The First Great Jazz Saxophonist

3rd November 2017“Sidney Bechet was, by an impressive margin of several years, the first great jazz saxophonist.”

– Humphrey Lyttelton

One day in 1920 a trumpeter in his very early twenties and a clarinettist, who may not have been much older, were walking down London’s Wardour Street. The trumpeter had been born in the West Indies, but had spent most of his early years in South Carolina. The clarinettist, who had toured with various groups since a teenager, was originally from New Orleans. He was a Creole; most of his forbears were African Americans, but at least one was French. Both the trumpeter and the clarinettist had come to England from America with Will Marion Cook’s Southern Syncopated Orchestra in 1919. In the window of J. R. Lafleur’s music shop at 147 Wardour Street the clarinettist spotted a shiny straight soprano saxophone.

He had played on some saxophones, including a curved soprano, back in America, though he had never been attracted to them. But he was delighted when he tried the straight soprano in Lafleur’s shop; he and the soprano were a marriage made in heaven. The young West Indian trumpeter, who spent much of his future career in Europe, survived Nazi imprisonment and became a professor of music in France, was Arthur Briggs. The clarinettist, who would eventually concentrate on the straight soprano, would become a jazz legend. He was Sidney Bechet, the father of the soprano saxophone in jazz and the first great jazz saxophonist. Yet, for all his brilliance, it was only in the final decade of his career that he achieved the stardom and public acclaim his talent deserved, and his adoring public resided not in the country of his birth, but in France.

When he applied for his first passport, Bechet gave his date of birth as 14th May, 1897, but some think he must have been born earlier because he was a well established and respected musician and feared musical opponent on both clarinet and cornet in New Orleans by the start of the First World War. Those Bechet claimed to have heard and those he played with in his early years are some of the most important figures in jazz’s birth and infancy: he said he heard Buddy Bolden play; he saw the young Louis Armstrong’s vocal quartet singing on street corners; and he played with Bunk Johnson, Freddie Keppard, Kid Ory and Joe ‘King’ Oliver. By 1916, though some accounts give an earlier date, he was touring vaudeville theatres playing clarinet. When Bechet was in Chicago, he was spotted by bandleader Will Marion Cook and in June 1919 Bechet sailed for England with Cook’s Southern Syncopated Orchestra.

Jazz historians see the 1920s as one of the most important decades in the entire history of the music. It was an era when geniuses like Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington emerged, when definitive recordings were made and reputations were established by musicians who, in the main, were playing in Chicago or New York. As for Bechet, he spent most of the 1920s in Europe. His trip to England with Marion Cook ended when he returned to America in November 1922, but by September 1925 he was on his travels again. This time he was off to Paris with La Revue Negre, the show that would make a star of the young Josephine Baker. The Revue later moved to Belgium and Germany, where Bechet joined up with a group of musicians who were on their way to Moscow. It wasn’t until December 1930 that Bechet arrived back in America, by which time Wall Street had crashed and the jazz age and the great recording period of the 1920s were over.

So, had Bechet missed out? Well, although he was only in America for less than three years in the 1920s that brief period was crammed full of activity: he toured with ‘The Empress of the Blues’, Bessie Smith, he taught the young Johnny Hodges (Hodges would later remark that if it hadn’t been for Bechet “I’d probably just be playing for a hobby”), he toured as ‘The Wizard of the Clarinet’ with Marion Cook, he opened a night club, he joined the fledgling Duke Ellington band and he recorded. Frequently these recordings were with groups organised by pianist, composer and music publisher, Clarence Williams. Bechet made his first recordings in America with Clarence Williams’ Blue Five on 30th July, 1923. Of the two tracks recorded on that day, Fats Waller’s ‘Wild Cat Blues’, actually a rag rather than a blues, is a masterful demonstration of saxophone playing. Whatever difficulties the soprano saxophone poses, and some musicians never seem to tire of expanding on them, they didn’t thwart Bechet; on ‘Wild Cat Blues’ he swoops, growls and plays all over the horn with passion and power, and, as was often the case on Bechet’s recordings, the accompanying musicians are simply that.

One instrumentalist that Bechet couldn’t force into the background was a young cornet player who, as a street singer in New Orleans, had been thrilled to march behind the bands Bechet played in. He was someone who had recently left Joe ‘King’ Oliver’s band in Chicago, who was taking New York by storm and would soon take jazz by storm. He was Louis Armstrong. Bechet and Armstrong were part of the Clarence Williams’ Blue Five that met to record on 8th January, 1925. Apparently Williams intended the recording session to showcase the talents of his wife, the singer Eva Taylor. For Bechet’s biographer, John Chilton, when it came to the recording of ‘Cake Walking Babies from Home’, Eva Taylor’s vocal was incidental, for the track was a “Duel of the Giants”, a “ferocious” pairing of Bechet and Armstrong, resulting “in a dead heat”.

If Bechet couldn’t get the better of Armstrong, he certainly seems to have put the great tenor saxophonist, Coleman Hawkins, firmly in his place. The story goes that Hawkins, a cocky young star of the Fletcher Henderson orchestra, had cast aspersions on the abilities of musicians from New Orleans and Bechet, in defence of his fellow New Orleanians, challenged Hawk to a musical duel. Guitarist Danny Barker recalled the event: “So the date was set, and the two reed giants met at the over-crowded Band Box (Club in New York). Bechet blowing like a hurricane embarrassed the Hawk, he played and continued to play as Hawkins packed his horn and as he walked out angrily Bechet followed him outside and woke up the neighbourhood.” That’s what you call cutting someone. Bechet was always a competitor and with the power of the soprano saxophone he could dominate most instrumentalists and, at times, whole ensembles.

By the autumn of 1925 Bechet would be back in Europe. When he returned to America in 1930, despite the greatness of his recordings with Clarence Williams and Armstrong, he was, as one of his famous students, Bob Wilber observed, “a forgotten figure”. Soon Bechet turned his attention to running a tailoring shop in Harlem, though that wasn’t a great success, and for a while he toured with Noble Sissle’s band, at times billed as Noble Sissle’s Society Orchestra, without any great acclaim. Fortunately revivalism or what some called New Orleans revivalism brought a change for the better.

The revivalist movement in jazz had various strands: it began in the late 1930s with young musicians in America trying to recreate the music of ‘King’ Oliver, Jelly Roll Morton and Armstrong’s Hot Fives and Sevens; it involved the discovery (or rediscovery) of earlier players, like Ory and Bunk Johnson, who had given up the business, and of those New Orleans musicians who hadn’t gone up North; it resulted in renewed attention being paid to musicians from the 1920s who were still active; and in the 1940s it spread to this country and the continent. Amazingly, at the very time that Parker and Gillespie were attracting one group of jazz fans to supercharged bebop, legions of revivalist banjoists were trying to strum like Johnny St. Cyr and cohorts of revivalist clarinet players were struggling with ‘High Society’.

Renewed attention brought more recording opportunities and two recordings from the start of the revivalist period have always been particular favourites of mine and of many of Bechet’s followers. Victor Herbert’s tune ‘Indian Summer’ dates from 1919, but it had new life breathed into it when, in 1939, Al Dubin wrote some lyrics for Herbert’s melody and helped it on its way to becoming a standard. Bechet recorded the tune in February 1940. ‘Passionate’ and ‘delectable’ are two of the terms that have been used to describe his performance. A little over one month later Bechet was recording for America’s Hot Record Society with a group billed as ‘The Bechet-Spanier Big Four’. The quartet featured Tommy Dorsey’s guitarist, Carmen Mastren, who would later come to England with Glenn Miller, ex-Ellingtonian, Wellman Braud, on bass, Muggsy Spanier on cornet and Bechet. All of the nine sides the Big-Four recorded are outstanding, but I have always felt that none betters the first take of ‘China Boy’, where Spanier, bravely, holds on to the lead, while Bechet on soprano plays all round him(1). This is a masterpiece.

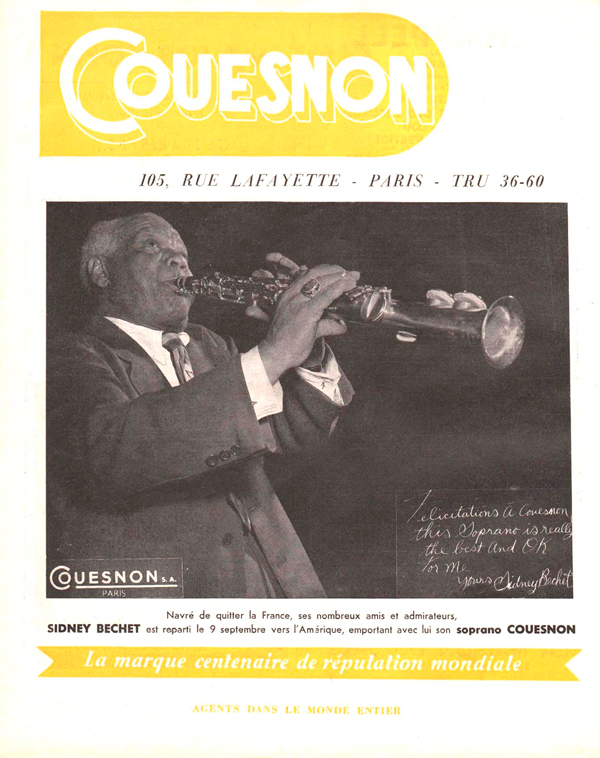

In May 1949 Bechet returned to Europe appearing at the Paris International Jazz Festival where he was so enthusiastically received that future trips were planned and in 1951 Bechet settled in France permanently. In America, though known to revivalists and the jazz cognoscenti, he was not a public figure. In France, while seen as a living legend by jazz fans, he was also someone whose moving melodies and infectious swing touched the hearts and feet of those with no knowledge of jazz or its history and no inclination to acquire such knowledge. And, being a Creole, his move to France had elements of a homecoming.

In the words of Tom Perchard, historian of post-war European jazz, in France Bechet was “a star: in Paris he worked in the booming basement clubs (or caves), but he also toured the country appearing in concert and on mixed music hall bills. The breadth of the audience he cultivated meant that his most famous record, 1949’s “Les Oignons”, would sell over a million copies in the 1950s. In 1955, 3,000 people, mainly teenagers, crammed into Paris’ Olympia to hear Bechet play; the same number, outside and unable to gain entry, started a riot instead” (2). At the time jazz critic, Andre Hodier, spoke of Bechet pulling off “the miracle of enthralling at once the jazz fan, the musician and the uninitiated listener”, while a modern writer, Andy Fry, fondly reminds us that in France during the 1950s “paunchy, grey-haired Bechet became a national celebrity.”

Philip Larkin’s poem ‘For Sidney Bechet’ begins:

That note you hold, narrowing and rising, shakes

Like New Orleans reflected in the water.

To modern saxophonists, however, whether they listen to Bechet’s early recordings or those from the revivalist period made in America or the later ones made in France, it is Bechet’s shaking, his heavy vibrato that they may find unsettling. If a defence is appropriate here, it could be pointed out that in his early years Bechet listened to recordings by opera stars, and the vibratos of opera singers from those times would no doubt be regarded as over-the-top by to-day’s opera lovers. Vibratos, like divas, have slimmed over the years. But let’s avoid being defensive. Bechet’s tone was an important facet of a passionate musician. He was forceful, eloquent and moving with (I am tempted to say because of) the sound that he produced; he would have been weaker, more reserved and colder with a lesser tone. As Bob Wilber knowingly observed, “Bechet was never one to play ‘background music’.”

Bechet died from cancer on 14th May, 1959, in Garches, near Paris, on what many took to be his sixty-second birthday. Professor Arthur Briggs, who, nearly forty years earlier, had walked down Wardour Street with the young clarinettist, was one of thousands of mourners at the funeral. Much has since been written about Bechet’s playing, his passion, his lyricism, his awesome command of the blues, his swing and his vitality, but I hope a succinct and revealing assessment from one the greatest of musical authorities will provide a suitable conclusion to this short essay. Duke Ellington said, “Bechet to me was the very epitome of jazz.”

Peter Gardner

September, 2017

Acknowledgements

I am grateful for the help of Steve Marshall from Marshall McGurk, Maryport, Cumbria, and Dawkes’ woodwind specialist, Sam Gregory.

Endnotes

(1) Bechet’s early recordings can be found in various collections. The four recordings I have mentioned (‘Wild Cat Blues’, 1923, ‘Cake Walking Babies from Home’, 1925, ‘Indian Summer’, 1940, and ‘China Boy’, 1940) can all be found in the 4 CD set ‘The Sidney Bechet Story’, Proper Box 18. Used copies of this superb boxed set are still available for low prices.

(2) ‘Les Oignons’ together with many other tracks recorded by Bechet in France with Claude Luter’s band between 1949 and 1951 can be found on the competitively priced Avid Jazz double CD ‘Sidney Bechet, Four Classic Albums’, AMSC 1189.

Some sources used

Sidney Bechet, Treat it Gentle (Cassell, London, 1960).

John Chilton, Sidney Bechet: The Wizard of Jazz (Macmillan, Basingstoke, 1987).

Andy Fry, ‘Remembrance of Jazz Past: Sidney Bechet in France’, in J. F. Fulcher (Ed.) The Oxford Handbook of the New Cultural History of Music (Oxford University Press, New York, 2011).

Philip Larkin, The Whitsun Weddings (Faber and Faber, London, 1964).

Humphrey Lyttelton, The Best of Jazz: Basin Street to Harlem (Penguin, Harmondsworth, 1980).

Tom Perchard, After Django: Making Jazz in Postwar France (University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, 2015).

Bob Wilber notes for the 3 CD set ‘Sidney Bechet’, Mosaic Select 22 (MS-022), 2006.