‘Summits and Beyond’

13th August 2019Peter Gardner

Accounts of when Soprano Summit’s musicians first got together all mention that it was at the end of one of the Dick and Maddie Gibsons’ annual jazz parties. It was early September 1972 and the party, which was held at the Broadmoor Hotel in Colorado Springs, had nearly run its course. For the last few days the Broadmoor’s guests had heard some wonderful musicians. Amongst the trumpeters who had taken to the stage were Ruby Braff, Clark Terry and Joe Wilder. Buster Cooper, Urbie Green and Frank Rosolino were some of the trombonists who had entertained the party crowd and saxophone masters Budd Johnson, James Moody and Flip Phillips along with legendary pianists Hank Jones and Teddy Wilson had all played their parts.

The closing night’s audience had heard all manner of all-star combinations over the weekend, and just as fatigue and satiation threatened, someone suggested an unusual frontline of two soprano saxophones. Bob Wilber and Kenny Davern took to the stage. The first-class rhythm section, with Dick Hyman, piano, Bucky Pizzarelli, guitar, Milt Hinton, bass, and Bobby Rosengarden, drums, was ready. Ellington’s ‘The Mooche’ was proposed and agreed upon. They were off. According to Bob Wilber, “When we hit the last minor chord of the piece, playing in thirds at the top of our horns, the audience rose to its feet and burst into tumultuous applause.” Another account tells of ‘The Mooche’ provoking “intense excitement and a long, standing ovation”. Davern was said to be in tears. “A new sound had been born and it was the beginning of Soprano Summit” was Wilber’s summary of what had happened.

Twenty-nine years later, Wilber and Davern would still be leading their small jazz ensembles, still upholding their musical values and thrilling audiences with their tight arrangements and expansive and eloquent solos.

Different sides of the track

Bob Wilber’s early life was one of comfort and privilege. He was born on 15thMarch 1928 into a respected upper-middle-class family. Bob’s father, Allen Sage Wilber, a university graduate, was partner in a well-established printing firm that specialised in academic publications. Bob’s mother died when he was young, and his father remarried. His stepmother, in contrast to those one reads about in tales of blighted childhoods, was a kind and, in his Bob’s own words, “gracious lady”. His father’s record collection seems to have played a crucial role in introducing Bob to jazz and his parents also took him to hear the stars of the times, including the Teddy Wilson Sextet at Café Society Uptown and the great Duke Ellington Orchestra at Carnegie Hall.

Yale or Princeton and a career in law or medicine figured in the plans his parents had sketched out for their son, but Bob’s energies were devoted to the clarinet and the musical fortunes of The Wildcats, a Dixieland band some of whose members, including pianist Dick Wellstood, had played with Bob in his high school days. In 1946 Bob Wilber started to have lessons with the great Sidney Bechet, eventually moving into Sidney’s house. Despite Bob’s life going in a very different direction to the one they may have hoped for. Wilber’s parents did not stand in his way and even paid the rent when their son was Bechet’s lodger. In later life, a sum of money bequeathed to him by one of his grandmothers meant that Wilber was free to devote his energies to the music he loved.

Kenny Davern was seven years younger than Wilber, and details of Kenny’s early days read like the preface to a life in crime or boxing or both. According to Davern’s biographer, Edward Meyer, Kenny’s maternal grandfather, John Joseph Davern, emigrated from Ireland, married in America and lived in the New York area. John Joseph worked for a telephone company and, after falling from a telephone pole, began to suffer fits of aggression. One day in April 1925 he shot and killed his wife. Fortunately, his children were not at home. Next day he was committed to a hospital for the insane. One of John Joseph’s sons, who would acquire the name ‘Buster’, was Kenny Davern’s father.

Kenny’s maternal grandparents were Orthodox Jews. His maternal grandfather, who was an officer in the Austro-Hungarian army, emigrated to America and married a Russian immigrant. The couple had a daughter, Josephine. Despite parental disapproval and warnings, Josephine was attracted to Buster Davern and eventually Josephine and Buster eloped. In 1934 Buster was sentenced to New York’s maximum-security prison, Sing Sing, for his part in an armed robbery in which a policeman was shot and killed and a night watchman was wounded. At the time Buster was sentenced, Josephine discovered she was pregnant. John Kenneth Davern was born on 7thJanuary 1935. Several of Kenny’s early years were spent in the harsh life of boarding schools, some run by nuns, and foster homes. Eventually Kenny and his mother moved in with his Orthodox Jewish grandparents, who spoke Yiddish and who had their own views about how Kenny should be brought up.

Working life before Soprano Summit

Bob Wilber recorded with The Wildcats and with Sidney Bechet, he appeared at the Nice Jazz Festival in 1948, and was a sideman with Eddie Condon’s Band during its British Tour in 1957. Wilber also recorded with Condon, with Wild Bill Davison, with Benny Goodman, with Jack Teagarden and Bobby Hackett, with his own small groups and was a member of the World’s Greatest Jazz Band. From the time he started his career in the 1940s, Bob Wilber was a respected musician in traditional and mainstream jazz circles. For a while, to avoid being thought of as a Bechet clone, Wilber gave up the soprano saxophone, but in the 1960s he began playing a curved soprano and his own identity as a soprano saxophonist began to emerge. Later in life Wilber also reacquainted himself with the alto saxophone and his love of Johnny Hodges.

In 1953 an eighteen-year-old Kenny Davern was trying life on the road. He was playing baritone and alto, and, like many before him, he found that being part of a big band was neither musically nor financially rewarding. Playing clarinet in small-group jazz settings would find Davern at his happiest. Inspired by Pee Wee Russell and by classical clarinettists Leon Russianoff and David Weber, for Davern tone and expressiveness were paramount. He honed his skills as a clarinettist in the bands of Jack Teagarden, Pee Wee Erwin, Phil Napoleon and the Dukes of Dixieland. As for the soprano, it is claimed that he took it up when the small group he was leading needed a stronger voice than Davern’s clarinet but couldn’t afford a trumpeter. His insistence that if there was one thing worse than a soprano, it was two of them, doesn’t seem to have stopped him from becoming an excellent soprano player or an excellent duettist with Wilber.

Soprano Summit’s early days

It wasn’t until December 1973, fifteen months after the success of the Gibsons’ jazz party, that Soprano Summit were able to assemble in a recording studio and record an album under their own name. (Eventually issued on ‘Soprano Summit’, World Jazz WJCD -5/13.) But the results were extraordinary. ‘Swing Parade’, a piece by Sidney Bechet that he first recorded in the 1940s, explodes with pace and assurance as the two sopranos and Hyman’s stride accompaniment produce something that far outstrips its parts. On Bechet’s ‘Egyptian Fantasy’ Wilber and Davern stick to their clarinets with richness and gentility. Both of these clarinet masters seem to belong to a tradition that precedes the cooler precision of Goodman and his followers, where embracing the listener with sounds that are warm, ripe and richly satisfying is the primary objective.

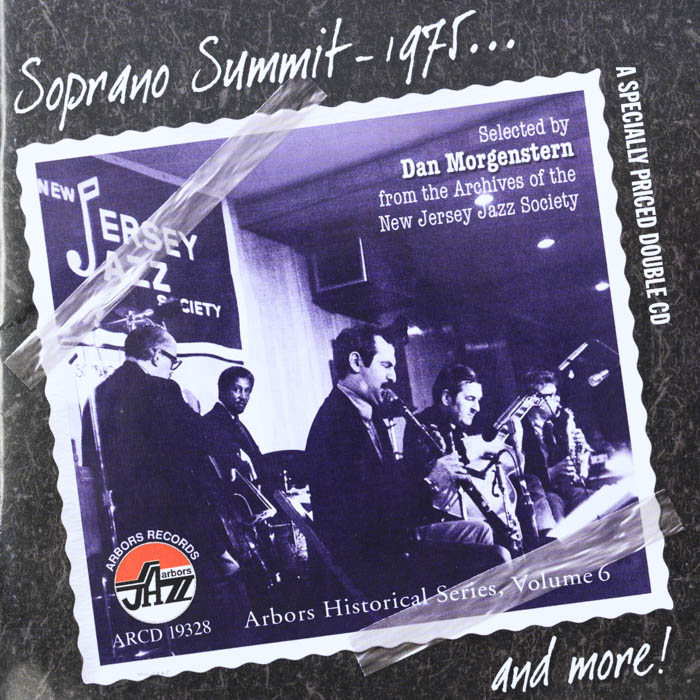

Later recordings by Soprano Summit show some changes in personnel. At a concert for the New Jersey Jazz Society in April 1975, the line-up is Davern, Wilber, Marty Grosz, guitar, George Duvivier, bass, and, Connie Kay, drums (Eventually issued on ‘The Soprano Summit in 1975 and More’, Arbors ARCD 19328.) After years as a professional musician, Marty Grosz, guitarist, banjoist, vocalist and raconteur, seems to have been driven by poverty into contemplating a career outside music. A phone call from Wilber brought him back into the fold. Soprano Summit was finding that venues with reliable pianos were more and more difficult to come by; Grosz’s all-round talents would make him an excellent member of a group with just a three-piece rhythm section. Bassist George Duvivier was another of the excellent replacements who played their spells with the two reedmen, and Connie Kay, of one of the MJQ’s stalwarts, would have been a wonderfully reliable drummer no matter how brief his stay with Summit’s leaders.

One tune recorded on that evening in April 1975 had become one of the group’s most-requested pieces. ‘Song of Songs’, a favourite of Bechet’s and amongst drunks and aspiring tenors, could be layered with so much sentimentality as to defy digestion. The version by Wilber and Davern is sparse and restrained until its final notes. It is easy to appreciate why the Summit’s version of this song was reserved for what Marty Grosz calls “that exalted spot on the program known as ‘next to closing’.”

In the spring of 1976 Soprano Summit were back in the recording studios with Grosz on guitar and banjo, Duvivier on bass and Fred Stoll taking over drumming duties. ‘Nagasaki’, ‘Black and Tan Fantasy’, ‘Everybody Loves My Baby’ and ‘Ole Miss’ are some of the lively, traditional fare from this outstanding session together with three Wilber originals. (Issued on ‘Soprano Summit’, Chiaroscuro CR(D) 148.) A few weeks later Soprano Summit featuring Wilber, Davern and Grosz but with Ray Brown, bass, and Jake Hanna on drums gave a thrilling performance that was recorded. ‘Stompy Jones’, ‘Swing that Music’ and a Wilber original dedicated to Billy Strayhorn, ‘The Golden Rooster’ are some of the gems that Concord issued on their CD ‘Soprano Summit in Concert’ (CCD-4029).

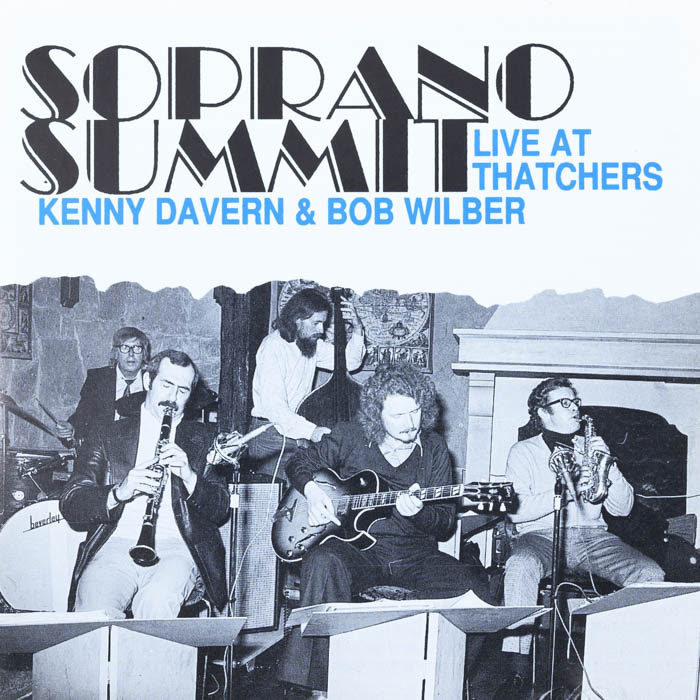

A few months after their ‘…in Concert’ recording, during a British tour, Wilber and Davern were recorded at Thatcher’s Hotel, East Horsley, Surrey. Eventually released in 1992, ‘Soprano Summit at Thatchers’ was voted second best New Issue of ’92, with 92 points in Jazz Journal’s Critics’ Choice, where it was only bettered by Stan Getz’s Spring is Here, with 95 points. (‘Soprano Summit at Thatchers’ was issued on J&M Recordings, J&MCD 501.) A British rhythm section of Dave Cliff, guitar, Peter Ind, bass, and Lennie Hastings, drums, accompanied Wilber and Davern on their ‘Thatchers’ CD, and the results are excellent, with the two leaders on exceptional form. Favourites like ‘Meet Me Tonight in Dreamland’, ‘Ol’ Miss’ and ‘Oh Sister Ain’t that Hot’ provide the excitement, though some of the most intense moments come from Wilber and Davern on clarinets playing ‘Old Stack O’ Lee Blues’ in a dedication to the New Orleans veteran Albert Burbank who had recently died. In his review of the CD Eddie Cook says that this track contains Wilber’s finest soloing. Alun Morgan, in his sleeve note, says that Davern’s solo that follows Wilber’s “must be one of the finest blues solos on record”.

In September 1977 with Grosz, Duvivier and Bobby Rosengarden back on drums, Soprano Summit recorded the album ‘Crazy Rhythm’ for the Chiaroscuro label. (Wilber played carinet, soprano and alto, while Davern played clarinet, soprano and C-melody saxophone, and this recording is available on Sprano Summit, CR(D) 148.) The tunes selected look perfect for a Soprano Summit album: Hawkin’s ‘Netcha’s Dream’, ‘When Day Is Done’, ‘When My Dreamboat Comes Home’, ‘There’ll Be Some Changes Made’ and ‘If You Were the Only Girl in the World’ are wonderful vehicles for clarinet and soprano duets and exchanges, but to my ear at least, the extra instruments played by the leaders, fail to provide the lift of earlier Summits. More variety has led to less spice.

Soprano Summit was formally dissolved in May 1978. It had lasted for just a few memorable years and various reasons have been given for its passing: its leaders had different personalities – Wilber was studied and calm while Davern was feisty and impulsive; when the fees of its three or four rhythm players were deducted from the group’s earnings, there was little left for the leaders; there were too few engagements in any case; Davern disliked having to repeat tunes and arrangements that audiences expected; selecting numbers and writing arrangements meant that Wilbur had the far heavier workload without any particular benefit; both leaders had other irons in the fire and had things they wanted to do.

…and then Summit Reunions

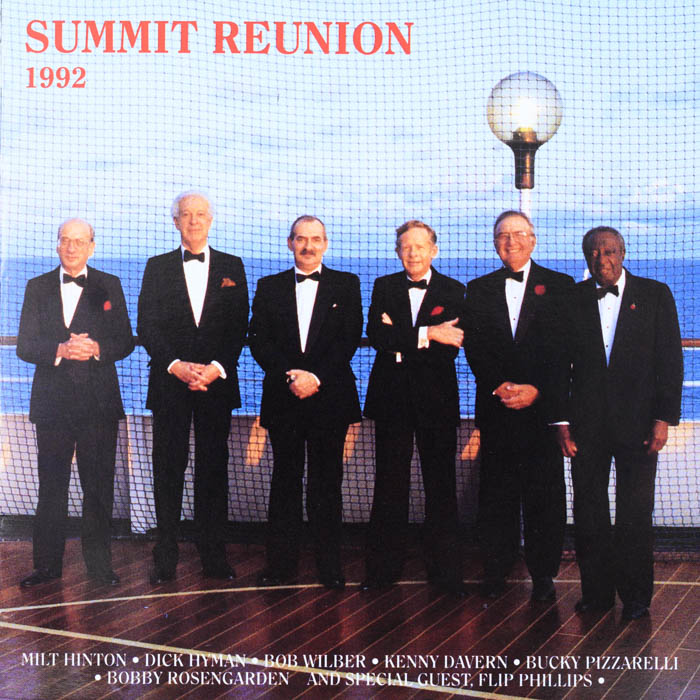

Whatever the precise reasons for the break-up of Soprano Summit, they did not prevent Wilber and Davern getting together later in their careers to lead groups known as Summit Reunions. In May 1990 the exact same personnel that first appeared at the Gibsons’ jazz party in 1972, but with Davern now restricting himself to clarinet, got together in Rudy Van Gelder’s New Jersey Studio with new arrangements but with the old verve. (Available as ‘Summit Reunion’, Chiaroscuro, CR(D) 311.) The same group reassembled aboard the S.S. Norway in October 1992 to record the album ‘Summit Reunion 1992’ ( CR(D) 324.)and met up again in Van Gelder’s Studio in March 1995 to record ‘Summit Reunion: Yellow Dog Blues’ (CR(D) 339), an album which, in addition to Handy’s ‘Yellow Dog’, contains a very spirited version of ‘Hindustan’, where all of the rhythm section, including eight-four year-old Milt Hinton, excel.

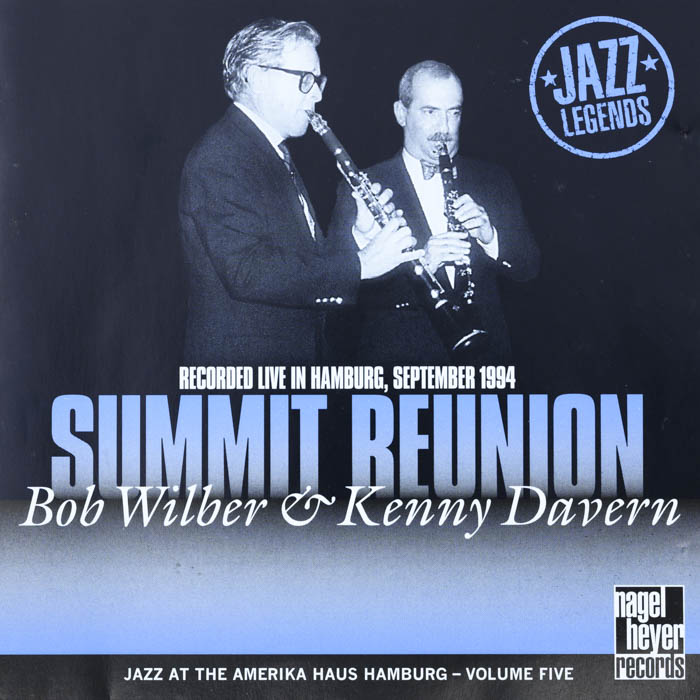

And the leaders kept going. In September 1994, with a wonderful British rhythm section of Dave Cliff, guitar, who played on the famous recording at Thatchers in 1976, Dave Green, bass, and Bobby Worth, drums, Summit Reunion gave a memorable concert in Hamburg (‘Summit Reunion, Recorded Live in Hamburg’, Nagel-Heyer CD 015). ‘Reunion at Arbors’ in March 1997 has Buck Pizzarelli back on guitar (Arbors, ARCD- 19183), ‘Traveling’, recorded in Sori and San Marino in July 1998 has Wilber and Davern fronting an Italian rhythm section (Musica Jazz, MJCD -1126), ‘You Ain’t Heard Nothin’ Yet’, a studio session from April 1999, has Summit Reunion playing Al Jolson songs (Jazzology, JCD-328) and ‘Summit Reunion in Atlanta’ recorded in April 2001 features a collection of 1920’s favourites (Jazzology, JCD-385).

Formed to provide a little novelty to jaded partygoers, the duet of Davern and Wilber has passed the test of time. The two reedmen brought vitality, enthusiasm and integrity to a tradition and repertoire whose best years many thought were over. Wonderful players individually, Davern and Wilber sparked each other to great things and, fortunately, many of their greatest achievements have been captured on record.

Kenny Davern died in December 2006 at his home in Sandia Park, New Mexico. As I was finishing this piece, I heard that Bob Wilber had passed away, aged ninety-one, at his home in Chipping Campden, Gloucestershire, England. It is doubtful if there will ever be another with his contacts, his experiences, his ability and his commitment. An extraordinary life and a dedicated one.

Peter Gardner

August, 2019

Acknowledgments

I am most grateful to Steve Marshall from Marshall McGurk, Maryport, Cumbria and to Dawkes’ woodwind specialist, Sam Gregory

Some sources used

John Chilton, Sidney Bechet: The Wizard of Jazz (Macmillan, Basingstoke, 1987).

Eddie Cook, ‘Soprano Summit at Thatchers’, Jazz Journal International, Vol. 45, No. 11, Nov. 1992, p. 46.

Edward N. Meyer, The Life and Music of Kenny Davern (The Scarecrow Press, Lanham, Maryland, 2010).

Edward N. Meyer, Giant Strides: The Legacy of Dick Wellstood (The Scarecrow Press. Lanham, Maryland, 1999).

Bob Wilber, Music Was Not Enough (Bayou Press, Oxford, 1987).