggerated piece of jazz folklore. Aged twenty-six, already a successful high school music teacher, he was in New York with a view to starting graduate studies to add to his already impressive educational CV. On Saturday 19th June, 1955, he had his alto with him and rather than leave it in a car, which could be fraught with danger in New York, he took it with him into Café Bohemia to hear a group led by bassist Oscar Pettiford. Pettiford’s tenor player, Jerome Richardson, hadn’t shown up and neither had his dep.

Desperate to find a tenor player, Pettiford spotted Charlie Rouse in the audience, but Rouse, who would find fame with the Thelonius Monk Quartet, didn’t have his horn with him. Pettiford then tried to get Rouse to borrow the alto from the portly young man with the alto case in the hope that Rouse would be able to transpose the tenor parts. But, instead of asking if he could borrow his alto, Rouse asked the visitor to New York if would like to play with the Pettiford group.

The young man accepted the invitation and, despite Pettiford’s best efforts to catch him out with extreme tempos and pieces with difficult changes, he played brilliantly. Somewhere in the Bohemia’s audience sat Phil Woods and Jackie McLean. On realising that the competition in New York for jazz alto players had just gone up several notches, they turned to one another and, in unison, uttered the same expletive.

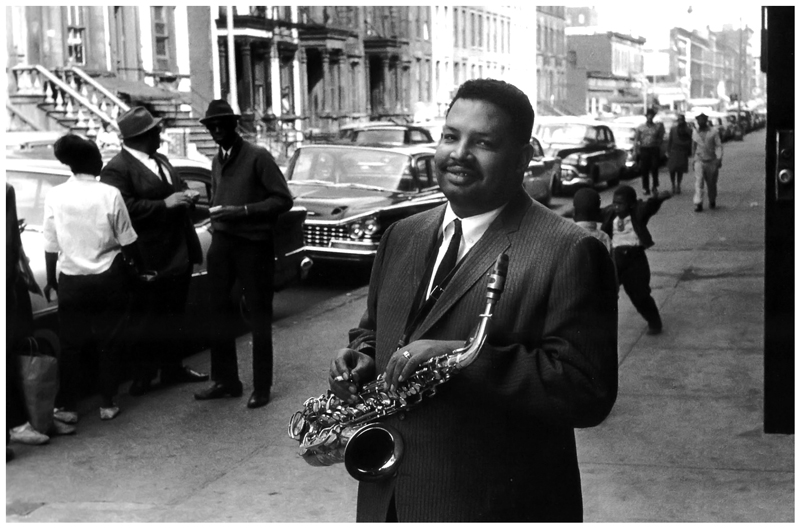

Julian ‘Cannonball’ Adderley

Cannonball had arrived and, as his biographer, Cary Ginell, would later write, “News about Cannonball Adderley’s debut at Café Bohemia spread like wild fire. All people could talk about was the alto man who called himself Cannonball and played like Charlie Parker.” Before the end of July 1955 the same alto man had appeared at Café Bohemia on at least another twenty-four occasions, had signed a record deal with EmArcy and had made four visits to the recording studios.

Julian Edwin Adderley Jr. was born on 15th September, 1928, in Tampa, Florida, but would soon move to Tallahassee, where his parents taught at the Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University. Both Julian’s uncle and father were heavily involved with band music, and one of Julian’s early musical experiences was hearing the great Fletcher Henderson Orchestra. Coleman Hawkins, Henderson’s star tenor player, became one of Julian’s first musical heroes, but when the time came for the youngster to take up a saxophone, he had to make do with an alto, not a tenor.

Coleman Hawkins

As for the nick-name ‘Cannonball’, he had originally been dubbed ‘Cannibal’ because of his voracious appetite, but over the years this had become ‘Cannonball’, a name that came to fit a man of very ample proportions and a saxophonist of frightening speed who could blast the opposition away. But at times when he started out trying to make a living as a jazz musician and was under contract to EmArcy, he did some moonlighting with other record companies and changed his name completely. ‘Cannonball’ became the mundane ‘Ronnie Peters’ on Milt Jackson’s album, ‘Plenty, Plenty Soul’(1), though in his Down Beat review of the album Ralph Gleason insisted that “The wonderfully earthy altoist…must be Cannonball Adderley”, and Cannonball used the more exotic ‘Buckshot La Funke’ on Louis Smith’s album, ‘Here Comes Louis Smith’ (2), only for Leonard Feather to give the game away in his liner notes claiming that “Buckshot La Funke (of the Florida La Funkes) is one of the modern alto giants and has been described by Nat Adderley as ‘my favourite soloist and main influence’.”

No doubt EmArcy was peeved at such extra-curricular activities, though, in truth, EmArcy had not gone out of its way to promote Cannonball or the quintet, preferring, or so it seemed, not to release some of his recordings until the alto player and his group had found favour amongst the record-buying public by their own or other people’s efforts.

And Cannonball had tried hard. A few months after his success at the Café Bohemia, he had quit his high school job and formed a quintet with Nat, his cornet-playing brother, in order to pursue a career as a professional jazz musician. Initially the quintet had found regular work and was critically acclaimed, but by the summer of 1957 the group’s debts were mounting steadily, good gigs were becoming harder to find and fame, buoyant record sales and financial security seemed distant dreams. Things changed dramatically for Cannonball in the autumn of the year. He disbanded his own quintet and joined Miles Davis, and at the start of 1958 John Coltrane joined the Davis group helping form a sextet with one of the most famous frontlines in the history of jazz: Miles Davis, trumpet, John Coltrane, tenor, and Cannonball Adderley, alto.

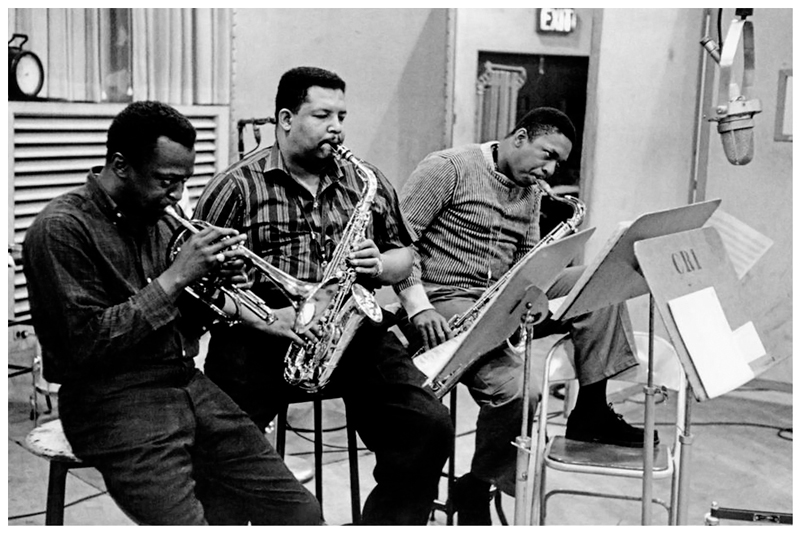

Miles Davis, Cannonball Adderley & John Coltrane

The sextet’s album ‘Milestones’, recorded on 4th February and 4th March, 1958, was, perhaps, a sign of things to come. The album ‘Kind of Blue’ was recorded by the Davis group on 2nd March and 22nd April, 1959, and while some would see this album as instigating a modal revolution, it sounds not so much revolutionary as wonderfully poised and assured. It would become, as Richard Cook has pointed out, “the stuff of legend…the most admired and feted jazz record of the LP era” and by the start of the 21st Century CD and LP sales of ‘Kind of Blue’ would run into the millions.

However, in the late 1950s, despite Davis’ group being both an artistic and financial success and despite Adderley making several recordings under his own name while a member of the famous sextet (3), Davis’ star alto player was keen to go back to leading his own band. He would eventually do so in September 1959 when the Cannonball Adderley Quintet, with brother Nat on cornet, Bobby Timmons, piano, Sam Jones, bass, and Louis Hayes, drums, opened in Philadelphia.

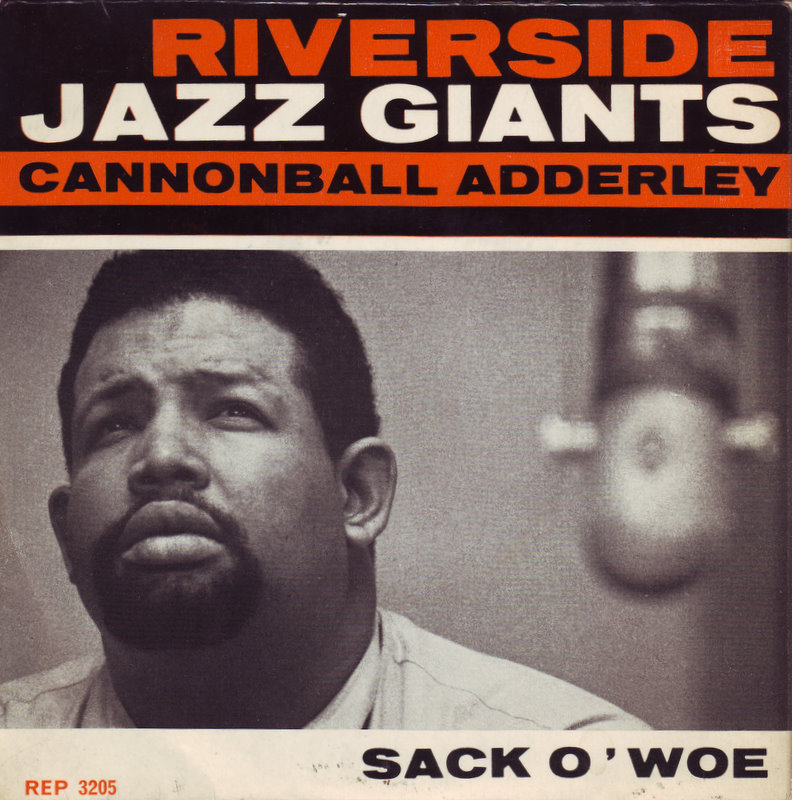

Soon, with recordings such as ‘Dis Here’, ‘Spontaneous Combustion’, ‘Work Song’, ‘Sack O’ Woe’ and ‘African Waltz’ (where Cannonball fronted a big band) proving immensely popular, with ‘gospel’, ‘funk’ and ‘soul’ being used to describe and help attract a mass audience to the quintet’s music, and with sold-out club appearances and guest spots on television shows, the Cannonball Adderley Quintet became one of the most marketable jazz groups in the world (4). Since many people have never been able to reconcile jazz with popularity, Cannonball and his music attracted criticism from several quarters.

As early as 1960 Charles Mingus dismissed Cannonball as “a rock ‘n’ roll musician, No. 1” and some writers decried the group’s funk as being over-done, fake and contrived. Nat observed at the time, “Man, we’re really getting it from all sides”, but he was quick to defend his brother’s music: “if Cannonball is going to be put down because he has managed, in some measure, to communicate with a larger audience, then I feel that those who would condemn him are hypocrites. We all fight each day for jazz acceptance. Why must we condemn those who gain it?”

‘Sack O’Woe’ – Cannonball Adderley

Criticism, whether from hypocrites or not, had little effect on the quintet’s continued success and neither did changing pianists or adding musical variety. When the group toured Europe in 1960 and 1961, Britain’s Victor Feldman was at the piano, sometimes doubling on vibes, and bassist, Sam Jones, would take the occasional solo on cello. Feldman left the group in the spring of 1961 and Cannonball didn’t find a long-stay replacement for a couple of months, but when he did, he struck gold. Viennese-born and conservatory-trained Joe Zawinul joined the Adderley quintet in June 1961, soon to be followed by a tenor saxophonist, who also played flute and oboe, Yusef Lateef. When Lateef departed at the start of 1964, he was replaced by Charles Lloyd, a young tenor saxophonist and flautist who embraced the innovations of Ornette Coleman and John Coltrane. But when Lloyd left in the summer of 1965, the Adderley brothers didn’t seek a replacement; their basic working group would remain a quintet for the rest of their time together.

As for Zawinul, he stayed for over nine years and composed the quintet’s most popular number, which was recorded in 1966, ‘Mercy, Mercy, Mercy’. According to discographer Chris Sheridan, “At a time when the Beatles and their acolytes were holding the heights of popular attention…’Mercy, Mercy, Mercy’ (became) one of the few jazz records to make the listings as a Top Ten pop single…within six months, the single had posted sales of a massive 750, 000”. Zawinul left Adderley in 1970 to join Wayne Shorter and form Weather Report, another group that had tremendous appeal

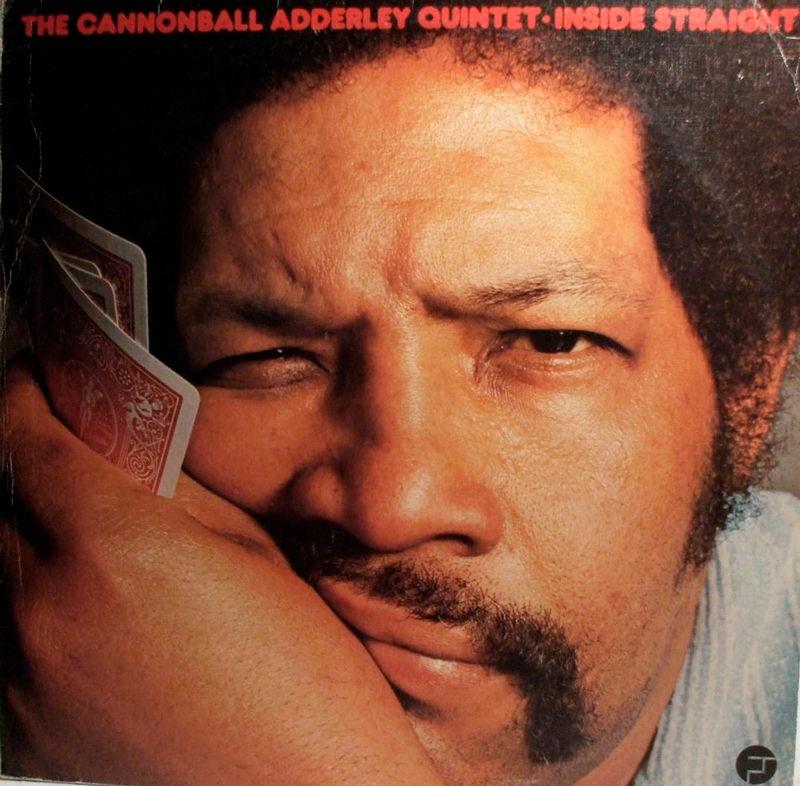

Capitol, the record company Cannonball had signed for in 1964, must have been delighted with the success of some of Adderley’s recordings, but what Sheridan has described as the “commercial pressures” of working for such a big record company and what brother Nat saw as the pressure to “make records for the charts” eventually resulted in the quintet leaving Capitol and moving to Fantasy Records and the jazz-friendlier production values of Orrin Keepnews. The group’s first album for its new label in 1973 was ‘Inside Straight’, an attempt, or so it has been suggested, for the quintet to turn the clock back.

‘Inside Straight’ – Cannonball Adderley

Sadly Cannonball’s association with Fantasy was not long-lived. In July 1975, after a workshop and concert at a high school in Milwaukee, one of numerous educational events that were part of the quintet’s schedule resulting from the leader’s deep commitment to jazz education, Cannonball and Nat stayed at a motel in Gary, Indiana. While there Cannonball, who had suffered from diabetes for most of his adult life, had a stroke and went into a coma. He died in St. Mary Mercy Hospital, Gary, Indiana, on 8th August, 1975. He was forty-six years old. He had been a professional jazz musician for nearly twenty of those years.

There was a time in the 1950s, at the start of Adderley’s professional jazz career, when the alto saxophone was in danger of becoming the delicate member of the jazz family. Parker’s drive and excitement were being replaced by sounds that were restrained, refined, cool and scholarly. Cannonball served as an inspiring antidote to such tendencies, and later, when the fads for fusion and electronics were exerting their commercial weight, Cannonball showed he could soar above such fashionable musical settings. Yet, no matter how sophisticated his harmonic explorations or how technically miraculous his flights of fancy, there was, to borrow Gleason’s idea, a wonderful earthiness in Adderley’s playing. On up-tempo pieces, there was fire and passion, and his ballad performances were invariably infused with the blues; his vocabulary was rooted in jazz’s vernacular. He was an outstanding jazz musician and, though it sparked resentment, an immensely popular one.

Peter Gardner

August, 2017

Acknowledgements

I am most grateful for the help of Steve Marshall from Marshall McGurk, Maryport, Cumbria, David Nathan, Jazz Archivist, National Jazz Archive, Loughton Central Library, Trapps Hill, Loughton, Essex, IG10 1HD, and Sam Gregory, Dawkes’ woodwind specialist.

Endnotes

(1) Milt Jackson’s ‘Plenty, Plenty Soul’ has been issued on the double CD: Milt Jackson, ‘Four Classic Albums Plus’, Avid Jazz, AMSC 979.

(2) This album would later be released as the CD: Louis Smith, ‘Here Comes Louis Smith’, Blue Note, 50999 5 14381 28.

(3) One memorable Blue Note session in March 1958 with Adderley as leader featured Miles Davis as a sideman! The resulting album, Julian ‘Cannonball’ Adderley, ‘Somethin’ Else’, has since been issued on the CD Blue Note 0777 7 4638 2 6. Another memorable album from this period with Adderley as leader features a quintet with Coltrane on tenor and the rhythm section from the Davis sextet. Originally issued on the Mercury label as ‘Cannonball Adderley Quintet in Chicago’, this has since been reissued on CD under the same title on Verve 559 770-2 and as ‘Cannonball & Coltrane’ on Emarcy 834 588-2. Although recorded in February 1959, the Adderley/Coltrane album was not issued until the Autumn of 1960, by which time Cannonball had found fame away from Davis’ sextet.

(4) Thirty-two Adderley albums, including ‘Somethin’ Else’ and ‘Cannonball Quintet in Chicago’, are available in a competitively priced three boxed set collection, with four CDs per set: ‘Cannonball Adderley, The Complete Albums Collection, 1955-1958’, Enlightenment EN4CD9082; ‘Cannonball Adderley, The Complete Albums Collection, 1958-1960’, Enlightenment EN4CD9083; and ‘Cannonball Adderley, The Complete Albums Collection, 1960-1962’, Enlightenment EN4CD9084. Unfortunately this collection does not give personnel details.

Some sources used

Adderley, N., ‘Nat talks back’, Down Beat, 4th August, 1960.

Cook, R., It’s About That Time: Miles Davis On and Off Record (Atlantic Books, London, 2005).

Ginell, C., Walk Tall: The Music and Life of Julian “Cannonball” Adderley (Hal Leonard, Milwaukee, 2013).

Gitler, I., ‘Mingus speaks – and bluntly’, Down Beat, 21st July, 1960.

Sheridan, C., Dis Here: A Bio-Discography of Julian “Cannonball” Adderley (Greenwood Press, Westport, 2000).