The Duke, Hawk and maybe Lorenzo

23rd March 2018According to John Chilton, despite all the musicians who met up at the recording studio on that August afternoon being “hard bitten veterans who had made thousands of records between them”, nevertheless the occasion “seemed special”. This was going to be no ordinary recording session; it would involve two musical legends who, or so they insisted, had been intending to get together for decades. But record producer Bob Thiele had finally made it happen. The date was 18th August, 1962.

The venue was the Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey. The musical legends were Duke Ellington, band leader since the 1920s, arranger and pianist, who nowadays is frequently seen as one of the twentieth century’s greatest composers, and Coleman Hawkins, a tenor saxophonist with such a long and distinguished career that he was often said to have invented his chosen instrument.

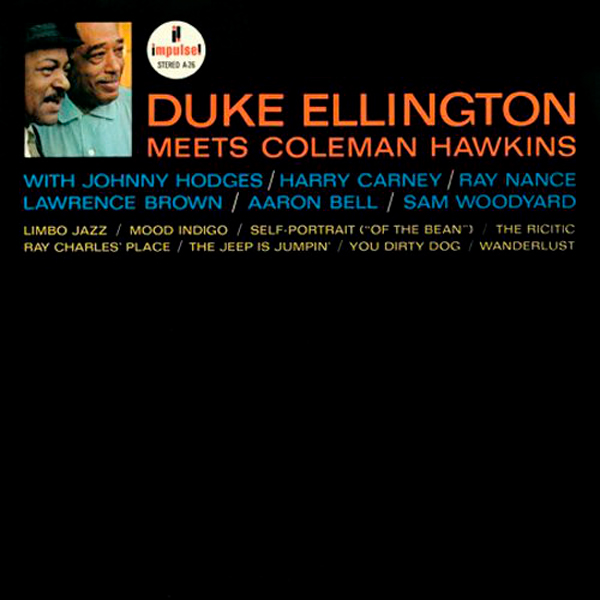

To accompany Hawkins Ellington had assembled a star-studied small group of veterans drawn from his distinguished orchestra. Sam Woodyard was on drums, Aaron Bell was on bass, and the frontline could hardly have been bettered: Johnny Hodges, alto sax, Harry Carney, baritone sax and bass clarinet, Lawrence Brown, trombone, and Ray Nance, cornet and violin – a quartet of musicians who between them had been with the Duke for about one hundred years. The resulting album would be called ‘Duke Ellington meets Coleman Hawkins’ (1).

‘Bean’, one of Hawkins’ nicknames, figured in parenthesis in the title of a piece Ellington had written especially for the occasion, ‘Self Portrait (of the Bean)’. To my ears, however, the truly memorable performance from this special occasion involved Hawkins soloing at length on a tune that he had probably never recorded previously, a tune with an interesting history that may even have echoes of New Orleans and jazz’s early roots.

‘Mood Indigo’ has two themes or strains and for many years Ellington was listed as the tune’s sole composer. The Duke said he wrote the tune one evening while his mother cooked dinner and that the tune focuses on a little girl who is in love with a boy who walks past her house each day at a certain time. She sits in her window and waits. “Then one day he doesn’t come. ‘Mood Indigo’ tells how she feels.” Barney Bigard, Ellington’s clarinet player in the 1930s, told a different story. Bigard said that he composed the second strain of the tune and that it was based on something his early clarinet teacher from New Orleans, Lorenzo Tio Jr., had written. According to Bigard it was in a recording session on 17th October, 1930, that Ellington “figured out a first strain and I gave him some ideas for it too” and then “we added my second strain and recorded it.” (2) Originally issued as ‘Dreamy Blues’, the tune was soon renamed and became one of Ellington’s early hits and a frequently performed and requested number. When Duke Ellington and His Famous Orchestra began their 1933 tour of England, their first performance was at the London Palladium on Monday, 12th June, and Ellington closed his section of the show with ‘Mood Indigo’. The reviewer for the Melody Maker felt that the Duke’s programme was disappointingly aimed at a variety theatre audience; for those who saw Ellington “as a sponsor of new kind of music… ‘Mood Indigo’ was all they got.” Clearly the tune had already achieved a position of prominence even in England. At Ellington’s first Carnegie Hall Concert in January 1943, which saw the premiere of his suite ‘Black, Brown and Beige’, the evening concluded with ‘Mood Indigo’.

As for Bigard, who was a member of the Famous Orchestra that played at the Palladium, it would take well over twenty years and legal proceedings before he received any royalties for the tune he had helped create. As for Lorenzo Tio, Jr., he died in 1933 and, so far as I am aware, he never received anything.

The lyrics for ‘Mood Indigo’ have always been credited to Irving Mills, Duke’s manager in the 1930s, but in an interview in 1962 Ellington insisted that Mitchell Parish, the lyricist for Hoagy Carmichael’s ‘Star Dust’, actually wrote the words for ‘Mood Indigo’, but, since Parish was under contract to Mills at the time, he never received a dime in royalties for helping the Tio-Bigard-Ellington tune become a standard. Parish himself, in a talk to the Duke Ellington Society of New York, later reaffirmed that he and he alone was the lyricist for ‘Mood Indigo’. I do not think that ‘Mitchell Parish’ has ever replaced ‘Irving Mills’ in any set of credits for the song.

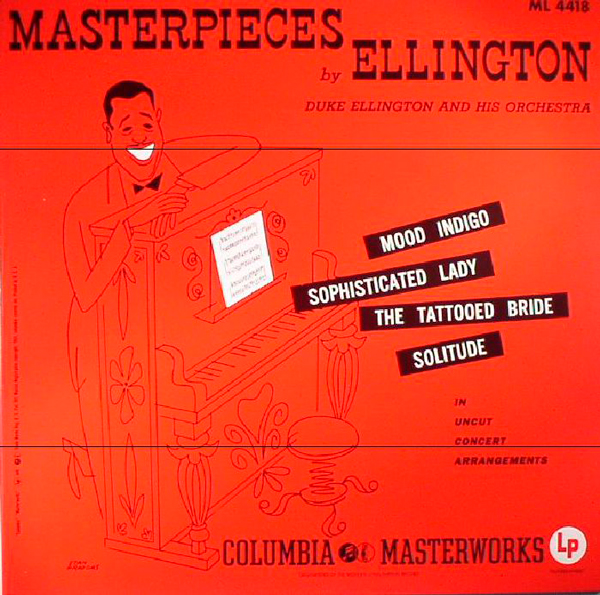

Of all the memorable versions of ‘Mood Indigo’ that Ellington made over the years, one of the most acclaimed is a version from 1950 that lasts a shade over fifteen minutes (3). It was produced by the Ellington Orchestra for the LP ‘Masterpieces by Ellington’ and contained inimitable solos by Russell Procope on clarinet, Johnny Hodges and trombonist Tyree Glenn, using a plunger mute to produce the most vocal of sounds.

On the Ellington/Hawkins album Hawkins would be the only soloist on ‘Mood Indigo’ and the track begins with what knowledgeable listeners will see as an example of the ‘Ellington Effect’. Billy Strayhorn, the Duke’s long-term collaborator, coined the expression ‘Ellington Effect’ in an interview in 1952. The ‘Effect’, in part, comes from the chords selected, how they are voiced and individual tonal colours that Ellington’s chosen musicians bring to their roles. In the 1930 version of ‘Mood Indigo’, Ellington realigns the three main instruments of traditional jazz, clarinet, trumpet and trombone, with the clarinet playing the lowest part. In the extended version from 1950 the opening strain is played by two trombones and Harry Carney on bass clarinet. In preparation for Hawkins’ solo in the 1962 session, Johnny Hodges, Lawrence Brown and Carney again on bass clarinet play the first theme with great delicacy and at a slower tempo than we may have grown accustomed to. Yet all three versions spanning over thirty years ring out as being distinctly Ellingtonian.

Hawkins begins his solo, not with the swagger or the majestic authority we associate with some of his outstanding performances from earlier years, but with restraint, as if the occasion warrants a more respectful approach. Of course, Hawkins still bustles, still explores the chords in a way that leaves few harmonic stones unturned, still seems to have too many ideas for the allotted bars, still sees a space as a vacuum to be filled, but the tone is softer, less full than when the Hawk is on normal power. And the build up in intensity as his solo progresses is very slight and careful. Strong chords from Ellington at the piano start of the third chorus encourage more energy and the fourth chorus has Hawkins flowing with confidence and assurance before he becomes more reflective as Hodges, Brown and Carney return with the first theme and what will be the last chorus. There is a final memorable run from Hawkins just before the end, perhaps to show the speed is still there. Then he bows out gracefully, leaving Ellington with the closing chords. Jimmy Hamilton, Ellington’s clarinettist and tenor saxophonist, who was in the studio at the time, echoed the thoughts of many who were present, “The older he gets, the better he gets.”

Coleman Hawkins

Commenting on Hawkins’ solo, John Chilton writes, “This is one of his finest recorded moments during the 1960s, and it might have been his apotheosis had he not created several phrases of similar rhythmic patterns, but the pros heavily outweigh the cons in Hawk’s one and only recorded rendering of an everlasting jazz theme.” For my part, I wonder whether rhythmic repetition shows not a lack of imagination, but respect for the material at hand, a concern to be restrained rather than free-wheeling. Still, I would agree that this is one of the later Hawkins’ finest performances, a performance whose gentler approach shows a rarely heard facet of a musician who had been on the road since the days of Mamie Smith’s Jazz Hounds.

In 1995 when the original LP was released as a CD some critics were surprised to find a bonus track, another gem from the 1962 recording session. ‘Solitude’, with Ray Nance on violin has Hawkins soloing over two choruses, still not on full power, but with unobtrusive authority and melodic richness. Why this excellent track had been omitted from the original compilation was a question several reviewers raised, doubting whether a suitable musical reason would be forthcoming.

It had taken a long time for them to get together, but Ellington had provided his unique musical embrace and Hawkins had recognised it as a special occasion.

They left the Van Gelder studio in the early evening sunshine. Hawkins had an engagement at the Village Gate awaiting him. Ellington would soon be leaving New York for engagements elsewhere.

“After four hundred years, we finally made it!” Hawkins observed.

“You don’t think it was too soon?” the Duke inquired.

Peter Gardner

March, 2018

Acknowledgements

I am most grateful to Steve Marshall from Marshall McGurk, Crosby, Maryport, Cumbria, and to Sam Gregory, Dawkes’ woodwind specialist.

Endnotes

(1) The CD ‘Duke Ellington Meets Coleman Hawkins’, Impulse IMP 11622 has all the tracks from the original LP recorded on 18th August, 1962, plus the version of ‘Solitude’ that I mention later.

(2) ‘Mood Indigo’ from October, 1930 is available on: Duke Ellington, ‘Cotton Club Stomp’, Classic Recordings, 1927-1931, Naxos Jazz Legends 8.120509. It will also be found in other compilations.

(3) The CD Duke Ellington ‘Masterpieces by Ellington’, Columbia/Legacy 512918 has all the tracks from the original LP plus some bonus tracks.

Some sources used

Barney Bigard, With Louis and the Duke (Oxford University Press, New York, 1986).

John Chilton, The Song of the Hawk (Quartet Books, London, 1990).

Stanley Dance, Original Liner Notes from the LP ‘Duke Ellington Meets Coleman Hawkins’, Impulse! AS – 26, 1963.

Ted Gioia, Jazz Standards (Oxford University Press, New York, 2012).

Derek Jewell, Duke: A Portrait of Duke Ellington (Elm Tree Books, London, 1977).

Ben Tucker, ed., The Duke Ellington Reader (Oxford University Press, New York, 1993).