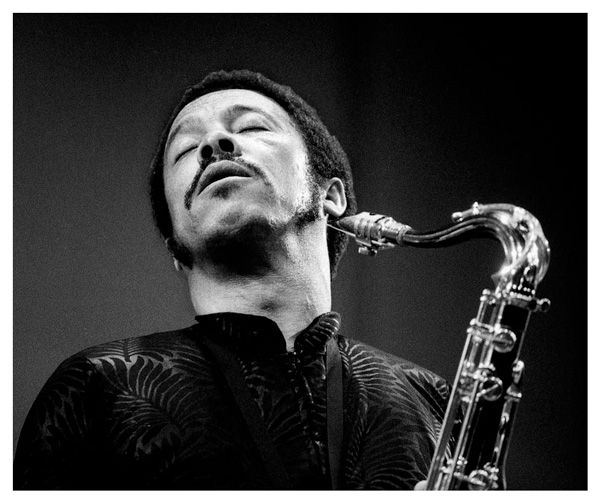

The Fastest Tenor in the West

17th January 2018He was a seventeen year-old alto saxophone player when he first joined Lionel Hampton’s band in 1945, but Gladys Hampton, Lionel’s wife, who also managed Lionel’s band, insisted that the teenager with the alto had been hired to play tenor saxophone, and no one argued with Gladys. So, Johnny Griffin started to play tenor. Before too long he was duetting with the band’s star tenor player, Arnett Cobb. Eventually the routine of playing Hampton’s big hits night after night became tiresome. Griffin left Hampton’s band, and, though he returned for a brief spell, he finally quit for good shortly after his nineteenth birthday.

Inspired by Charlie Parker (“the greatest messenger” is how Griffin described Parker), nevertheless the young tenor player was determined to be his own man. “I wanted to be original, so I was afraid to hang out with saxophone players” is what he told interviewer Art Taylor. Instead, after leaving Hampton, Griffin began to pick the brains of some of the greatest pianists in modern jazz. “I learned my lessons from Bud Powell, Elmo Hope and Thelonius Monk. I walked the streets with them in the forties.”

Drafted into the United States Army in 1951, Griffin did his basic training in Hawaii, where a vacancy arose in his army station’s band, not for a tenor sax player, but for an oboist. Fortunately, Griffin had studied the oboe in high school. Rather than being posted to Korea, where a great many of his military friends would lose their lives in the ongoing conflict, Griffin remained in Hawaii, oboist with the 264th Army Band. Chapter Five of Mike Hennessey’s fine biography of Griffin deals with this period of the saxophonist’s life. The chapter’s title is ‘The Life-Saving Oboe’ (1).

Griffin left the Army in 1953, and by the time he came to record his first Blue Note album in April, 1956, just a few days before his twenty-eighth birthday, the one-time altoist and oboist was an experienced, knowledgeable and technically brilliant tenor player. He had tried to master what he saw as Don Byas’ “fluidity”, he had played alongside Wardell Gray and Dexter Gordon, he had held his own in duels with the formidable Sonny Stitt (Griffin would later recall, “with Stitt it was a pitched battle from the word go”) and he was viewed with awe and trepidation by saxophonists on the thriving Chicago jazz scene.

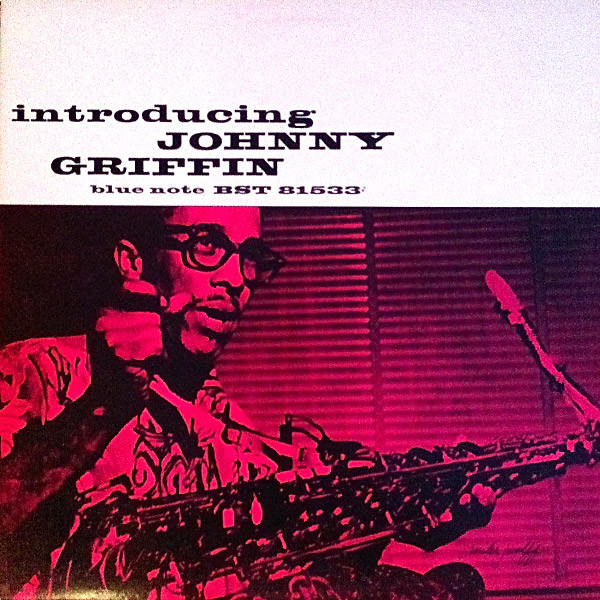

Introducing Johnny Griffin LP

On ‘Introducing Johnny Griffin’, Griffin’s first LP for Blue Note, the tenor player is accompanied by an outstanding rhythm section: Wynton Kelly, piano, Curly Russell, bass, and Max Roach, drums. The album opens with a Griffin original, ‘Mil Dew’, but if you think this is miraculous, try a later track, Cole Porter’s ‘It’s Alright with Me’. Whenever I hear Griffin with his wondrous amalgam of speed, precision, swing and passion, I am reminded of Ross Russell’s appraisal of Parker’s devastating performance in November 1945 on ‘Ko Ko’: “a piece of reckless and astonishing virtuosity…saxophone playing to end saxophone playing – to castrate all other saxophonists.”

When ‘Introducing Johnny Griffin’ was later released on CD (2) two bonus tracks from the original session were added, Jerome Kern’s ‘The Way You Look Tonight’ and Ray Noble’s ‘Cherokee’. Both are storming performances. In his notes for the CD release Bob Blumenthal jokes that one reason these additional tracks might have been omitted originally was out of mercy to contemporary saxophonists. Blumenthal’s piece of humour has an interesting rider: it is claimed that when Tubby Hayes first heard Griffin at Ronnie Scott’s Club, he was seriously distressed and had to be consoled by fellow musicians who tried to convince Britain’s fastest tenor that speed wasn’t everything.

But there was much more to Griffin than speed. He had a rich, warm sound with a very noticeable vibrato, particularly on ballads. ‘These Foolish Things’ and ‘Lover Man’ are the two slow ballads on ‘Introducing Johnny Griffin’ and on both he begins by showing considerable respect for the melody. He definitely had a softer side. And he had a great sense of humour; quotes often make quite incongruous appearances in Griffin’s solos, few sounding as odd as the extract from ‘We Wish You a Merry Christmas’ that serves as a coda to ‘These Foolish Things’. Griffin also sighed, moaned or grunted approval after particularly memorable phrases. He enjoyed soloing and enjoyed communicating with an audience. The poet and jazz critic, Philip Larkin, once confided, “I have a weakness for the entertainers of jazz (as opposed to more sombre characters who suggest by their demeanour that I am lucky to hear them).”

Johnny Griffin, John Coltrane and Hank Mobley

Griffin, most definitely, was not a moody, back-to-the-audience, sombre performer. He was one of jazz’s entertainers, and on his first album for Blue Note, while he struck fear into fellow saxophonists, Griffin seems to have enjoyed himself enormously demonstrating hard bop at its exhilarating and joyous best. It is easy to see why someone like Griffin, who prioritised red-blooded explorations of the fabric of songs, despised both the cool detachment often associated with America’s West Coast and the unstructured meanderings of jazz’s avant-garde.

Soon, as other albums followed, including ‘Congregation’ with Sonny Clark on piano (3) and ‘Johnny Griffin Sextet’ for Riverside Records, Griffin, a small man with an outstanding talent, was being billed as ‘The Little Giant’ and ‘The Fastest Tenor in the West’, and there followed spells in groups led by two of jazz’s most inspirational musicians, Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers and the Thelonius Monk Quartet. The next group Griffin was involved with featured the fearsome two-tenor pairing of himself and Eddie ‘Lockjaw’ Davis, who, a few years earlier, had been one of the star soloists with Count Basie. ‘Tough Tenors’, ‘Griff and Lock’, ‘The Tenor Scene’ and ‘Blues Up and Down’ were just some of the albums recorded by the Eddie ‘Lockjaw’ Davis and Johnny Griffin Quintet at the start of the 1960s (4). If you like your jazz to have airs of gentility and to be smooth and delicately unobtrusive, the music of ‘Jaws’ and Griff is not for you. The two tough tenors play jazz with lumps in it. Reviewing ‘Tough Tenors’ in Down Beat, Gene Lees spoke of the music as “booting, belting jazz” with the two leaders “producing a big, gutsy sound that is all virility and a yard wide.” Yet, as more than one critic noted, with Griffin and Davis there was never the wild excesses of ego-driven cutting contests or the frantic indulgencies of Jazz at the Philharmonic conflicts; they were just two friends who inspired each other to great things.

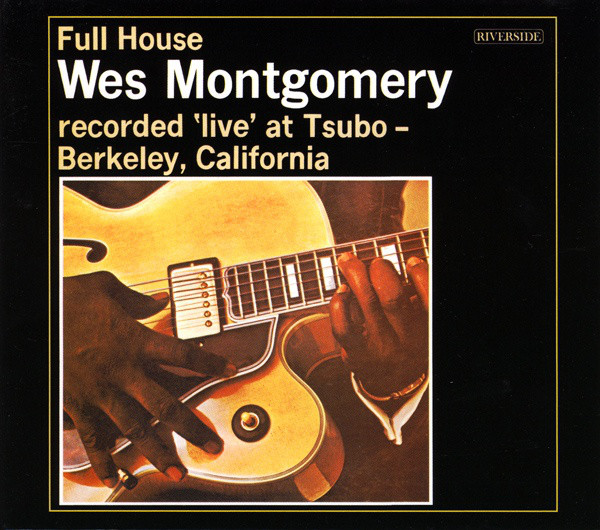

Wes Montgomery Full House LP

Unfortunately the two tenor quintet only lasted as a regular working group until the summer of 1962. Poorly paid engagements and the rise of free jazz are often cited as reasons for the group’s demise. About the time the group with ‘Lockjaw’ was folding, Griffin had the opportunity to record a live album with the master of the electric guitar, Wes Montgomery, accompanied by Miles Davis’ current rhythm section, Wynton Kelly, piano, Paul Chambers, bass, and Jimmy Cobb, drums. The all-star group got together on 25th June, 1962, at the Tsubo coffee house, in Berkeley, California, in front of a packed house and produced an album, ‘Full House’ (5), that many still consider to be one of Montgomery’s best and on which Griffin is superb throughout. Alas, such gigs were few and far between and Griffin was grateful when a three month tour of Europe was arranged that started in Paris in December 1962, a city which, at the time, was home to Kenny Clark, Kenny Drew, Chet Baker, Sonny Criss, Bud Powell, Hazel Scott and many other American jazz stars.

In Europe Griffin was welcomed by fans who knew his music, he was respected, he was well paid and he learnt to slow down, except, of course, when blowing. This was quite a contrast to scuffling in America in conditions he once described as “deplorable”. Griffin returned to America in March 1963 to a marriage that was collapsing, to demands from the Inland Revenue Service for thousands of dollars of back taxes and to fewer venues for his kind of music. In May 1963, as Don Byas and Sidney Bechet had done and as Ben Webster soon would do, Griffin moved to Europe to stay. For several years he lived in Paris, where he remarried, then he moved to Bergambacht in Holland and in the early 1980s he lived in Roquefort-les-Pins on the Cote d’Azur. And wherever he lived he would leave frequently to play in clubs, festivals, concert halls, to record, to appear with reunion groups and to play with big bands (for a few years he was one of the stars with the widely acclaimed Kenny Clarke-Francy Boland Big Band (6)). He also made the occasional trip back to America. One tour of America in 1978 included an appearance at Carnegie Hall, where his solos were greeted with standing ovations, but it was in Europe that he felt at home. “Life in Europe has really worked out beautifully”, he said in an interview in 1979. “It has been an enriching experience and, apart from one or two lean moments, there has always been plenty of work.”

For many of his former associates in America, things did not work out so well. As a rule the jazz life takes a heavy toll on its musicians. Those Griffin played and recorded with before his move to France were not exceptions. Sonny Clark died in 1963 aged just thirty-two, Paul Chambers died in 1969 aged thirty-three, Wynton Kelly passed away aged forty in 1971, Elmo Hope was only forty-three when he died in 1967 and Wes Montgomery was forty-five when he died in June, 1968. Europhile Griffin was much more fortunate.

In 1984, well into his fifties, Johnny Griffin and his wife, Miriam, left the Cote d’Azur and, as Mike Hennessey describes it, moved into their new large home, a chateau, Chateau Bellevue, which stood in many acres of farm land near Availles-Limouzine, a small village in the west of France, some two-hundred and fifty miles from Paris. From his new base Griffin continued to be as musically active as ever.

On Saturday, 26th July, 2008, The New York Times reported: “Johnny Griffin, a tenor saxophonist from Chicago whose speed, control and harmonic acuity made him one of the most talented musicians of his generation yet who spent most of his career in Europe, died Friday at his home in Availles-Limouzine…He was 80 and had lived there for 24 years…He played his last concert on Monday in Hyeres, France.”

“Sometimes”, said Griffin, “when the rhythm section is really cooking and everybody is together, this feeling of euphoria comes over you. Sometimes I have to stop and laugh and I say, ‘My God – and I’m getting paid for this, too!’” The Little Giant loved his music and his audiences and it showed.

Peter Gardner

January, 2018.

Acknowledgements

I am most grateful for the help of Sam Gregory, Dawkes’ woodwind specialist, Steve Marshall, Marshall McGurk, Maryport, CA15 6SH and David Nathan, Jazz Archivist, National Jazz Archive, Loughton Central Library, Trapps Hill, Loughton, IG10 1HD.

Endnotes

(1) As I was starting my research into Johnny Griffin, I found out that Mike Hennessey, one-time editor of Billboard and greatly respected authority and writer on jazz and popular music (He wrote biographies of both Griffin and Kenny Clarke) had sadly died at the age of 89 in August, 2017.

(2) ‘Introducing Johnny Griffin’, with bonus tracks, was issued on Blue Note CD 74218.

(3) ‘The Congregation’, with a bonus track, was issued on Blue Note CD 89383. Both ‘Introducing Johnny Griffin’ and ‘The Congregation’, but without bonus tracks, have been issued on the competitively priced 2 CD set: Johnny Griffin ‘Four Classic Albums’, Avid Jazz AMSC 1266. This 2 CD set also contains the 1957 album ‘A Blowing Session’ which features Griffin and fellow tenor players Hank Mobley and John Coltrane. I would strongly recommend this Avid 2 CD set.

(4) ‘Tough Tenors’, ‘Griff and Lock’, ‘The Tenor Scene’ and ‘Blues Up and Down’ plus other albums by the Davis/Griffin quintet are on the 4 CD set: Eddie ‘Lockjaw’ Davis/Johnny Griffin Quintet ‘The Complete Sessions’, Jazz Dynamics 001. (‘Complete’ here is qualified. The Jazz Dynamics set is said to include all the recordings by the quintet with Junior Mance, piano, Larry Gales, bass, and Ben Riley, drums. The frontline of Davis and Griffin did record with other rhythm sections.)

(5) Wes Montgomery ‘Full House’, with bonus tracks, was issued on the Original Jazz Classics CD OJCCD 106-2.

(6) Two recommended CDs by the Clarke-Boland Big Band, both of which feature Griffin, are: ‘The Complete Live Recordings at Ronnie Scott’s, February 1969’, Rearward RW 138; and ‘Two Originals: All Blues/Sax No End’, MPS 523 525-2.

Some sources used

Bob Blumenthal, notes for ‘Introducing Johnny Griffin’, Blue Note RVG Edition 74218, 2006.

Mike Hennessy, ‘Johnny Griffin and the Jazz Life Force’, Jazz Journal International, May 1979, pp. 13-14.

Mike Hennessey, The Little Giant: The story of Johnny Griffin (Northway, London, 2008).

Max Jones, Talking Jazz (Macmillan, Basingstoke, 1987).

David H. Rosenthal, Hard Bop: Jazz and Black Music 1955-1965 (Oxford University Press, 1992).

Art Taylor, Notes and Tones: Musician to Musician Interviews (Da Capo, New York, 1993).